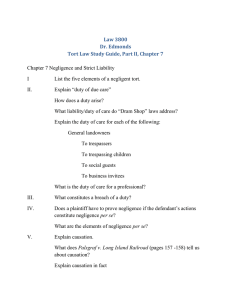

Torts Outline Draft Intentional Torts A. Introduction

advertisement