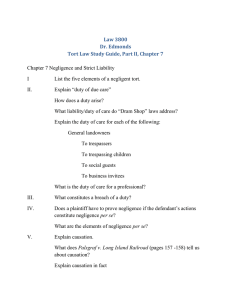

What is a tort? TORTS OUTLINE

advertisement