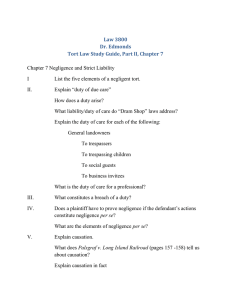

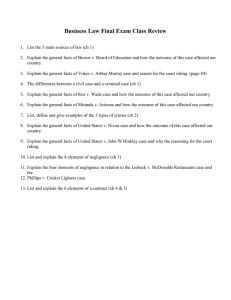

Torts Outline: Intentional Torts, Negligence, Strict Liability

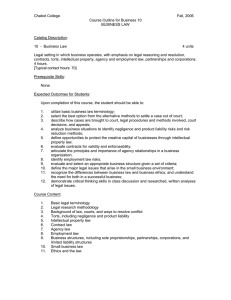

advertisement