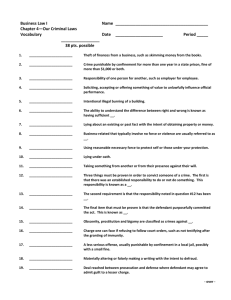

Criminal Law Fall 2005 Kim Taylor-Thompson

advertisement