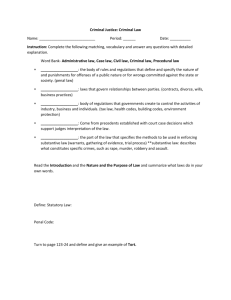

Source of Criminal Law Criminal Law—Outline

advertisement