Who/What is God?

advertisement

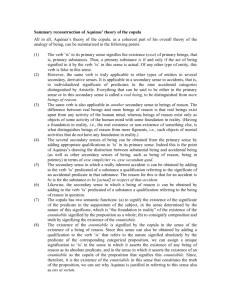

Who or What is God? Vishnu Buddha Contemplating God Jesus Christ “He (Allah) Knows Everything” Primitive Mother Parvati – young lover Virgin Mary Kali – wrathful goddess The Limits of Imagry Nanak, First Sikh Guru (15th – 16th Century C.E.) On a visit to Mecca, Nanak was waked from sleep by his Muslim hosts and admonished not to lie down with his feet toward God. He responded, “Try to point my feet where God is not, as God is everywhere.” Traditional and Philosophical Notions of God God Beyond Images • • • • Personal or Impersonal? Separate from, or part of, reality? With, or without, limits? Like, or unlike, we humans? • Comprehensible or incomprehensible? Our Knowledge of God Revealed Theology • Passively received Natural Theology • Actively constructed • Prophetic utterances • Experience and observation • Sacred literature • Rational inferences • In principle, doctrines are absolute • By rules of logic, conclusions are probable Avicenna – Necessary Being Essential elements of the main argument are pretty straight-forward: Main Premise: All beings cannot be contingent – they can’t all be “caused and conditioned.” Conclusion: a necessary being must exist – this is what we call God. Reconciling this conclusion with more traditional conceptions of God’s essential properties is more difficult! God as Emptiness Cobb introduces a new consideration: God is often considered a being “without limits” – the literal meaning of “infinite” Every property is a limit, in (at least) the sense that the predication of a property entails the negation of any other incompatible properties. His conclusion: that God has no positive properties, or is more accurately characterized as “Emptiness” – that reality which, because it has no nature or properties itself, allows all other beings to be. Glossary - AVicenna Essential Concepts and Their Use in the Readings Contingent and Necessary Being Contingent: having the property of being caused by another; of existing only under specific conditions Necessary: having the property of being uncaused; of having to exist by virtue of a being’s nature Application in Avicenna’s “The Nature of God” The necessary being is derived from the contingent beings of the universe, as the “place” where the causal chain of creation must have started. By definition, contingent beings did not at one time exist; a previously existing being or power is the condition of a contingent being’s existence. Without a necessary being – which by definition does not depend on a previously existing being or power for its existence – there would be no beginning of the causal events which ultimately created the universe as we know it. Essential and Accidental Properties Property: a quality or trait belonging to a being. Often said to “be predicated of” a being, by virtue of the subject-predicate relation. Example: “Greatness can be predicated of God” = “God is great” Essential Property: a quality or trait which makes a being the kind of being that it is; a quality or set of qualities that define a category of beings Example: “Mammals give birth to their offspring.” Accidental Property: a quality or trait which is possessed by a being, but is not essential to that being; a potentially mutable quality of a being Example: “A college education can take 5 years to complete.” Essential and Accidental Properties - Applications Avicenna is concerned with showing two things: 1. that God – a necessary being – cannot have accidental properties, and 2. that God cannot change – God is perfect and complete 1. All the properties of a necessary being are one with its very nature (including its existence, Avicenna argues). That is, all its properties are essential properties, and these are all completely unified. Therefore, they cannot be either acquired or lost. But accidental properties can be acquired and lost. Such properties, therefore, cannot be predicated of a necessary being. 2. Obviously, if no properties of a being can change, that being will be what it is, as it is, for the entire span of its existence. In the case of a necessary being, existence is eternal if a being is necessary. This line of thinking adds the observation that existence cannot be an “accidental” property, as all accidental properties can change. Quiddity and Reality Quiddity: the essence or “whatness” of a being; the sum total of the properties that make a being “what it is” Reality: the existence or actual being of a being; its ontological actuality or factuality Application in Avicenna’s “The Nature of God” To have reality, contingent beings depend on other beings or powers. Thus, what they are – their quiddity - can be distinguished in fact as well as in principle from their reality, or their actual existence. Example: the nature of a table “exists” in the carpenter’s mind before it actually exists in reality (after s/he has made the table) According to Avicenna, a being that is necessary has a nature or quiddity, but if this being is uncaused (if it is not dependent on a prior existing being for it’s reality), then there was not a time in which it did not exist. It’s nature can’t be distinguished from its reality. The Four Kinds of Causes Active Cause: that power or activity which actually brings something into existence. Examples: the physical labor of the carpenter as s/he creates the table; the physical processes governing the development of the fetus into a human being. Material Cause: the “stuff” out of which a being is made. Examples: the oak from which the table was made; the protein-based materials out of which a human being is made Formal Cause: the kind of thing which is being made or caused to exist. Examples: a table, rather than a house or a sculpture; a human being, rather than a dolphin or a cat (note: the material cause can accommodate many different formal causes) Final Cause: the function a thing performs in its environment; the purpose for which a thing was created Examples: to have a place for eating, working on papers, etc; ?, deciding the purpose of human existence would involve us in the meaning of life, which is certainly up for debate. The Four Kinds of Causes - Application With respect to contingent beings, the various causes can really exist independently of each other (with the possible exception of the formal and final causes). Example: the carpenter thinks about the table without having either the materials or the tools to bring the table into existence. Avicenna claims that in whatever way we think of how God could be (i.e., no matter which kind of cause we consider), we cannot think of any of the various causes existing without the others. Consider: If all the properties of God are necessary, none can be either created or destroyed. If these properties define God’s nature, then His nature can be neither created nor destroyed. This means that the set of properties, and therefore the being described by these properties, can be neither created nor destroyed. Glossary - Cobb Essential Concepts and Their Use in the Readings Metaphysical Dualism Metaphysics: the theory of reality; the area of philosophy which attempts to distinguish the real from appearance, or from the illusory Dualism: from “dual,” or “two,” the view that there are two distinct substances out of which the entire universe is created. Typically, the two are characterized as matter and spirit. Application in Cobb’s “Emptiness and God” Metaphysical dualism creates an unacceptable and unhelpful conceptual tension in the concept of God, which suggests that a different metaphysics is worth considering. If God is purely spiritual, God cannot be a father, king or any other person whose role is modeled on the secular world and whose role is therefore incompatible with other roles (mother, servant). If God is purely physical, God is not worthy of worship Emptiness In a dualistic ontology: • being and non-being are incompatible states of reality. Example: there is sound, or there is silence (the absence of sound); one has goodness, or one doesn’t; and so forth. • non-being cannot be described, experienced or coherently discussed. In a Buddhist ontology: • Non-being is as real as being; both are aspects of ultimate reality. Example: without silence (for example: pauses between sounds in spoken communication, empty spaces between physical marks in written communication), there would be no comprehended speech. • Ultimate reality can therefore have no properties Rationale: the possession of any property logically excludes the possession of a conflicting property. If ultimate reality is the source of all beings (thus, all properties), ultimate reality must have no nature itself. Religious Problem with Emptiness If God, as “ultimate reality,” is in fact the ground of all other beings, then “God” has no defined properties, including those which traditionally define God as good, or just, or even all knowing. This would suggest that God is “himself” beyond not just all properties, but also all dualisms – good and bad, just and unjust, etc. This God is not a god of either worship or moral guidance. But religions have also long promoted the idea that there is a “right way” for us to act and in fact for the universe to be. “Emptiness” is not an idea which can accommodate this judgmental or discriminating approach to reality. The Ultimate of Rightness According to Cobb, Christianity understands and prioritizes this “rightness” This priority tends to anthropomorphize our concept of God. Doing so is unacceptable, because God can’t just be one more being among other beings. However, this priority also tends to engage our intuitions that there are things that are more rather than less important; more rather than less desirable; right rather than wrong. Cobb concludes that there is another ultimate besides that of the ineffable, indescribable Emptiness of Being: This is the ultimate of rightness, through which we experience a transhuman domain of goodness and of development from the worse toward the better. A New Concept of God Cobb is thus trying to integrate two distinct but venerable traditions in world religions: 1. Mysticism: God is the ultimate ineffable reality Metaphysics: God, to be the ground of all beings, cannot have properties of his own 2. Morality: God desires and acts to achieve goodness in the universe. Cobb does not achieve this goal of integration. He does, however, ask us to consider thinking of the ultimate in non-personal ways, and in ways that will incorporate as much of world religions as is reasonable.