Vol. 23 No. 2 December, 2012 Editor: Jennifer Berry, Research Professional III

advertisement

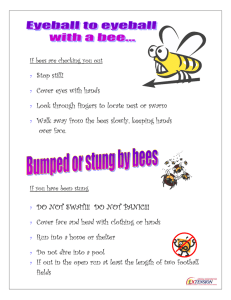

Vol. 23 No. 2 December, 2012 Editor: Jennifer Berry, Research Professional III University of Georgia Bee Lab Promotes Importance of Pollinators and Beneficials at Sunbelt Ag Expo Show Ben Rouse and Nicholas Weaver standing ready at the Sunbelt Expo! This past October, staff from the UGA bee lab traveled south to Moultrie, Georgia to participate in the Sunbelt Ag Expo Show, which, for thirty-five years, has showcased the newest innovations in agriculture. The annual Expo is housed on a 100-acre site and features over 1,200 exhibitors. Alongside every kind of agricultural equipment imaginable, research specialists from the College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences (CAES) offered helpful, educational information to the public. The college’s theme this year was “Pollinators and Peanuts,” which provided the perfect opportunity to launch our “Protecting Pollinators and Beneficials” program in our exhibit. Here at the UGA Bee Lab, one of our most important goals is to disseminate information about all aspects of beekeeping to the public. We accomplish this through direct consultations, our website (http://www.ent.uga.edu/bees), the Young Harris Beekeeping Institute, exhibits, publications, classes, workshops and lectures to local, state, national and international audiences. It is also our goal to educate the general public on the importance of honey bees, other pollinators and beneficials, along with how to protect and encourage their presence. By “the general public,” I’m referring to non-beekeepers, since most beekeepers already have an understanding of the importance of honey bees. For instance, the average American doesn’t usually realize that honey bees provide 1/3 of the food consumed. It is also important that the public be informed about other pollinators and beneficial species such as. bumble bees, mason bees, sweat bees, digger bees, butterflies, moths, flies, bats, hummingbirds, and flying squirrels. When we speak of beneficials, we are talking about any organism that feeds upon or parasitizes unwanted pests in the farm, orchard, garden, landscape setting or turf grass. They benefit the growing process by reducing the extent of botanical injury by pests. These “good” insects, such as praying mantis’, ladybugs, green lacewings, tiger beetles and spiders (e.g., garden, jumping and wolf spiders), are some of the most common beneficials around. They eat agriculturally destructive insects such as whiteflies, aphids, plant bugs, and potato beetles, but, since they’re not particularly discriminate eaters, they also sometimes eat each other. Notably, most parasitoid wasps are species-specific, only attacking one type of insect. For instance, the braconid wasp, Aphidius ervi, parasitizes exclusively the pea aphid. While parasitoids can act externally or internally, the ones most important to agriculture parasitize internally. These wasps, some of which are tiny, insert their ovipositor into the host-insect of choice and lay their eggs. The eggs hatch and begin to feed on internal tissues; this eventually kills the host, which is a good thing, since now the bad bug is no longer dining in your garden or yard. Homeowners are some of the worst abusers of pesticides. Panic-stricken after having seen a bug (“Oh, my!”), too many rush off to the nearest big box store and grab the bottle that promises instant, devastating and the longest-lasting results. Then they race home, haphazardly toss a 2 “feels good” amount of the concentrate into water in a pump sprayer without reference to written instructions, and proceed to douse the garden or yard indiscriminately until saturated. Unfortunately, the “menacing intruder” that initially gave rise to this environmental tragedy was quite possibly not even a true pest. It may have just been an inconsequential passerby or, even worse, a pollinator or beneficial! The problem with using broad-spectrum pesticides is they eliminate all bugs in the system, the good along with the bad. That is why it is important to first know the beneficials from the pests. I’m not suggesting that everyone becomes an entomologist, but at least have some appreciation of the environment as a whole and be open to strategies to target specific pests. This year, our lab has been focusing on this very objective: to raise the public’s awareness of the good verses the bad bugs. Once a bug is identified as a pest, the next step is to teach homeowners to incorporate nonchemical approaches first. For example, soft-bodied insects such as aphids are no match against a strong, steady blast from a water hose. When pesticides are absolutely necessary, there are a few simple “tricks” to reduce undesired side effects. Two of the best suggestions are to apply pesticides at night and to not contaminate flowers. The first of these strategies helps since most pollinators are back home or out of the area after the sun has set. The second is important, obviously, because pollinators carry out their work by visiting the flowers, whereas most pests suck from stems or chew leaves. Using pesticides that break down rapidly is another great way to reduce their impact. Also, avoid dusts, such as SevinTM Dust, since the particulate size is similar to pollen and can be collected by bees and then fed to brood (honey bee larvae - i.e., “baby bees”). Incorporating just these few measures will dramatically reduce the effects chemicals will have on the beneficials you want to keep around your yard and garden. For more pictures from the Sunbelt Expo, go to http://www.flickr.com/photos/89497361%40N02/show/. 2013 4-H Beekeeping Essay Contest Announcement from Jenna Brown Daniel State 4-H Program Assistant Details for the 2013 4-H Beekeeping Essay Contest are now available. Please visit the Georgia 4-H Beekeeping Essay website for all contest deadlines, rules, and regulations: http://www.georgia4h.org/beekeeping/ The 2013 essay topic will be: Reducing the Usage of Bee-Killing Pesticides in my Community. This year all entries must be submitted electronically. The deadline to submit entries will be Friday, February 1, 2013; all entries should be emailed to Jenna Daniel at the following address (jbrown10@uga.edu). The University of Georgia's Entomology Department will determine the top three essays in Georgia and send the first ranked winner to compete at the national level, against states across the country. The national winner will be announced by May 1, 2013. Please encourage your youth to create their entries with the appropriate regulations stated in the entry rules found either on the website or the printable PDF Form. Additionally, youth can view previous National winning essays posted at: http://honeybeepreservation.org/category/essaycontest/. Contact Jenna Brown Daniel with any questions, comments, or concerns at (706) 542-4H4H 3 Learning Impairment in Honey Bees Caused by Agricultural Spray Adjuvants Published in PLoS ONE Timothy J. Ciarlo*, Christopher A. Mullin, James L. Frazier, Daniel R. Schmehl Department of Entomology, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, Pennsylvania Spray adjuvants are often applied to crops in conjunction with agricultural pesticides in order to boost the efficacy of the active ingredient(s). The adjuvants themselves are largely assumed to be biologically inert and are therefore subject to minimal scrutiny and toxicological testing by regulatory agencies. Honey bees are exposed to a wide array of pesticides as they conduct normal foraging operations, meaning that they are likely exposed to spray adjuvants as well. It was previously unknown whether these agrochemicals have any deleterious effects on honey bee behavior. Methodology/Principal Findings An improved, automated version of the proboscis extension reflex (PER) assay with a high degree of trial-to-trial reproducibility was used to measure the olfactory learning ability of honey bees treated orally with sublethal doses of the most widely used spray adjuvants on almonds in the Central Valley of California. Three different adjuvant classes (nonionic surfactants, crop oil concentrates, and organosilicone surfactants) were investigated in this study. Learning was impaired after ingestion of 20 µg organosilicone surfactant, indicating harmful effects on honey bees caused by agrochemicals previously believed to be innocuous. Organosilicones were more active than the nonionic adjuvants, while the crop oil concentrates were inactive. Ingestion was required for the tested adjuvant to have an effect on learning, as exposure via antennal contact only induced no level of impairment. Conclusions/Significance A decrease in percent conditioned response after ingestion of organosilicone surfactants has been demonstrated here for the first time. Olfactory learning is important for foraging honey bees because it allows them to exploit the most productive floral resources in an area at any given time. Impairment of this learning ability may have serious implications for foraging efficiency at the colony level, as well as potentially many social interactions. Organosilicone spray adjuvants may therefore contribute to the ongoing global decline in honey bee health. Read the entire paper at: http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0040848 4 President Obama Not the Only One Drinking Honey Ale by Kendall Jones Principle Writer at the Washington Beer Blog The garden grows vigorously at the Washington Beer Blog World Headquarters. Veggies, fruit trees, flowers, hops, all of it grows remarkably well. This is due in large part to our next-door neighbors and the 30,000 bees they keep in their backyard. All day long, they are out there doing their work and helping our garden grow. Along with the food we harvest, fresh and delicious honey is a byproduct of the bees’ hard work - honey which can be used in beer. The circle of life. It turns out the gardeners at the White House also keep bees. The similarities between our house and that iconic abode do not end there. Much like the residents of the Washington Beer Blog World Headquarters, the current occupant of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue is a fan of craft beer. The White House recently released the recipe for the President’s homebrew, which is brewed using honey from the White House’s bees: White House Honey Brown Ale. Closer to home, Salish Lodge also keeps bees to help promote a healthy garden. Located at Snoqualmie Falls, Salish Lodge consistently ranks among the best small resorts in the world. This year, the lodge and Snoqualmie Falls Brewing teamed up to make a beer using honey from the Salish Lodge bees. We will have more information in the coming weeks for you about the Salish/Snoqualmie Falls honey beer project, including information about where you can drink it. Don’t laugh at the White House kitchen staff. They feed the first family and they serve fine food to dignitaries from around the world, but when it comes to brewing, the staff admits they are newbies. The White House Honey Brown Ale is an extract beer. Who knows? Maybe if the President wins a second term, he will pony up for an all-grain system. Exactly why they opted to use English hop varieties is a bit of a mystery. Sure, maybe it was a matter of taste, but someone needs to have a word with the White House and urge them to use Cascade, Willamette and other beautiful Northwest varieties. Sam Kass is White House Assistant Chef and the Senior Policy Adviser for Healthy Food Initiatives. In a recent blog post, Kass explains how the White House came to brew beer. “Inspired by home brewers from across the country, last year President Obama bought a home brewing kit for the kitchen,” Kass says. “After the few first drafts we landed on some great recipes that came from a local brew shop. We received some tips from a couple of home brewers who work in the White House who helped us amend it and make it our own. To be honest, we were surprised that the beer turned out so well since none of us had brewed beer before.” Below is the much-anticipated recipe! 5 6 Antibiotic Resistance Killing Off Bees by Emma Goldberg Yale Daily News In the Oct. 30 issue of the mBio journal, Yale professor of ecology and evolutionary biology, Nancy Moran published a study showing that beneficial bacteria found in the guts of honeybees have acquired genes that make bees resistant to tetracycline, an antibiotic used to prevent colonydestroying infections and other bacterial diseases. Moran’s research identified eight tetracyclineresistant genes in American honeybees that were absent in honeybee populations where such antibiotic treatment is banned, suggesting that use of tetracycline has genetically altered beneficial bacteria and made colonies more prone to infection. To test bee genes for resistance to antibiotics, researchers in Moran’s lab isolated all of the bacterial DNA in bee guts and transferred them into independent DNA molecules called plasmids. These plasmids were then put into E. coli and sequenced so that the tetracyclineresistant genes could be identified. To determine how different bee populations interact with antibiotics, researchers used a technique called polymerase chain reaction to amplify bee DNA samples collected from various locations in the United States, New Zealand, the Czech Republic and Switzerland. “We found that bees from the USA, which had a long treatment history [with tetracycline], carried the most resistant genes,” said Waldan Kwong, one of the authors of the paper and a researcher in Moran’s lab. If confirmed, Moran’s research could have wide-reaching impact on American crop growth and production. Honeybee pollination plays a critical role in the $15 billion U.S. agriculture industry. The industry has been plagued by recent bee colony collapses, due primarily to bees’ contraction of the bacterial disease foul brood. University of California, Davis apiculture professor Norman Gary stressed the magnitude of the colony collapse disorder. “Only recently has the true value of honeybees been appreciated by people in this country,” Gary told the News. “The colony collapse disorder is a complex issue and many scientists are advancing theories to explain its cause.” Kwong said he hopes the research conducted in Moran’s lab will encourage beekeepers to exercise caution when introducing new antibiotics into bee colonies. “Beekeepers and the general public should be aware that application of antibiotics not only affects pathogens but also the normal healthy microbes that coexist with the host,” he said. He added, however, that further research and consultation with the beekeeping community are needed before any new policies can be introduced and implemented. Gary said bee die-offs are likely the result of multiple factors rather than a single central cause. “In the scientific community we’re hoping that honeybees will develop a resistance to the cause of the colony collapses,” he said. Moving forward, researchers in Moran’s lab are studying the health benefits and hazards posed by gut bacteria in bees. They are studying the microbes that have become resistant to tetracycline to understand the beneficial functions they perform, such as pathogen defense, as well as the negative impact they can have on bees’ immune systems. 7 “We want to understand how bacteria function in bees,” Moran said. Her lab is currently working on an experiment that exposes bees to antibiotics and analyzes their long-term effects. Though she said the team has evidence that bacteria can help bees digest food, Moran said they hope to discover other health benefits bacteria provide bees. “It’s basic work, but nothing like it has ever been done before,” she said. Long-Term Exposure to Antibiotics Has Caused Accumulation of Resistance Determinants in the Gut Microbiota of Honeybees Baoyu Tiana, Nibal H. Fadhila, J. Elijah Powella, Waldan K. Kwonga and Nancy A. Morana. Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Bioloby, Yale University, West Haven, Connecticut, USA. mBio 3[6]:e00377-12. doi:10.1128/mBio.00377-12 Antibiotic treatment can impact non-target microbes, enriching the pool of resistance genes available to pathogens and altering community profiles of microbes beneficial to hosts. The gut microbiota of adult honeybees, a distinctive community dominated by eight bacterial species, provides an opportunity to examine evolutionary responses to long-term treatment with a single antibiotic. For decades, American beekeepers have routinely treated colonies with oxytetracycline for control of larval pathogens. Using a functional metagenomic screen of bacteria from Maryland bees, we detected a high incidence of tetracycline/oxytetracycline resistance. This resistance is attributable to known resistance loci for which nucleotide sequences and flanking mobility genes were nearly identical to those from human pathogens and from bacteria associated with farm animals. Surveys using diagnostic PCR and sequencing revealed that gut bacteria of honeybees from diverse localities in the United States harbor eight tetracycline resistance loci, including efflux pump genes (tetB, tetC, tetD, tetH, tetL, and tetY) and ribosome protection genes (tetM and tetW), often at high frequencies. Isolates of gut bacteria from Connecticut bees display high levels of tetracycline resistance. Resistance genes were ubiquitous in American samples, though rare in colonies unexposed for 25 years. In contrast, only three resistance loci, at low frequencies, occurred in samples from countries not using 8 antibiotics in beekeeping and samples from wild bumblebees. Thus, long-term antibiotic treatment has caused the bee gut microbiota to accumulate resistance genes, drawn from a widespread pool of highly mobile loci characterized from pathogens and agricultural sites. IMPORTANCE We found that 50 years of using antibiotics in beekeeping in the United States has resulted in extensive tetracycline resistance in the gut microbiota. These bacteria, which form a distinctive community present in healthy honeybees worldwide, may function in protecting bees from disease and in providing nutrition. In countries that do not use antibiotics in beekeeping, bee gut bacteria contained far fewer resistance genes. The tetracycline resistance that we observed in American samples reflects the capture of mobile resistance genes closely related to those known from human pathogens and agricultural sites. Thus, long-term treatment to control a specific pathogen resulted in the accumulation of a stockpile of resistance capabilities in the microbiota of a healthy gut. This stockpile can, in turn, provide a source of resistance genes for pathogens themselves. The use of novel antibiotics in beekeeping may disrupt bee health, adding to the threats faced by these pollinators. Apivar ® Amitraz Strips Receive South Dakota Section 18 Exemption Oct 24, 2012 This past October, South Dakota received a specific exemption under the provision of section 18 of FIFRA for the use of Apivar – Amitraz in a 3.33% formulation in plastic strip form – subject to conditions and restrictions. Other states may apply for this exemption and receive a section 18 label for this varroa control product [Georgia is in the process of doing this]. Apivar is an unregistered product (EPA File Symbol 87243-R) formulated as a sustained release plastic strip impregnated with 3.33% amitraz (0.5 g active ingredient per strip) manufactured by WYJOLAB for Veto-Pharma S.A.. All applicable directions, restrictions, and precautions on the product label as well as the section 18 use directions submitted with an updated application must be followed. Label instructions are more detailed, but to summarize: To control varroa, remove honey supers before application of Apivar, use 2 strips per brood chamber with a minimum distance of 2 frames between strips. Bees should walk on the strips. Leave strips in the boxes for 42 days, then remove. Reposition as needed so bees stay in contact, then leave for 14 more days. Strips must be removed after a maximum of 56 days. A maximum of 2 treatments, spring and fall, may be made per year if varroa mite infestation reaches treatment thresholds. Honey supers must be removed before strips are used, and cannot be replaced until 14 days after strip removal. Protective gloves are required. 9 Management Calendar: January– February in Georgia If you haven’t already, you may want to plan to order queens, packages or nucs sooner than later. Some operations have already sold out of their early nucs and queens. For example, neither the Kona Queen company in Hawaii nor the CF Koehnen & Sons company in California have any more early 2013 queens available. With nectar flows occurring earlier due to the trend of warmer winters each year, swarms are hitting the trees sooner. So, you don’t want to wait until April to order queens for splits or nucs for honey production unless you will be ordering them for late summer or the following year (2014). Bee magazines offer plenty of ads from bee operations in the US. If you are unsure whom to choose, ask another beekeeper whom they would recommend. Smaller, local operations are also an option and usually within driving distance. But, again, don’t wait or you may find yourself out of luck until 2014! Due to above average temperatures experienced so far this winter, your colonies are most likely devouring their honey stores much sooner than usual. During a warm day (above 50°F), when the sun is shining and there is little to no wind, check your colonies’ food stores; however, try not to break apart the cluster. Hopefully, you left adequate honey on your hives after harvest or have been feeding syrup, accordingly. In any case, you need to inspect your colonies to make sure they are in good shape. If you find one with little honey, feeding a 2:1 (sugar:water) syrup solution is recommended. This time of year, since temperatures can fluctuate back and forth, feed colonies with inverted plastic pails, buckets or jars. Do not rely on Boardman entrance feeders, division board feeders or even baggies since the bees are unable to travel far from the cluster when temperatures drop. Avoid feeding your colonies poor quality food like brown sugar, “mystery” feed, re-melted candy, pancake syrup, molasses, fermented honey and corn syrup with industrial food additives. These contain indigestible components that can have unknown and negative consequences on bees, including dysentery. Stick to pure, cane sugar. It may be a little more expensive on the front end, but you can pay now (quality feed) or later (replacement bees). Hive protection is another consideration. During times of colder weather, mice love the warm accommodations provided by honey bee colonies. To keep out these trespassers, it is suggested to use an entrance reducer or mouse guard. Usually, guards made of metal provide the best protection since mice cannot chew through them. These entrance reducers also provide protection from cold drafts. Once February arrives, don’t forget to re-check colonies for honey stores and queen viability. Colonies will be gearing up for the upcoming nectar flow by rapidly increasing their populations; therefore, resources may dwindle. And, if pollen supplies are low, it will be a good idea to introduce pollen supplements. In the mean time, don’t slack off! This is an important time to repair your worn woodenware, as well as order and build new equipment for next spring. Best wishes for api-prosperity in the new year! 10 How to Get Georgia Bee Letter GBL can be received electronically by emailing your request to Jennifer Berry atjbee@uga.edu Bartow Beekeepers Association www.bartowbeekclub.com Chattahoochee Valley Beekeepers Association www.chattahoocheebeekeepers.co m Cherokee Beekeepers Club www.cherokeebeeclub.com Coastal Empire Beekeepers Association Coweta Beekeepers Association www.cowetabeekeepers.org East Central Georgia Bee Club Regular Meetings 7:00 pm, third Tuesday 7:00 pm bimonthly, second Monday 7:00 pm third Thursday 6:30 pm second Monday 7:00 pm second Monday 7:00 pm fourth Monday, (bi-monthly) 7:00 pm first Monday Agriculture Services Building, Cartersville Oxbow Meadows Nature Center, Columbus Lincolnton Club House, Lincolnton Southbridge Tennis Complex, Savannah Asa Powell Sr. Expo Center, Newnan, Georgia Burke Co. Office Park Complex UGA Bee Lab, 1221 Hog Mtn Rd, Watkinsville Eastern Piedmont Beekeepers Assoc. www.easternpiedmontbeekeepers. org Forsyth Beekeepers Club 6:30 pm, fourth Thursday Sawnee Mountain Visitors www.forsythbeekeepersclub.org Center, Cumming Henry County Beekeepers 7:00 pm, second Tuesday Public Safety Bldg., Route www.henrycountybeekeepers.org 155, McDonough Heart of Georgia Beekeepers 7:00 pm, third Tuesday Houston Co. Gov’t Building, Association Perry Beekeepers Club of Gwinnett 7:00 pm, second Tuesday Hebron Church, Dacula County Metro Atlanta Beekeepers 7:00 pm, second Association Wednesday www.metroatlantabeekeepers.org Mountain Beekeepers Association 7:00 pm, first Tuesday Northeast Mountain Beekeepers Association Northwest Georgia Beekeepers Association www.northwestgeorgiabeekeeper s.com Oglethorpe County Bee Club www.ocbeeclub.org Southeast Georgia Beekeepers Association Southwest Georgia Beekeepers Association 7:00 pm, second Thursday 7:00 pm, second Monday 7:00 pm, third Monday 7:00 pm, fourth Tuesday, Aug-March 7:00 pm, third Monday 11 Atlanta Botanical Garden, Atlanta Mountain Regional Library, Young Harris Habersham County Extension office, Clarksville Walker County Agric. Center, Rock Spring Oglethorpe Farm Bureau Building Contact Ben Bruce 912-487-2001 Farm Bureau Building, Moultrie Tara Beekeepers Assn (Clayton Co. area) www.tarabeekeeping.org Troup County Association of Beekeepers 7:30 pm, third Monday Kiwanis Room, Georgia Power Bldg, Forest Park 7:00 pm, third Monday 4-H Ag. Bldg. on Hwy 27 at Vulcan Rd. Beekeeping Subscriptions American Bee Journal, Hamilton, Illinois, 62341 217-847-3324 Bee Culture, 623 W. Liberty Street, Medina Ohio, 44256 330-725-6677 The Speedy Bee, P.O. Box 998 Jesup, Georgia 31598-0998 912-427-4018 Resource People for Georgia Beekeeping For a complete listing of resource people and associations please go to http://www.ent.uga.edu/bees/associations.html 12