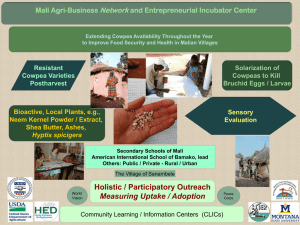

Mali Agricultural Sector Assessment

advertisement