Chapter 13 - Paleozoic Life - Vertebrates

Chapter 13

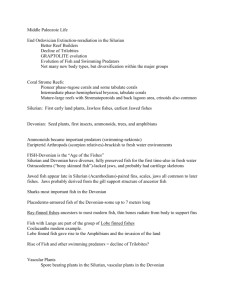

Paleozoic Life History—

Vertebrates and Plants main points…

1. Vertebrates first appeared in Cambrian,

‘Age of Fish’= Devonian

2. amphibians first appear in Devonian; very abundant during Pennsylvanian

3. Late Mississippian- evolution of amniote egg allows reptiles to colonize land…

4. pelycosaurs (fin-backed reptiles) dominate the Permian; ancestors to mammals

5. earliest land plants occur in Ordovician; oldest vascular plants appear in Mid Silurian

6. seedless vascular plants very abundant during Pennsylvanian

7. onset of arid conditions in Permian, gymnosperms dominate flora

Vertebrates and Plants

• Previously, we examined the Paleozoic history of invertebrates,

– beginning with the acquisition of hard parts

– and concluding with the massive

Permian extinctions

– that claimed about 90% of all invertebrates

– and more than 65% of all amphibians and reptiles

• In this section, we examine

– the Paleozoic evolutionary history of vertebrates and plants

Tetrapod Footprint Discovery

• The discovery in 1992 of fossilized Devonian tetrapod footprints

– more than 365 million years old

– has forced paleontologists to rethink

– how and when animals emerged onto land

• The newly discovered trackway

– has helped shed light on the early evolution of tetrapods

• the name is from the Greek tetra , meaning four and podos , meaning foot

– Based on the footprints, it is estimated

• that the creature was longer than 3 ft

• and had fairly large back legs

Tetrapod Wader

• Furthermore, instead of walking on dry land

– this animal was probably walking or wading around in a shallow, tropical stream,

• filled with aquatic vegetation and predatory fish

• This hypothesis is based on the fact that

– the trackway showed no evidence of a tail being dragged behind it

• Unfortunately, there are no bones associated with the tracks

– to help in reconstructing what this primitive tetrapod looked like

Tetrapod Footprint Discovery

• Tetrapod trackway

– at Valentia Island

Ireland

• These fossilized fooprints

– which are more than 365 million years old

– are evidence of one of the earliest four-legged animals on land

– Photo courtesy of Ken

Higgs, U. College Cork,

Ireland

Why Limbs?

• One of the intriguing questions paleontologists ask is

– why did limbs evolve in the first place

?

• It probably wasn't for walking on land

• In fact, many scientists think

– aquatic limbs made it easier to move around

– in streams, lakes, or swamps

– that were choked with water plants or other debris

• The scant fossil evidence also seems to support this hypothesis

Transition from Water to Land

• One of the striking parallels between plants and animals

– is the fact that in passing from water to land,

– both plants and animals had to solve the same basic problems

• For both groups,

– the method of reproduction was the major barrier

– to expansion into the various terrestrial environments

• With the evolution of the seed in plants and the amniote egg in animals ,

– this limitation was removed, and both groups were able to expand into all the terrestrial habitats

Characteristics of Chordates

• The structure of the lancelet

Amphioxus illustrates the three characteristics of a chordate:

– a notochord, a dorsal hollow nerve cord, and gill slits

A Very Old Chordate

• Yunnanozoon lividum is one of the oldest known chordates

– Found in 525 Myr old rocks in Yunnan province, China

– 5 cm-long animal

Fish

• The most primitive vertebrates are fish

– and some of the oldest fish remains are found in

Upper Cambrian rocks

• All known

Cambrian and Ordovician fossil fish

– have been found in shallow nearshore marine deposits,

– while the earliest nonmarine fish remains have been found in Silurian strata

• This does not prove that fish originated in the oceans,

– but it does lend strong support to the idea

Ostracoderms —

“Bony Skinned” Fish

• As a group, fish range from the Late Cambrian to the present

• The oldest and most primitive of the class Agnatha are the ostracoderms

– whose name means “ bony skin ”

• These are armored jawless fish that first evolved during the Late Cambrian

– reached their zenith during the Silurian and Devonian

– and then became extinct

Geologic Ranges of Major Fish Groups

Bottom-Dwelling Ostracoderms

• The majority of ostracoderms lived along the seafloor

•

Hemicyclaspis is a good example of a bottomdwelling ostracoderm

– Vertical scales allowed Hemicyclaspis to wiggle sideways

• propelling itself along the seafloor

– while the eyes on the top of its head allowed it to see predators approaching from above

• such as cephalopods and jawed fish

• While moving along the sea bottom,

– it probably sucked up small bits of food and sediments through its jawless mouth

Devonian Seafloor

• Recreation of a Devonian seafloor showing: an acanthodian

( Parexus ) a ray-finned fish

( Cheirolepis )

– a placoderm ( Bothriolepis ) an ostracoderm ( Hemicyclaspis )

Swimming Ostracoderm

• Another type of ostracoderm,

• represented by

Pteraspis

– was more elongated and probably active

– although it also seemingly fed on small pieces of food it could suck up

Evolution of Jaws

• The evolution of jaws

– was a major evolutionary advantage

– among primitive vertebrates

• While their jawless ancestors

– could only feed on detritus

• jawed fish

– could chew food and become active predators

– thus opening many new ecological niches

• The vertebrate jaw is an excellent example of evolutionary opportunism

– The jaw probably evolved from the first three gill arches of jawless fish

Evolution of Jaws

• The evolution of the vertebrate jaw

– is thought to have occurred

– from the modification of the first two or three anterior gill arches

• This theory is based on the comparative anatomy of living vertebrates

Acanthodians

• The fossil remains of the first jawed fish are found in

Lower Silurian rocks

– and belong to the acanthodians ,

• a group of enigmatic fish

– characterized by

• large spines,

• scales covering much of the body,

• jaws,

• teeth,

• and reduced body armor

Acanthodians most abundant during Devonian

• Although their relationship to other fish has not been well established,

– many scientists think the acanthodians

– included the probable ancestors of the present-day

• bony and cartilaginous fish groups

• The acanthodians were most abundant during the Devonian,

– declined in importance through the Carboniferous,

– and became extinct during the Permian

Other Jawed Fish

• The other jawed fish

– that evolved during the Late Silurian were the placoderms ,

• whose name means “plate-skinned”

• Placoderms were heavily armored jawed fish

– that lived in both freshwater and the ocean,

– and like the acanthodians,

– reached their peak of abundance and diversity during the Devonian

Placoderms

• The Placoderms exhibited considerable variety,

– including small bottom dwellers

– as well as large major predators such as

Dunkleosteus ,

• a late Devonian fish

• that lived in the mid-continental North American epeiric seas

– It was by far the largest fish of the time

• attaining a length of more than 12 m

• It had a heavily armored head and shoulder region

• a huge jaw lined with razor-sharp bony teeth

• and a flexible tail

• all features consistent with its status as a ferocious predator

Late Devonian Marine Scene

• A Late Devonian marine scene from the midcontinent of North America

Age of Fish

• Many fish evolved during the Devonian Period including

– the abundant acanthodians

– placoderms,

– ostracoderms,

– and other fish groups,

• such as the cartilaginous and bony fish

• It is small wonder, then, that the

Devonian is informally called the “

Age of Fish

”

– because all major fish groups were present during this time period

Cartilaginous Fish

• Cartilaginous fish

,

– class Chrondrichthyes,

– represented today by

• sharks, rays, and skates

,

– first evolved during the Middle Devonian

– and by the Late Devonian,

– primitive marine sharks

• such as Cladoselache were quite abundant

Cartilaginous Fish Not Numerous

• Cartilaginous fish have never been

– as numerous nor as diverse

– as their cousins,

• the bony fish,

– but they were, and still are,

– important members of the marine vertebrate fauna

• Along with cartilaginous fish,

– the bony fish, class Osteichthyes,

– also first evolved during the Devonian

Ray-Finned Fish

• Because bony fish are the most varied and numerous of all the fishes

– and because the amphibians evolved from them,

– their evolutionary history is particularly important

• There are two groups of bony fish

– the common ray-finned fish

– and the less familiar lobe-fined fish

• The term ray-finned refers to

– the way the fins are supported by thin bones that spread away from the body

Ray-Finned and Lobe-Finned Fish

• Arrangement of fin bones for

(a) a typical ray-finned fish

(b) a lobe-finned fish

– Muscles extend into the fin

– allowing greater flexibility

Ray-Finned Fish Rapidly

Diversified

• From a modest freshwater beginning during the

Devonian,

– ray-finned fish ,

• which include most of the familiar fish

• such as trout, bass, perch, salmon, and tuna ,

– rapidly diversified to dominate the Mesozoic and

Cenozoic Seas

Lobe-Finned Fish

• Present-day lobe-finned fish are characterized by muscular fins

• The fins do not have radiating bones

– but rather articulating bones

– with the fin attached to the body by a fleshy shaft

• Two major groups of lobe-finned fish are recognized:

– lungfish

– and crossopterygians

Lungfish Fish

• Lungfish were fairly abundant during the

Devonian,

– but today only three freshwater genera exist,

– one each in South America, Africa, and Australia

• Their present-day distribution presumably

– reflects the Mesozoic breakup of Gondwana

• Studies of present-day lung fish indicate that lungs evolved

– from saclike bodies on the ventral side of the esophagus

Amphibians Evolved from

Crossopterygians

• The crossopterygians are an important group of lobe-finned fish

– because amphibians evolved from them

• During the Devonian, two separate branches of crossopterygians evolved

– One led to the amphibians,

– while the other invaded the sea

Coelacanths

• The crossopterygians that invaded the sea,

– called the coelacanths ,

– were thought to have become extinct at the end of the Cretaceous

• In 1938, however,

– fisherman caught a coelacanth in the deep waters of

Madagascar,

– and since then several dozen more have been caught,

– both there and in Indonesia

Amphibian Ancestor

•

Eusthenopteron ,

– a good example of a rhipidistian crossopterygian,

– had an elongate body

– that enabled it to move swiftly in the water,

– as well as paired muscular fins that could be used for locomotion on land

• The structural similarity between crossopterygian fish

– and the earliest amphibians is striking

– and one of the better documented transitions

– from one major group to another

Eusthenopteron

•

Eusthenopteron ,

– a member of the rhipidistian crossopterygians

– had an elongate body

– and paired fins

– that it could use to move about on land

• The crossopterygians are thought to be amphibian ancestors

Fish/Amphibian Comparison

• Similarities between the crossopterygian lobefinned fish and the labyrinthodont amphibians

• Their skeletons were similar

Comparison of Limbs

ulna radius humerus

• Comparison of the limb bones

– of a crossopterygian (left) and an amphibian (right)

• Color identifies the bones that the two groups have in common

Tiktaalik rosea- transitional fossil

http://tiktaalik.uchicago.edu/

Comparison of Teeth

• Comparison of tooth cross sections show

– the complex and distinctive structure found in

– both crossopterygians (left) and amphibians (right)

Defenseless Organisms

• Previously, defenseless organisms either

– evolved defensive mechanisms

– or suffered great losses, possibly even extinction

• Recall that trilobites

– experienced major extinctions at the end of the

Cambrian,

– recovered slightly during the Ordovician,

– then declined greatly from the end of the

Ordovician

– to their ultimate demise at the end of the Permian

Extinction by Predation

• Perhaps their lightly calcified external covering

– made them easy prey

– for the rapidly evolving jawed fish and cephalopods

• Ostracoderms,

– although armored,

– would also have been easy prey

– for the swifter jawed fishes

• Ostracoderms became extinct by the end of the

Devonian,

– a time that coincides with the rapid evolution of jawed fish

Late Paleozoic Changes

• Placoderms also became extinct by the end of the Devonian,

– while acanthodians decreased in abundance after the Devonian

– and became extinct by the end of the Paleozoic Era

• On the other hand, cartilaginous and ray-finned bony fish

– expanded during the Late Paleozoic,

– as did the ammonoid cephalopods,

– the other major predator of the Late Paleozoic seas

Amphibians—

Vertebrates Invade the Land

• Although amphibians were the first vertebrates to live on land,

– they were not the first land-living organisms

• Land plants, which probably evolved from green algae,

– first evolved during the Ordovician

• Furthermore, insects, millipedes, spiders,

– and even snails invaded the land before amphibians

Water to Land Barriers

• The transition from water to land required that several barriers be surmounted

• The most critical for animals were

– desiccation,

– reproduction,

– the effects of gravity,

– and the extraction of oxygen

• from the atmosphere

– by lungs rather than from water by gills

Problems Partly Solved

• These problems were partly solved by the crossopterygians

– they already had a backbone and limbs

– that could be used for walking

– and lungs that could extract oxygen

A Late Devonian Landscape

• A Late Devonian Landscape in the eastern part of Greenland

•

Ichthyostega was an amphibian that grew to a length of about 1 m

• The flora was diverse,

– consisting of a variety of small and large seedless vascular plants

Amphibians —Minor Element of the Devonian

• The earliest amphibians

– appear to have had many characteristics

– that were inherited from the crossopterygians

– with little modification

• Because amphibians did not evolve until the

Late Devonian,

– they were a minor element of the Devonian terrestrial ecosystem

Rapid Adaptive Radiation

• Like other groups that moved into new and previously unoccupied niches,

– amphibians underwent rapid adaptive radiation

– and became abundant during the Carboniferous and

Early Permian

• The Late Paleozoic amphibians

– did not all resemble the familiar

• frogs, toads, newts and salamanders

– that make up the modern amphibian fauna

• Rather they displayed a broad spectrum of sizes, shapes and modes of life

Carboniferous Coal Swamp

• Reconstruction of a Carboniferous coal swamp

The serpentlike Dolichosoma

Larval Branchiosaurus

Large labyrinthodont amphibian Eryops

Labyrinthodont Decline

• Labyrinthodonts were abundant during the

Carboniferous

– when swampy conditions were widespread

,

– but soon declined in abundance

– during the Permian,

– perhaps in response to changing climactic conditions

• Only a few species survived into the Triassic

Evolution of the Reptiles — the Land is Conquered

• Amphibians were limited in colonizing the land

– because they had to return to water to lay their gelatinous eggs

• The evolution of the amniote egg freed reptiles from this constraint

• In such an egg, the developing embryo

– is surrounded by a liquid-filled sac,

• called the amnion

– and provided with both a yolk, or food sac,

– and an allantois, or waste sac

Amniote Egg

• In an amniote egg,

– the embryo is

– surrounded by a liquid sac

• the amnion cavity

– and provided with a food source

• yolk sac

– and waste sac

• allantois

• Its evolution freed reptiles

– to inhabit all parts of the land

Able to Colonize

All Parts of the Land

• In this way the emerging reptile is

– in essence a miniature adult ,

– bypassing the need for a larval stage in the water

• The evolution of the amniote egg allowed vertebrates

– to colonize all parts of the land

– because they no longer had to return

– to the water as part of their reproductive cycle

Amphibian/Reptile Differences

• Many of the differences between amphibians and reptiles are physiological

– and are not preserved in the fossil record

• Nevertheless, amphibians and reptiles

– differ sufficiently in

• skull structure, jawbones, ear location, and limb and vertebral construction

– to suggest that reptiles evolved from labyrinthodont ancestors by the Late Mississippian

• based on the discovery of a well-preserved skeleton

• of the oldest known reptile,

Westlothiana , from Late

Mississippian-age rocks in Scotland

Paleozoic Reptile Evolution

• Evolutionary relationship among the

Paleozoic reptiles

Pelycosaurs—Finback Reptiles

• The pelycosaurs ,

• or finback reptiles ,

– evolved from the protorothyrids

• during the Pennsylvanian

– and were the dominant reptile group

• by the Early Permian

• They evolved into a diverse assemblage

– of herbivores,

• exemplified by Edaphosaurus ,

– and carnivores

• such as Dimetrodon

Pelycosaurs (Finback Reptiles)

• Most pelycosaurs have a characteristic sail on their back

The herbivore Edaphosaurus

The carnivore Dimetrodon

Pelycosaurs Sails

• An interesting feature of the pelycosaurs is their sail

– It was formed by vertebral spines that,

– in life, were covered with skin

• The sail has been variously explained as

– a type of sexual display,

– a means of protection

– and a display to look more ferocious

– but...

Pelycosaurs Sail Function

• The current consensus seems to be

– that the sail served as some type of thermoregulatory device,

– raising the reptile's temperature by catching the sun's rays or cooling it by facing the wind

• Because pelycosaurs are considered to be the group

– from which therapsids (mammal-like reptiles) evolved,

– it is interesting that they may have had some sort of body-temperature control

Therapsids—

Mammal-like Reptiles

• The pelycosaurs became extinct during the

Permian

– and were succeeded by the therapsids ,

• mammal-like reptiles

– that evolved from the carnivorous pelycosaur lineage

– and rapidly diversified into

• herbivorous

• and carnivorous lineages

Therapsids

• A Late Permian scene in southern Africa showing various therapsids

– Many paleontologists think therapsids were endothermic

– and may have had a covering of fur

– as shown here

Moschops

Dicynodon

Therapsid Characteristics

• Therapsids were small- to medium-sized animals

– displaying the beginnings of many mammalian features

• fewer bones in the skull due to fusion of many of the small skull bones

• enlargement of the lower jawbone

• differentiation of the teeth for various functions such as nipping, tearing, and chewing food

• and a more vertical position of the legs for greater flexibility,

• as opposed to the sideways sprawling legs in primitive reptiles

Permian Mass Extinction

• As the Paleozoic Era came to an end,

– the therapsids constituted about 90% of the known reptile genera

– and occupied a wide range of ecological niches

• The mass extinctions

– that decimated the marine fauna

– at the close of the Paleozoic

– had an equally great effect on the terrestrial population

Losses Fewer for Plants

• By the end of the Permian,

– about 90% of all marine invertebrate species were extinct,

– compared with more than two-thirds of all amphibians and reptiles

• Plants, on the other hand,

– apparently did not experience

– as great a turnover as animals did

Plant Evolution

• When plants made the transition from water to land,

– they had to solve most of the same problems that animals did

• desiccation,

• support,

• and the effects of gravity

• Plants did so by evolving a variety of structural adaptations

– that were fundamental to the subsequent radiations

– and diversification that occurred

– during the Silurian, Devonian, and later periods

Plant Evolution

• Major events in the Evolution of Land Plants

– The Devonian Period was a time of rapid evolution for the land plants

– Major events were

– The emergence of seeds

– secondary growth

– Heterospory

– the appearance of leaves

Marine, then Fresh, then Land

• Most experts agree

– that the ancestors of land plants

– first evolved in a marine environment,

– then moved into a freshwater environment

– and finally onto land

• In this way the differences in osmotic pressures

– between salt and freshwater

– were overcome while the plant was still in the water

• The higher land plants are composed of two major groups,

– the nonvascular

– and vascular plants

Vascular Versus Nonvascular

• Most land plants are vascular ,

– meaning they have a tissue system

– of specialized cells

– for the movement of water and nutrients

• The nonvascular plants,

– such as bryophytes

• liverworts, hornwarts, and mosses

– and fungi,

• do not have these specialized cells

– and are typically small

– and usually live in low moist areas

Earliest Land Plants

• The earliest land plants

• from the

Middle to Late Ordovician

– were probably small and bryophyte-like in their overall organization

• but not necessarily related to bryophytes

• The evolution of vascular tissue in plants was an important step

– as it allowed for the transport of food and water

• Probable vascular plant megafossils

– and characteristic spores indicate

• to many paleontologists

– that the evolution of vascular plants

– occurred well before the Middle Silurian

Ancestor of Terrestrial

Vascular Plants

• The ancestor of terrestrial vascular plants

– was probably some type of green algae

• While no fossil record of the transition

– from green algae to terrestrial vascular plants exits,

– comparison of their physiology reveals a strong link

• Primitive seedless vascular plants

• such as ferns

– resemble green algae in their pigmentation,

– important metabolic enzymes,

– and type of reproductive cycle

Transitions from

Salt to Freshwater to Land

• Furthermore, the green algae are one of the few plant groups

– to have made the transition from salt water to freshwater

• The evolution of terrestrial vascular plants from an aquatic plant,

• probably of green algal ancestry

– was accompanied by various modifications

– that allowed them to occupy

– this new an harsh environment

Vascular Tissue Also Gives

Strength

• Besides the primary function

– of transporting water and nutrients throughout a plant,

– vascular tissue also provides

– some support for the plant body

• Additional strength that acts to counteract gravity is derived

– from the organic compounds lignin and cellulose ,

– which are found throughout a plant's walls

Problems of Desiccation and

Oxidation

• The problem of desiccation

– was circumvented by the evolution of cutin ,

• an organic compound

• found in the outer-wall layers of plants

• Cutin also provides additional resistance

– to oxidation,

– the effects of ultraviolet light,

– and the entry of parasites

Roots

• Roots evolved in response to

– the need to collect water and nutrients from the soil

– and to help anchor the plant in the ground

• The evolution of leaves

– from tiny outgrowths on the stem

– or from branch systems

• provided plants with

– an efficient light-gathering system for photosynthesis

Silurian and Devonian Floras

• The earliest known vascular land plants

– are small Y-shaped stems

– assigned to the genus

Cooksonia

– from the Middle Silurian of Wales and Ireland

• Upper Silurian and Lower Devonian species are known from

• Scotland, New York State and the Czech Republic,

• These earliest plants were

– small, simple, leafless stalks

– with a spore-producing structure at the tip

(sporangia)

Earliest Land Plant

• The earliest known fertile land plant was Cooksonia

– seen in this fossil from the Upper

Silurian of South

Wales

•

Cooksonia consisted of

– upright, branched stems

– terminating in sporangia

•

It also had a resistant cuticle

• and produced spores typical of vascular plants

•

These plants probably lived in moist environments such as mud flats

•

This specimen is 1.49 cm long

Early Devonian Plants

• Reconstruction of an Early Devonian landscape

– showing some of the earliest land plants

Protolepidodendron

\

Dawsonites /

- Bucheria

Early and Late Devonian Plants

• Whereas the Early

Devonian landscape

– was dominated by relatively small,

– low-growing,

– bog-dwelling types of plants,

• the

Late Devonian

– witnessed forests of large tree-size plants up to 10 m tall

Evolution of Seeds

• In addition to the diverse seedless vascular plant flora of the Late Devonian,

– another significant floral event took place

• The evolution of the seed at this time

– liberated land plants

– from their dependence on moist conditions

– and allowed them

– to spread over all parts of the land

Gymnosperms

• In the case of the gymnosperms ,

• or flowerless seed plants,

– these are male and female cones

• The male cone produces pollen,

– which contains the sperm

– and has a waxy coating to prevent desiccation,

– while the egg,

• or embryonic seed,

– is contained in the female cone

• After fertilization,

– the seed then develops into a mature, cone-bearing plant

Heterospory, an Intermediate Step

• Before seed plants evolved,

– an intermediate evolutionary step was necessary

• This was the development of heterospory ,

– whereby a species produces two types of spores

– a large one (megaspore)

• that gives rise to the female gamete-bearing plant

– and a small one (microspore)

• that produces the male gamete-bearing plant

• The earliest evidence of heterospory

– is found in the

Early Devonian plant

–

Chaleuria cirrosa ,

• which produced spores of two distinct sizes

An Early Devonian Plant

•

Chaleuria cirrosa

– from New Brunswick, Canada

– was heterosporous, producing two spore sizes

An Early Devonian Plant

• This heterosporous plant is reconstructed here

Chaleuria cirrosa

Spores of Chaleuria cirrosa

• The two spore types of

Chaleuria cirrosa

– shown at about the same relative scale

Evolution of Conifer Seed Plants

• The appearance of heterospory

– was followed several million years later

– by the emergence of pro-gymnosperms

• Middle and Late Devonian plants

• with fernlike reproductive habit

• and a gymnosperm anatomy

– which gave rise in the Late Devonian

– to such other gymnosperm groups as

• the seed ferns

• and conifer-type seed plants

Plants in Swamps

Versus Drier Areas

• While the seedless vascular plants

– dominated the flora of the Carboniferous coalforming swamps,

• the gymnosperms

– made up an important element

– of the Late Paleozoic flora,

• particularly in the non-swampy areas

Late Carboniferous and

Permian Floras

• The rocks of the Pennsylvanian Period

• Late Carboniferous

– are the major source of the world's coal

• Coal results from

– the alteration of plant remains

– accumulating in low swampy areas

• The geologic and geographic conditions of the

Pennsylvanian

– were ideal for the growth of seedless vascular plants,

– and consequently these coal swamps had a very diverse flora

Pennsylvanian Coal Swamp

• Reconstruction of a Pennsylvanian coal swamp

– with its characteristic vegetation

Amphibian Eogyrinus

Sphenopsids

• The sphenopsids,

• the other important coal-forming plant group,

– are characterized by being jointed and having horizontal underground stem-bearing roots

– many of these plants, such as

Calamites , average 5 to 6 m tall

• Living sphenopsids include the horsetail

• Equisetum

– and scouring rushes

• Small seedless vascular plants and seed ferns

– formed a thick undergrowth or ground cover beneath these treelike plants

• Living sphenopsids include the horsetail

Equisetum

Horsetail

Plants on Higher and Drier Ground

• Not all plants were restricted to the coalforming swamps

• Among those plants occupying higher and drier ground were some of the cordaites ,

– a group of tall gymnosperm trees

– that grew up to 50 m

– and probably formed vast forests

A Cordaite Forest

• A cordaite forest from the Late

Carboniferous

• Cordaites were a group of gymnosperm trees that grew up to

50 m tall

Glossopteris

• Another important non-swamp dweller was

Glossopteris , the famous plant so abundant in

Gondwana,

– whose distribution is cited as critical evidence that the continents have moved through time

Climatic and Geologic Changes

• The floras that were abundant

– during the Pennsylvanian

– persisted into the Permian,

– but due to climatic and

– geologic changes resulting from tectonic events,

– they declined in abundance and importance

• By the end of the Permian ,

– the cordaites became extinct,

– while the lycopsids and sphenopsids

– were reduced to mostly small, creeping forms

Gymnosperms Diversified

• Those gymnosperms

– with lifestyles more suited to the warmer and drier

Permian climates

– diversified and came to dominate the Permian,

Triassic, and Jurassic landscapes

Summary

• Chordates are characterized by

– a notochord,

– dorsal hollow nerve cord,

– and gill slits

• The earliest chordates were soft-bodied organisms

– that were rarely fossilized

• Vertebrates are a subphylum of the chordates

Summary

• Fish are the earliest known vertebrates

– with their first fossil occurrence in Upper

Cambrian rocks

• They have had a long and varied history

– including jawless and jawed armored forms

• ostracoderms and placoderms

– cartilaginous forms, and bony forms

• Crossopterygians

– a group of lobe-finned fish

– gave rise to the amphibians

Summary

• The link between

– crossopterygians and the earliest amphibians

– is convincing and includes a close similarity of bone and tooth structures

• The transition from fish to amphibians occurred during the Devonian

• During the Carboniferous,

– the labyrinthodont amphibians

– were dominant terrestrial vertebrate animals

Summary

• The earliest fossil record of reptiles is from the Late Mississippian

• The evolution of an amniote egg

– was the critical factor in the reptiles' ability

– to colonize all parts of the land

• Pelycosaurs were the dominate reptile group

– during the Early Permian,

• whereas therapsids dominated the landscape

– for the rest of the Permian Period

Summary

• Plants had to overcome the same basic problems as animals, namely

• desiccation,

• reproduction,

• and gravity

– in making the transition from water to land

• The earliest fossil record of land plants

– is from Middle to Upper Ordovician rocks

• These plants were probably small and bryophyte-like in their overall organization

Summary

• The evolution of vascular tissue

– was an important event in plant evolution

– as it allowed food and water to be transported

– throughout the plant

– and provided the plant with additional support

• The ancestor of terrestrial vascular plants

– was probably some type of green algae

– based on such similarities

• as pigmentation,

• metabolic enzymes,

• and the same type of reproductive cycle

Summary

• The earliest seedless vascular plants

– were small, leafless stalks with spore-producing structures on their tips

• From this simple beginning,

– plants evolved many of the major structural features characteristic of today's plants

• By the end of the Devonian Period,

– forests with tree sized plants up to 10 m had evolved

Summary

• The Late Devonian also witnessed

– the evolution of the flowerless seed plants

– whose reproductive style freed them

– from having to stay near water

• The Carboniferous Period was a time

– of vast coal swamps,

– where conditions were ideal for the seedless vascular plants

• With the onset of more arid conditions during the Permian,

– the gymnosperms became the dominant element of the world's flora

Phylum Chordata

• The ancestors and early members of the phylum

Chordata

– were soft-bodied organisms that left few fossils

– so little is known of the early evolutionary history of the chordates or vertebrates

• Surprisingly, a close relationship exists between echinoderms and chordates

– They may even have shared a common ancestor,

– because the development of the embryo is the same in both groups

– and differs completely from other invertebrates

Spiral Versus Radial Cleavage

• Echinoderms and chordates

– have similar

– embryonic development

• In the arrangement of cells resulting from spiral cleavage, (a) at the left,

– cells in successive rows are nested between each other

• In the arrangement of cells resulting from radial cleavage, (b) at the right,

– cells in successive rows are directly above each other

– This arrangement exists in both chordates and echinoderms

Echinoderms and Chordates

• Both echinoderms and chordates have similar

– biochemistry of muscle activity

– blood proteins,

– and larval stages

• The evolutionary pathway to vertebrates

– thus appears to have taken place much earlier and more rapidly

– than many scientists have long thought

Lungfish Respiration

• These saclike bodies enlarged

– and improved their capacity for oxygen extraction,

– eventually evolving into lungs

• When the lakes or streams in which lungfish live

– become stagnant and dry up,

– they breathe at the surface

– or burrow into the sediment to prevent dehydration

• When the water is well oxygenated,

– however, lungfish rely upon gill respiration

Labyrinthodonts

• One group of amphibians was the labyrinthodonts ,

– so named for the labyrinthine wrinkling and folding of the chewing surface of their teeth

• Most labyrinthodonts were large animals, as much as 2 m in length

• These Typically sluggish creatures

– lived in swamps and streams,

– eating fish, vegetation, insects, and other small amphibians

Labyrinthodont Teeth

• Labyrinthodonts are named for the labyrinthine wrinkling and folding of the chewing surface of their teeth

Carboniferous Coal Swamp

• Reconstruction of a Carboniferous coal swamp

Larval Branchiosaurus

Carboniferous Coal Swamp

• Reconstruction of a Carboniferous coal swamp

The serpentlike Dolichosoma

Permian Diversification

• The earliest reptiles are loosely grouped together as protorothyrids ,

– whose members include the earliest reptiles

• During the Permian Period, reptiles diversified

– and began displacing many amphibians

• The success of the reptiles is due partly

– to their advanced method of reproduction

– and their more advanced jaws and teeth,

• as well as their ability to move rapidly on land

Endothermic Therapsids

• Many paleontologists think therapsids were endothermic,

– or warm-blooded,

– enabling them to maintain a constant internal body temperature

• This characteristic would have allowed them

– to expand into a variety of habitats,

– and indeed the Permian rocks

• in which their fossil remains are found

– have a wide latitudinal distribution

Features Resembling

Present Land Plants

• Sheets of cuticlelike cells

• that is, the cells

• that cover the surface

• of present-day land plants

– and tetrahedral clusters

• that closely resemble the spore tetrahedrals of primitive land plants

– have been reported from Middle to Upper

Ordovician rocks

– from western Libya and elsewhere

Parallel between Seedless

Vascular Plants and Amphibians

• An interesting parallel can be seen between seedless vascular plants and amphibians

• When they made the transition from water to land,

– they had to overcome the problems such a transition involved

• Both groups,

– while successful,

– nevertheless required a source of water in order to reproduce

Plants and Amphibians

• In the case of amphibians,

– their gelatinous egg had to remain moist

• while the seedless vascular plants

– required water for the sperm to travel through

– to reach the egg

Seedless Vascular Plants Evolved

• From this simple beginning,

– the seedless vascular plants

– evolved many of the major structural features

– characteristic of modern plants such as

• leaves,

• roots,

• and secondary growth

• These features did not all evolve simultaneously

– but rather at different times,

• a pattern known as mosaic evolution

Adaptive Radiation

• This diversification and adaptive radiation

– took place during the Late Silurian and Early

Devonian

– and resulted in a tremendous increase in diversity

• During the Devonian,

– the number of plant genera remained about the same,

– yet the composition of the flora changed

Seedless Vascular Plant

• The gametophyte plants produce sperm and eggs

• The fertilized eggs grow into

• the spore-producing mature plant

• and the sporophytegametophyte life cycle begins again

Reproduction by Seed

• In the seed method of reproduction,

– the spores are not released to the environment

• as they are in the seedless vascular plants

– but are retained

– on the spore-bearing plant,

– where they grow

– into the male and female forms

• of the gamete-bearing generation

Gymnosperm Plants

• Pollen grains are transported to the female cones by the wind

• Fertilization occurs when the sperm moves through a moist tube growing from the pollen grain

• and unites with the embryonic seed

Gymnosperm Plants

• producing a fertile seed

• which then grows into a cone-bearing mature plant

Gymnosperms Free to Migrate

• In this way the need for a moist environment

– for the gametophyte generation is solved

• The significance of this development

• is that seed plants,

• like reptiles,

– were no longer restricted

– to wet areas

– but were free to migrate

– into previously unoccupied dry environments

Lycopsids

• The lycopsids were present during the

Devonian,

– chiefly as small plants,

• but by the Pennsylvanian,

– they were the dominant element of the coal swamps,

– achieving heights up to 30 m in such genera as

Lepidodendron and Sigillaria

• The Pennsylvanian lycopsid trees are interesting

– because they lacked branches except at their top

Lycopsids

• The leaves were elongate and similar to the individual palm leaf of today

• As the trees grew,

– the leaves were replaced from the top,

– leaving prominent and characteristic rows or spirals of scars on the trunk

• Today, the lycopsids are represented by small temperate-forest ground pines

Unable to Walk on Land

• Fossils of

Acanthostega ,

• a tetrapod found in 360 million year old rocks from

Greenland,

– reveals an animal with limbs,

– but one clearly unable to walk on land

• Paleontologist Jenny Clack,

• who recovered hundreds of specimens of Acanthostega ,

– points out that Acanthostega's limbs were not strong enough to support its weight on land,

– and its ribcage was too small for the necessary muscles needed to hold its body off the ground

Acanthostega Had

Gills and Lungs

• In addition,

Acanthostega had gills and lungs,

– meaning it could survive on land, but was more suited for the water

• Clack believes that

Acanthostega

– used its limbs to maneuver around

– in swampy, plant-filled waters,

– where swimming would be difficult

– and limbs would be an advantage

Unanswered Questions

• Fragmentary fossils

– from other tetrapods living at about the same time as Acanthostega

– suggest that some of these early tetrapods

– may have spent more time on dry land than in the water

• At this time, there are many more unanswered questions

– about the evolution of the earliest tetrapods

– than there are answers

• However, this is what makes the study of prehistoric life so interesting and exciting

Rhipidistians —

Ancestors of Amphibians

• The group of crossopterygians

– that is ancestral to amphibians

– are rhipidistians

• These fish, attaining lengths of over 2 m,

– were the dominant freshwater predators

– during the Late Paleozoic

Paleozoic Evolutionary Events

• Before discussing this transition

– and the evolution of amphibians,

– we should place the evolutionary history of

Paleozoic fish

– in the larger context of Paleozoic evolutionary events

• Certainly, the evolution and diversification of jawed fish

– as well as eurypterids and ammonoids

– had a profound effect on the marine ecosystem

Earliest Reptiles

• Some of the oldest known reptiles are from

– the Lower Pennsylvanian Joggins Formation in

Nova Scotia, Canada

– Here, remains of

Hylonomus are found

• in the sediments filling in tree trunks

• These earliest reptiles were small and agile

– and fed largely on grubs and insects

Hypothesis for Chordate Origin

• Based on fossil evidence and recent advances in molecular biology,

– vertebrates may have evolved shortly after an ancestral chordate acquired a second set of genes

• the ancestor probably resembled

Yunnanozoon

• According to this hypothesis,

– a random mutation produced a duplicate set of genes

– allowing the ancestral vertebrate animal to evolve entirely new body structures

– that proved to be evolutionarily advantageous

• Not all scientists accept this hypothesis and the evolution of vertebrates is still hotly debated

Evolutionary Opportunism

• Because the gills are soft

– they are supported by gill arches composed of bone or cartilage

• The evolution of the jaw may thus have been related to respiration rather than feeding

– By evolving joints in the forward gill arches,

– jawless fish could open their mouths wider

– Every time a fish opened and closed its mouth

– it would pump more water past the gills,

– thereby increasing the oxygen intake

• Hinged forward gill arches enabled fish to also increase their food consumption

– the evolution of the jaw for feeding followed rapidly

Land-Dwelling Arthropods

Evolved by the Devonian

• Fossil evidence indicates

– that such land-dwelling arthropods as scorpions and flightless insects

– had evolved by at least the Devonian

Oldest Amphibians

• The oldest amphibian fossils are found

– in the Upper Devonian Old Red Sandstone of eastern Greenland

• These amphibians,

• which belong to genera like

Ichthyostega ,

– had streamlined bodies, long tails, and fins

• In addition, they had

– four legs, a strong backbone, a rib cage, and pelvic and pectoral girdles,

– all of which were structural adaptations for walking on land

Earliest Land Plant

• The earliest plants

– are known as seedless vascular plants

– because they do not produce seeds

• They also did not have a true root system

• A rhizome,

• the underground part of the stem,

– transferred water from the soil to the plant

– and anchored the plant to the ground

• The sedimentary rocks in which these plant fossils are found

– indicate that they lived in low, wet, marshy, freshwater environments

Seedless Vascular Plants

Require Moisture

• Seedless vascular plants require moisture

– for successful fertilization

– because the sperm must travel to the egg

– on the surface of the gamete-bearing plant

• gametophyte

– to produce a successful spore-generating plant

• sporophyte

• Without moisture, the sperm would dry out before reaching the egg

Seedless Vascular Plant

• Generalized life history of a seedless vascular plant

• The mature sporophyte plant produces spores

– which upon germination grow into small gametophyte plants

Gymnosperm Plants

• Generalized life history of a gymnosperm plant

• The mature plant bears both

– male cones that produce spermbearing pollen grains

– and female cones that contain embryonic seeds

Coal-Forming Pennsylvanian Flora

• It is evident from the fossil record

– that whereas the Early Carboniferous flora

– was similar to its Late Devonian counterpart,

– a great deal of evolutionary experimentation was taking place

– that would lead to the highly successful Late

Paleozoic flora

• of the coal swamps and adjacent habitats

• Among the seedless vascular plants,

– the lycopsids and sphenopsids

– were the most important coal-forming groups

– of the Pennsylvanian Period

Vertebrate Evolution

• A chordate (Phylum Chordata) is an animal that has,

• at least during part of its life cycle,

– a notochord,

– a dorsal hollow nerve cord,

– and gill slits

• Vertebrates

, which are animals with backbones, are simply a subphylum of chordates

Fragment of Primitive Fish

• A fragment of a plate from

Anatolepis cf. A.

Heintzi from the Upper Cambrian marine

Deadwood Formation of Wyoming

•

Anatolepis is one of the oldest known fish

– a primitive member of the class Agnatha (jawless fish)

One of the Oldest Known Reptiles

• Reconstruction and skeleton of

Hylonomus lyelli from the Pennsylvanian Period

– Fossils of this animal have been collected from sediments that filled tree stumps

–

Hylonomus lyelli was about 30 cm long