A PARADIGM SHIFT IN GLOBAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LEGITIMACY

advertisement

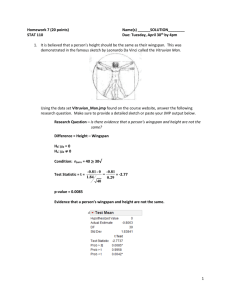

THE INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR INNOVATION: A PARADIGM SHIFT IN GLOBAL INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LEGITIMACY Question 1. What is this campaign trying to address? Access to technologies, whether they are environmentally sound technologies (ESTs) for combating climate change or essential medicines, are increasingly implicated in international human rights, such as the right to food, water, and health. As our climate continues to change, both generating and accessing these technologies will prove to be increasingly critical. Patents have evolved to become the global incentive for innovators to ensure that successful inventions produce sufficient returns on investment. However, criticism of the global patent regime has been steadily mounting on issues of global concern, particularly with respect to the inability of developing countries to access patented essential technologies. International declarations, exceptions to patent laws, and North-South joint ventures, have failed to dispel concerns over accessibility to patented products and need-based research incentives for public welfare. International trade law has tried to account for the human rights implications by allowing for "compulsory licensing" of patented technologies under a specific set of circumstances. Compulsory licensing is when a government allows a third-party to produce a patented product or use a patented process, without the consent of the patent owner. However, this solution has not been viewed either as satisfactory by developing countries in need of technologies, or sustainable by industrial innovators. Industrial innovators have been strongly discouraging the use of compulsory licensing, arguing that the use of compulsory licensing dangerously reduces the incentive for future innovation. This argument has been increasingly voiced as the 2009 Climate Change Conference approaches. Historically, developing countries have faced considerable resistance in issuing compulsory licenses, in terms of both economic and political pressure. Thus, an innovative, financial solution is needed to maintain sufficient incentive for innovation. Question 2. What is financial solution and concept? In response to the above stated problem, we propose innovation for innovation: i.e. an innovative financial mechanism to further enhance the distribution of innovation to developing countries, without sacrificing incentives for future innovation. The proposed mechanism would be achieved through the establishment of an "International Bank for Innovation," or IBI. The IBI member countries would impose a nominal fee for patent applicants and patent holders, in the form of a "guarantee premium," almost negligible relative to application and maintenance fees imposed by patent granting authorities. This "guarantee premium" would create a trust fund to finance knowledge and technology distribution to developing countries. The funds would be used for transaction costs associated with technology transfer, such as payment of licensing fees or acquisition of tangible assets needed to implement essential technologies. In the future, these funds could also be used to increase the capacity of developing countries to generate innovative solutions locally. The availability of these funds would minimize the likelihood that developing countries would be forced to resort to compulsory licensing to access technologies, thereby maintaining the incentive for inventors to continue to invest in technologies that are most needed in developing countries. In other words, the "guarantee premium" would serve as an insurance -1- premium over the risk of compulsory licensing, and could help to depolarize the growing global concern over international patent laws. Thus, the "guarantee premium" holds a dual-benefit: Developing countries would have increased access to essential technologies without fear of retaliatory measures that can result from the use of compulsory licensing, while innovators in industrialized countries would continue to research and invest in issues of global concern. The availability of these funds from the IBI could also incentivize innovators to conduct research on issues that disproportionately affect developing country populations. Unlike other financial solutions, because the guarantee premium is coupled to the global patent system, economic downturns would not significantly affect the availability of funds to the IBI. Historical trends have shown that patent applications levels do not drop in times of economic contraction, but rather remain relatively constant during such periods. The IBI awards would be limited to participating countries, based upon principles of equity and an impact assessment of the technology desired, which would be performed under recognized standards. Question 3. How will the IBI be implemented? The final goal of this project is to create the IBI, funded by the "patent guarantee" mechanism. In order to create the IBI, the project would actively guide WTO and WIPO Member States by means of legal assistance and necessary expertise in formulating the IBI and facilitating its genesis over the course of three phases, described below. Phase I (ongoing to Fall 2011): Continuing consultations with government delegates, financial and legal experts, and interested stakeholders to further develop the framework of the IBI and to build awareness for the project. An intergovernmental working group would be formed to draw a blueprint for the IBI and to host open fora for information and opinion sharing across a wide variety of sectors. Phase II (Fall 2011 to Fall 2012): The intergovernmental working group would develop the blueprint for the IBI, working closely with intergovernmental organizations, governments and interested stakeholders. The working group would establish rules and procedures for the operation of the IBI and "patent guarantee" mechanism. The progress and work of the committee would be published regularly, along with the official framework for the mechanism of the IBI. Phase III (Fall 2012 to Spring 2014): The working group would begin the implementation of the IBI at a pilot phase. Assistance and analysis would be provided for legal and technical issues in implementing the IBI and "patent guarantee" mechanism. The pilot phase would help to ensure a high-level of participation among potential participants, as the IBI is scaled up. The IBI is envisioned as within the auspices of a major international organization, such as the WTO and the WIPO. Thus, during this phase, the working group would also explore which organization might be best suited for the IBI, and if one is deemed appropriate, to facilitate the integration of the IBI into that organization. Question 4. How innovative is the IBI? The novelty of our proposal lies in the creation of a mechanism within the global innovation system to catalyze access in developing countries to the innovations generated by that very -2- system. The idea of a user-supported financial mechanism to ensure equity, stability and balance is not new. James Tobin is credited with first developing a related idea, to ensure currency stability by way of a tax on foreign-exchange transactions. However, to the best of our knowledge, the application of this concept to the international patent regime for development-related concerns is completely novel. Current mechanisms to increase access to technologies in developing countries, such as compulsory licensing, are conflict oriented. Unlike existing approaches, the IBI would help to ensure amicable discussions on how to facilitate the transfer of environmentally sustainable technologies, essential medicines, among others, to developing countries on mutually beneficial terms. In addition, patents correct a market failure, without which innovative ideas would likely either be kept secret or copied without adequate remuneration for the efforts of innovators. Compulsory licensing has the potential to re-create this market failure, encouraging trade secret protection, leading to inefficiencies from the duplication of efforts. However, most importantly, the IBI would provide tangible benefits. More specifically, patent applications have been increasing in all major patent offices at an astounding rate, nearly doubling from 1998 to 2008. About two million patent applications were filed in 2007, at an average cost of around 12,000 USD. Thus, a one percent "guarantee premium" on applications could easily provide funds of 200 million USD, with considerable stability and potential for future growth. Question 5. What is the prospective impact of the IBI? The IBI would be able to use its collective purchasing power to negotiate lower prices for essential technologies, and then transfer these technologies to those in need. For example, Kaletra, an essential HIV/AIDS medicine, costs 1,000 USD per patient per year in Brazil. Brazil negotiated this rate from a bargaining position consisting of 600,000 citizens infected with HIV/AIDS. However, an estimated 33 million people globally are infected with HIV/AIDS, 6.7 million of which are not currently receiving treatment (according to the WHO). Thus, the IBI has the potential to bargain from a position several times greater than that of Brazil on HIV/AIDS drugs. Based on conservative estimates, the IBI could provide 500,000 people per year with Kaletra and increase the ability of patients to access such medicines at more affordable rates. ESTs, e.g. solar panels, would also benefit from the IBI's purchasing power, which could help facilitate rural access to electricity for internet access, cooking and increased productivity. The "patent guarantee" could be applied to all patent regimes with ease, due to preexisting processes collecting fees. The primary difficulty in reproduction would be gathering sufficient political will to ensure wide participation. However, given the benefits to both technology consumers and industry, a well organized campaign should produce the necessary political will. The expansion of the "patent guarantee" into over 150 countries will expand the scale of the IBI's funding and impact. In addition, the number of patent applications globally is skyrocketing. Thus, even if country participation reaches a constant level, as the number of patent applications and issued patents continue to rise, the scale of the IBI's impact will continue to increase. -3-