he Impact of Trust, Power, Communication Negotiation, and Relationship Commitment

advertisement

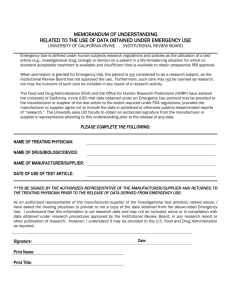

The Impact of Trust, Power, Communication Negotiation, and Relationship Commitment on a Supply Chain Integration Strategy Salahideen M. Alhaj, Linda R. Alnaqeep Computer Information Systems Department, Management Information Systems Department Faculty of Information Systems & Technology, Arab Academy, Amman-11942, Jordan. Abstract Supply Chain Integration was the main issue for many research works and received increasing attention from scholars and practitioners in recent years, despite the importance of trust, power, communication, negotiation, and commitment in relationship marketing. The understanding that commitment is crucial to the long-term success of a business relationship provides one of the core concepts in the understanding of organizational success. A lot of research work has been produced in this regard, but yet none has covered all factors of the integration process except [Alhaj and Alnaqeep 2008]. This paper proposes model and investigates the impact of the trust, power, communication, negotiation, and relationship commitment on the Supply Chain Integration Strategy (SCIS) between manufacturers and their customers, based on the critical importance of negotiation in e-commerce applications where the supply chain is dynamic and reconfiguring and a holistic perspective of customer integration by employing transaction cost theory, social exchange theory and using power–relationship commitment theory. Index Terms: Communication, Negotiation, Trust, Power, Relationship Commitment, Supply Chain Integration. Introduction Supply chain or logistics network is the system of organizations, people, technology, activities, information and resources involved in moving a product or service from supplier to customer [1]. Supply chain activities transform natural resources, raw materials and components into a finished product that is delivered to the end customer [1]. A typical supply chain is very complex [2]. However complicated [3], a supply chain could be implemented through three elements: the supply chain processes, the supply chain network structure, and the management components [2]. A supply chain involves a variety of processes: customer relationship management, customer service management, demand management, order fulfilment, manufacturing flow management, supplier relationship management, product development and commercialization, and returns management [3]. In planning and optimizing a supply chain network structure, three aspects are considered to be of major importance; the members of the supply chain, the structural dimensions of the network, and the difference types of process links across the supply chain [3]. The management components in the supply chain setting include physical-technical management components and managerialbehavioural management components [2]. Enterprises adopt supply chain practices and cope with concerned areas of supply chain implementation, they would develop diverse supply chain skills and expertise and would learn to better integrate their social and technical systems [2]. This collective learning experience is the key to improved business performance [2]. Continuous learning is very important foundation for developing supply chain competence [4], composed of nine constructs: learning encouragement, learning structure, integrative mechanisms, shared culture, commitment, trust, communication, joint decision making, and win–win approach. Improvement in service levels and reduction in costs are necessary in improving organizational performance [5]. Managers would be in a better position to meet the challenges of global supply chain processes if they understand the implementation issues and their roles on supply chain effectiveness [2]. In the other hand, social and technical systems of a supply chain are essential to improving supply chains’ overall success [6]. A good social system enables enterprises to enhance supply chain coherence, while a solid technical infrastructure helps a supply chain to gain competitive positions [2].There are some factors that influence the social side of supply chain systems [7] .The quality of supply chain practices is significantly correlated with the supplier participation strategy and influences tangible business results and customer satisfaction levels [7]. Current trends in the design and the implementation of supply chain planning and scheduling systems were reviewed; Enterprises thus need to focus on both social and technical systems of a global supply chain [2]. Supply chain management practices involve suppliers in strategic and operational decision making, encouraging information sharing and searching for new ways to integrate upstream activities [2]. It also involves developing customer contacts through the use of customer feedback to integrate the downstream activities and delivering orders directly to customers at points of use [2]. Many issues that might adversely impact supply chain performance [8] , The integration of supply chain partners may be affected by insufficient flow of information, lack of trust, lack of know-how, lack of flexibility, management problems, lack of cost visibility, partners not being EDI capable, lack of reliability, and low quality [8]. The core competencies of a firm can be described as the collective learning of the organization [4]. The emphasis is on how to coordinate diverse skill sets and integrate them into the technical system [2]. Conducting supply chain diagnostics on: integrated systems, balanced performance measurements, aligned organization structure, efficient distribution; demand driven planning, agile manufacturing, and the order to cash process proposed on [9]. In the globalize market scenario, companies need to understand and challenge the competitive markets they operate in , in addition to escalating customer expectations from point view of; delivery speed, dependability, and flexibility. Supply Chain Integration Strategy (SCIS) is one approach to achieve boundaries less market competitiveness. Supply chain integration (SCI) received increasing attention from scholars and practitioners in recent years [10], despite the importance of trust and commitment in relationship marketing [11]. Based on authors review, supply chain integration (SCI) process needs it’s own tools which is still very limited. Some research works have focused on studding the influence of interfirm relationships factors. Supply Chain Strategies and practices depend on not only the nature of the business, the competitive environment, and technological intensity of the product, but also on product and market characteristics [12].Consequently, supply chain integration (SCI) strategies should be evaluated in the light of a company’s market and product strategies [12]. In this paper, we investigate the relationship between trust, power, relationship commitment, communication and the integration of manufacturers with their customers, establishing the mechanisms of SCI based on the perspectives of power– relationship commitment theory, social exchange theory, and transaction cost theory. Specifically, our objectives are: 1.To identify the antecedents of customer integration, 2.To propose a model that represents the relationship among customer trust, power, relationship commitment, communication and customer integration in a Supply Chain, 3. To justify and develop power–relationship commitment theory in the context of an emerging economy that has a high power distance and collectivist national culture, and 4. To offer guidelines for practicing managers to enhance their performance through understanding the role of trust, power, communication in SCI and better management of customer relationships. In Section 2 authors discuss literature review. In Section 3 we proposed our SCIS Model which is the main part of the paper. In Section 4 we point out the future work. in section 5 we point out the importance of SCIS . Brief concluding remarks in Section 6 close the paper. literature review Commitment defined as the desire by a party to a business relationship to maintain and strengthen that relationship [13].The understanding that commitment is crucial to the long-term success of a business relationship provides one of the core concepts in the understanding of organizational success [14,15]. Commitment provides the basis for a cooperative spirit in marketing channel relationships and leads to an overall stronger partnership [16].The highly committed distributor is more likely to provide market intelligence to the manufacturer based on the trust that has built up in the relationship. Trust Trust and commitment are central factors that contribute to successful relationship marketing because of their ability to lead indirectly to cooperative behaviour and produce outcomes that promote efficiency, productivity and effectiveness [13]. From its root in social exchange theory [17] , commitment is one of the key concepts in relationship marketing research [18]. Commitment is an exchange party's long-term desire to maintain a valuable ongoing relationship with another [13]. In the services marketing area, relationships are built on the basis of mutual commitment [19]. Following the literature, we define customer commitment as an exchange partner's willingness to maintain an important enduring relationship [18, 20]. The literature recognizes trust as a prerequisite to building customer relationships and as a preceding state for the development of commitment [13, 20]. Trust will occur when one party has confidence in an exchange partner's reliability and integrity [13]. Because of its salience in the context of uncertainty, trust plays a critical role for service providers and B2B marketers [19]. At the same time it very clear that effective services marketing depends on the management of trust because the customer typically must buy a service before experiencing it [20]. From point view of this paper, authors define customer trust as the customer's overall perception towards the ability, benevolence and integrity of the provider [21]. Interacting with other individuals, who are inevitably independent and not fully predictable, combined with an inborn need to understand the actions of others, presents people with an overwhelming complexity. The impossibility of controlling the actions of others or even just fully understanding their motivation makes this complexity so staggering that it can actually inhibit intentions to perform many behaviors. Since people need, nonetheless, to interact on a continuous basis under such unpredictable circumstances, they apply a variety of methods for reducing this crushing complexity. Without these complexity reduction methods people could not interact with others on more than a onetime and uncommitted manner, and probably would not wish to, either [5]. Trust precedes the development of commitment. This is important to bear in mind because the two notions, although closely related, are quite distinct [11]. A.1 Quality A major prerequisite for trust is the ability to interpret the other’s true intentions .Trust leads to a high level of affective commitment. Social exchange theory explains this causal relationship through the principle of generalized reciprocity. Trust leads the involved parties to focus more on the ‘‘positive’’ motivation because of a sense of affiliation and identification with each other, and this may be a stimulus to focus less on calculative reasons for attachment to a supplier firm [11] .Trust, in a broad sense, is the confidence a person has in his or her favourable expectations of what other people will do, based, in many cases, on previous interactions [22], Based transaction cost analysis (TCA) framework, TCA scholars have argued that trust has the important effect of lowering transaction costs. However, TCA related constructs also influence the level of trust in the economic exchange. In continuous, inter-organizational transaction, trust can be either an antecedent or a consequence of any constructs, including TCA-related ones [23] the degree to which the supplier could meet the functional requirements of the purchasing managers influenced the extent to which the latter trusted their supplier [11]. Similar in the financial sector. The impact of three specific quality dimensions on trust between suppliers and buyers of hightech products investigated in [24]. That study was based on both normative and empirical assertions that trust depends on the credibility of the product and the quality of the service.They concluded that quality influences trust because hightech products are complex, technologies change rapidly and malfunctions are frequent [11]. A.2 Bonding Before trust develops, some guarantees should exist. Efficient customer bonding techniques may serve in this direction by reducing the uncertainties of the outcome of the relationship because it is a process through which the buyer and the provider build a relationship to the benefit of both parties. Writers in the field distinguish between two broad categories of bonds: structural and social [11]. Structural bonds describe ties at corporate level that, if severed, they incur considerable costs for the party responsible. They last beyond the relationships that grow between the interacting individuals [11, 25]. Specifically, in a study of the bonds that develop in the advertising industry, apart from the social bonds, identifies three more types of bonds [11]. The confidential information the agency gains about the client’s goals, internal policies or business; the inter-organizational agreements, routines and norms of conduct that develop in a relationship, making coordination easier and more efficient and the costs (monetary and not) that the client can expect to suffer if switching from its current agency [11]. Customer power Customer power is the ability of a customer to influence the decisions of a manufacturer in a supply chain [26]. Seminal work classifying power into five sources holding up to extensive empirical testing for almost 50 years. B.1 Non-Mediated Power Non- Mediated Power sources, which are more relational and positive in orientation, include expert, referent, and traditional legitimate [15, 27, 28]. Expert power Customer has knowledge, expertise or skills desired by the manufacturer, Legitimate power Manufacturer believes customer retains natural right to influence it, Referent power Manufacturer believes customer retains natural right to influence it [10, 28]. Expert, referent and legitimate power are considered non-mediated, because the manufacturer, itself, decides whether and how much it will be influenced by a customer [10]. B.2 Mediated Mediated power sources, which include reward, coercive, and legal legitimate, involve influence strategies that the source (buyer) specifically administers to the target (seller). Mediated bases represent the competitive and negative uses of power traditionally associated with organizational theory [29]. Reward and coercive power are considered mediated because their use is controlled by the customer, which can reward a manufacturer by creating positive consequences, such as placing customer orders [10]. In reward power Customer has the ability to mediate rewards to manufacturer, where in coercive power Customer has the ability to mediate punishment to manufacturer [10, 28]. National culture may play an important role in supply chain power. In a high power distance national [30] Because non-mediated power is based on the perception of the source’s power, rather than on its exercise [10]. In addition, members of high power distance national cultures are more willing to accept the use of coercive and reward power because the use of power needs less legitimization in a high power distance national culture [10]. Communication Extant research has demonstrated the necessity of two-way interorganizational communication for successful supplier relationship [31, 32]. Effective inter-organizational communication can be characterized as frequent, genuine, and involving personal contacts between buying and selling personnel [33] , at the same time communication can be classified as; Technical and Semantic. Relationship commitment Relationship commitment is the willingness of a party to invest financial, physical or relationship-based resources in a relationship [13]. In most business- to-business (B2B) exchanges, achieving a sale is not the fulfillment of an effort but rather an event in a broader endeavor to build and sustain a long-term relationship with the customer and see that sales keep coming [11]. Thus, the major issue is to examine what influences the customer’s willingness to remain with the existing supplier and furthermore to advance the relationship by investing in strengthening the ties with the supplier [11]. Product quality has traditionally been considered a major prerequisite for gaining this kind of behavioral response from the customer. However, as technology in many industries becomes a commodity, the importance of quality alone in deriving loyalty diminishes rapidly [11]. Marketing scholars have been responsive to this need. In most occasions, practitioners are advised to refocus from transactions to relationships [11]. This eventually led to the introduction and systemization of a new paradigm in marketing, that of relationship marketing [34]. Put it simply, relationship marketing seeks to cultivate a close relationship between the customer and the supplier and a sense of commitment of the former to the latter [11]. In return, the goal to obtain this sense of commitment brings the notion of trust on the top of the supplier’s agenda [11]. Within this framework, substantial empirical contribution has been derived from studies conducted within the international marketing and purchasing (IMP) group of mainly European researchers who investigated the management of relationships between suppliers and buyers [35]. Within this broader stream of research, trust and commitment are two highly interrelated notions [36]. which stimulating a relational bond between the supplier and the customer that facilitates the establishment of productive collaborations. Therefore, uncertainty in the relation is reduced, resource utilization efficiency is increased and value, for both parties, is generated [37].Despite the importance of trust and commitment though, the scholarly inquiry on the issue is hampered in three ways. One is the limited academic research to empirically document the factors that affect trust and commitment in marketing exchange relationships. Rather, the mainstream of the research effort has been directed toward the study of inter-organizational relationships such as joint ventures or less institutionalized relations with the members of the channels [37,38]. A second issue relates to the failure to distinguish trust from related factors, i.e., factors that precede the development of trust and influence it [39] On the contrary, with the notable exception of a limited number of empirical studies [13,24,37] , many empirical studies assess trust by measuring sincerity, goal congruence [40], honesty, beliefs about information sharing [41], etc. Consequently, the conditions, which vest the relationship with trust and commitment, remain veiled. Finally, a third reason is the conflicting evidence regarding the directionality of the relationship between trust and commitment. [13, 24] , for instance, suggest a causal relationship from trust to commitment,. Furthermore, when it comes to the marketing of services and specifically to B2B markets, with the exception of the study of [39], the empirical documentation is even slimmer. Yet, services are increasingly becoming a vital component of the product that the customers buy, even when it comes to such tangible products as computers or cars [42]. In view of these difficulties to underpin our understanding of trust and commitment development in B2B services marketing relationships, an investigation of two specific factors and their role in cultivating trust and commitment is attempted: The quality of the service, as it is perceived by the client, and the customer bonding techniques used by the supplier. In doing so, the causality of the relationships between the various constructs is also examined. The next of the paper is organized as follows. First, the hypotheses of the study are developed based on relevant literature. Then, the methodology that guided the research effort is discussed. Next, the analysis used to test the hypotheses is presented followed by the discussion of the findings, the implications and the suggestion for future research. The degree of trust that develops between companies has been described as a ‘‘fundamental relationship building block’’ [43] and a ‘‘critical element of economic exchange’’ [44] . The more the customer trusts the supplier, the higher the perceived value of the relationship by the customer [45] ; consequently, one can expect that the greater the chances will be that the customer remains in the relationship, as for the customer of B2B services, trust is an important element of the perceived quality of the service [46] . Trust has been conceptualized as the self-assurance that the relationship collaborators have developed reliability and integrity between them [13] and a belief that the other company will only perform actions that will result in positive outcomes [39] defined trust around the same notion: a state between two parties that are involved in a relationship according to which the party that is perceived as controlling assets (e.g., resources and know-how) that the other party values will continue sharing them in a mutually beneficial manner. [47] Suggests that trust develops successively; it is the result of a gradual deepening of the relationship through a process of mutual adaptation to the needs of the other party although not necessarily symmetrically. Research has also indicated that multiple types of trust, with both behavioral and cognitive dimensions [44] . In this study, trust is conceptualized as the confidence of the exchange actors in the goodwill of each other. It is a non calculative reliance in the moral integrity and goodwill of others on whom the exchange actors depend. Trust is then considered as a deep-rooted belief in a partner’s altruism and in the moral order of the relationship [44] . This conviction leads to integrative behavior, which eventually prolongs the duration of the relationship [48] by enhancing the dedication in the relationship [13] and serving as a means for coordination. In addition, frictions risen due to deficiencies that are inherent in all relationships are easier to solve if trust has developed [47]. Commitment is the desire for continuity manifested by the willingness to invest resources into a relationship. Many authors have described commitment as a notion including developed cooperative sentiments [49] , strong preference for existing partners [50] and propensity for relation continuity [51] . Along the same lines, [13] define commitment as the belief of an exchange partner that the ongoing relationship with another is so important as to deserve maximum efforts at maintaining it indefinitely. Similar are the opinions of [39] who conceive commitment along the same line. Interestingly enough, commitment does not appear to be equally important for both suppliers and customers. Empirical evidence exist [52] , which demonstrate that suppliers are more concerned about gaining the commitment of their customers in the relationship than vice versa. Several different motivations can underlie this intention, thus leading to two different types of commitment: affective and calculative commitment [53]. Both types are relatively stable attitudes and beliefs about the relationship but stem from different motivations for maintaining a relationship. The motive underlying affective commitment is a generalized sense of positive regard for and attachment to the other party [54]. An affectively committed company desires to continue a relationship because it likes the partner and enjoys the partnership [55]. It experiences sense of loyalty and belongingness [56].On the other hand, calculative commitment stems from an anticipation of high termination or switching costs associated with leaving from the relationship. It results from a calculation of costs and benefits which is detached from the context of the relationship itself [57] . Thus, calculative commitment is based on the perceived structural constraints that bind the firm to its partner and not a cognitive consideration of possible future opportunities provided by the latter. Consequently, relations that are based on calculative commitment continue on cost–benefit basis and after it is decided whether it is possible to leave the relation. This motivation consider as ‘‘negative’’ as compared with the ‘‘positive’’ motivation underlying affective commitment [58]. Trust leads to a high level of affective commitment. Social exchange theory explains this causal relationship through the principle of generalized reciprocity [59] . Trust leads the involved parties to focus more on the ‘‘positive’’ motivation because of a sense of affiliation and identification with each other, and this may be a stimulus to focus less on calculative reasons for attachment to a supplier firm [24]. To this direction are also the findings of a study [48] investigating the relationship between retail buyers and their vendors in the United States, which showed that the more the vendor gains in trust, the more committed the buyers become. Similar empirical findings can also be found in the studies of [, 13, 24]. Relationship commitment can be classified as normative or instrumental [27]. Normative Relationship Commitment Normative relationship commitment is a mutual, ongoing relationship over an extended period of time which is based on mutual commitment and sharing. At the heart of normative relationship commitment is trust; Mediated sources of power are inconsistent with normative relationship commitment because they are manipulative by nature [10]. Customer’s exercise of reward power manipulates the manufacturer through the provision of rewards for desired behaviors, which flies in the face of the trust that is at the heart of normative relationship commitment [10]. Negotiation Strategy At the operational planning level the task of Master Planning (MP) plays a crucial role [70]. It serves to balance supply with demand over the planning horizon and to synchronize operations across the SC [71].The implementation of a centralized MP however requires a high degree of integration among participating organizational units [70]. In a supply chain network, all manufacturing functions might be dispersed and carried out in diverse locations. In addition, a number of business entities must be collectively responsible for procurement, manufacturing and distribution activities associated with one or more families of related products. This constitutes a dynamic supply chain network design problem, where configuration of supply chain entities must coincide with the product fulfillment process. To coordinate different supply chain entities, negotiation decisions have been identified as crucial for a successful supply chain network design [60], and of critical importance in ecommerce applications where the supply chain is dynamic and reconfiguring [61]. New developments in electronic commerce promise to reduce the cost and complexity of these supply chains while promoting fast and flexible configuration [62]. From these requirements, a new class of problems has emerged and is being addressed by cooperative frameworks for manufacturing networks [63, 64, 65,66 ].We consider that a negotiation is successful, if a mutually acceptable contract is reached within reasonable time [67]. The negotiation environment considered covers multi-issue contracts and multi-party situations, while being a highly dynamic one, in the sense that its variables, attributes and objectives may change over time [67]. Second, to provide an efficient negotiation strategy, for the case where the negotiators face strict deadlines, which is in most cases private information [68]. In contrast to traditional centralized control and management systems, a supply chain network becomes a distributed paradigm, where different participants collaborate and negotiate with one another to achieve the overall functionality [69]. Why supply chain integration STRATEGY? Global competition and escalating customer expectations have forced manufacturing companies to focus more and more on delivery speed, dependability and flexibility to meet changing customer requirements [72, 73]. To enhance these capabilities, many companies have implemented supply chain integration (SCI) strategies [74]. SCI is defined as the degree to which a firm strategically collaborates with its supply chain partners and collaboratively manages intra and inter-organization processes, to achieve effective and efficient flows of products, services, information, money, and decisions, with the objective of providing maximum value to customers at low cost and high speed [74, 75]. At the tactical level, the literature suggests that there are two interrelated forms of integration that manufacturers regularly employ see figure 1. Fig .1 two interrelated forms of integration Proposed model The proposed model, see figure.2, proposes the impact of the Trust, Power [Mediated (Med) and Non-Mediated (Non-Med)], Negotiation (Neg.), and Communication(Comm.) on Relation Commitment at the first stage and the effect of on Relation Commitment [normative and instrumental] on customer integration on the second stage, based on a holistic perspective of customer integration by employing both transaction cost theory and social exchange theory and using power–relationship commitment theory, see figure 2. Figure.2: Proposed Model Future work The future work is going to be defining the hypothesis, designing the questionnaire, collecting data to examine the proposed model. We aim to target the Arabian Gulf Area. Conclusion Authors have provided a holistic perspective of customer integration by employing both transaction cost theory and social exchange theory, and investigated the impact of trust , communication , power, negotiation and relationship commitment on customer integration, using power–relationship commitment theory. This paper makes a significant contribution to the SCI and relationship management literature by proposing a model for the influence of power on relationship commitment in a supply chain context. This paper proposed that power, trust, communication negotiation, and relationship commitment are especially important for customer integration. REFERENCES [1] A. Nagurney, Supply Chain Network Economics: Dynamics of Prices, Flows, and Profits, 2006. [2] W. Chow et al , Supply chain management in the US and Taiwan: An empirical study, Omega 36 , 665 – 679 , 2008. [3] D. Lambert, M. Cooper, Issues in supply chain management. Industrial Marketing Management 29,65–83, 2000. [4] R. Spekman et al , Supply chain competency: learning as a key component. Supply Chain Management 7, 41–55, 2002. [5] R. Ballou et al , New managerial challenges from supply chain opportunities. Industrial Marketing Management 29, 7–18, 2000. [6] C . Kuei , C. Madu, Identifying critical success factors for supply chain quality management. Asia Pacific Management Review 6 ,409–23, 2001. [7] C. Lin et al , A structural equation model of supply chain quality management and organizational performance. International Journal of Production Economics 96,355–65,2005. [8] G. Knolmayer et al , Supply chain management based on SAP system. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [9] D. Allvine , T. Gore, Supply chain diagnostics. In: Gower handbook of supply chain management. Burlington, 105–19, 2003. [10] X. Zhao, B.Huo , B. Flynn , J. Yeung ,The impact of power and relationship commitment on the integration between manufacturers and customers in a supply chain, Journal of Operations Management 26 ,368–388, 2008. [11] S. Gounaris ,Trust and commitment influences on customer retention: insights from business-to-business services, Journal of Business Research 58 ,126– 140, 2005. [12] R. Narasimhan, S. Kim , Effect of supply chain integration on the relationship between diversification and performance: evidence from Japanese and Korean firms, Journal of Operations Management 20 , 303– 323, 2002. [13] R. Morgan, and S. Hunt. The Commitment Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Journal of Marketing 58, 20–38 ,1994. [14] L.Scheer, and L. Stern, The effect of Influence Type and Performance Outcomes on Attitude Toward the Influencer. Journal of Marketing Research 29, 128–142, 1994. [15] S. Andaleeb, An Experimental Investigation of Satisfaction and Commitment in Marketing Channels: The Role of Trust and Dependence. Journal of Retailing 72, 71–93,1996. [16] E.Anderson, and B. Weitz , The Use of Pledges to Build and Sustain Commitment Distribution Channels. Journal of Marketing Research 29,18– 34, 1992. [17] K. Cook, , and R. Emerson, Power, equity and commitment in exchange networks. American Sociological Review, 43(5), 721−739,1978. [18] T.Hennig-Thurau ,Understanding relationship marketing outcomes: an integration of relational benefits and relationship quality. Journal of Service Research, 4(3), 230−247, 2002. [19] L. Berry,and A. Parasuraman , Marketing services. New York: Free Press, 1991. [20] E. Garbarino, and M. Johnson,The different roles of satisfaction, trust, and commitment in customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70−87, 1999. [21] R. Mayer, et al , An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(30), 709−734, 1995. [22] D. Gefen , E-commerce: the role of familiarity and trust .the international of management since Journal Omega 28, 725-737,2000. [23] T. Suh, and I. Kwon, Matter over mind: When specific asset investment affects calculative trust in supply chain partnership. Industrial Marketing Management 35, 191 – 201, 2006. [24] K. Ruyter et al., Antecedents of Commitment and Trust in Customer– Supplier Relationships in High Technology Markets, Industrial Marketing Management 30, 271–286, 2001. [25] Han et al., Data-Driven Discovery of Quantitative Rules in Relational Databases, IEEE Transaction On Knowledge and Data Engineering, Vol. 5, No. 1, Feb 1993. [26] L. Goodman and P. Doin, the Determinants of Commitment in the Distributor–Manufacturer Relationship, Industrial Marketing Management 30, 287–300, 2001. [27] Brown et al., Power and Relationship Commitment: Their Impact on Marketing Channel Member Performance,Journal of Retailing, Volume 71(4), pp. 363-392, 1995. [28] W. Benton and M. Maloni ,The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction,2000. [29] W. Bentona, M. Malonib, The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction Journal of Operations Management 23,1–22,2005. [30] G. Hofstede, 1991. [31] A. Ansari and B. Modarress , Commercial use of expert systems in the U.S.,Journal of Systems Management, 1990. [32] G. Newman and K. Rhee,A case study of NUMMI and its suppliers. (New United Motor Manufacturing Inc, Journal of Purchasing & Materials Management, 1990. [33] I. Chen, A. Paulraj, Towards a theory of supply chain management: the constructs and measurements. Journal of Operations Management 22,119– 150, 2004. [34] E. Gummesson , Total relationship marketing. Rethinking marketing management,1999. [35] H. Ha°kansson , An interaction approach. In: International marketing and purchasing of industrial goods, p. 10– 27, 1982. [36] N. Kumar, et al , The effects of perceived interdependence on dealer attitudes,1995. [37] M. Sarkar , The strategic role of relational bonding in inter-organizational collaborations: an empirical study of the global construction industry , 85– 107,1998. [38] J. Gullen ,Japanese and local partner commitment to IJVs: psychological consequences of outcomes and investments in the IJV relationship, 91– 116,1995. [39] C. Moorman, et al ,Factors affecting trust in market research relationships, 57:81–101,1993. [40] Sullivan J, Peterson R. Factors associated with trust in Japanese– American joint ventures. Manage Int Rev 1982;22:30–40. [41] Crosby L, Evans K, Cowels D. Relationship quality in services selling: an interpersonal influence perspective. J Mark 1990;54:68–81. [42] Zeithaml VA, Bitner MJ. Services marketing. Singapore: McGraw-Hill; 1996. [43] Wilson D. An integrated model of buyer– seller relationships. J Acad Mark Sci 1994;4:335 – 45. [44] Ring PS. Fragile and resilient trust and their roles in economic exchange. Bus Soc 1996;35:148–75. [45] Walter A, Holzle K, Ritter T. Relationship functions and customer trust as value creators in relationships: a conceptual model and empirical findings for the creation of customer value. Proceedings of the 18th IMP Conference, Dijon, France; 2002. [46] Turnbull P, Moustakatos T. Marketing and investment banking: II. Relationships and competitive advantage. Int J Bank Mark 1996;14:38 – 49. [47] Ho¨gberg B. Trust and opportunism in supply chain relationships. Proceedings of the 18th IMP Conference, Dijon, France; 2002. http://www.escdijon.com/fr/imp/papers.usp. [48] Ganesan S. Determinants of long term orientation in buyer– seller relationships. J Mark 1994;58:1– 19. [49] Childers TL, Ruekert RW. Towards a model of cooperative sentiments and their antecedents in channel distribution. Working paper, School of Management, University of Minnesota; 1986. [50] Teas RK, Sibley SD. An examination of the moderating effect of channelmember firm size on perceptions of preferred channel linkages. J Acad Mark 1980;277– 93. [51] Anderson E, Weitz BA. Determinants of continuity in conventional industrial channel dyads. Mark Sci 1989;8:310– 23. [52] Leek S, Naude´ R, Turnbull PW. Managing business-to-business relationships: an emerging model. Proceedings of the 18th IMP Conference, Dijon, France; 2002. [53] Mathieu JE, Zajac DM. A review and meta-analysis of the antecedents, correlates and consequences of organizational commitment. Psychol Bull 1990;108:171–94. [54] Konovsky MA, Cropanzano R. Perceived fairness of employee drug testing as a predictor of employee attitudes and job performance. J Appl Psychol 1991;76:689–707 [55] Buchanan B. Building organizational commitment: the socialization of managers in work organization. Adm Sci Q 1974;19:533–46. [56] Jaros SJ, Jermier JM, Koebler JW, Sincich T. Effects of continuance, affective, and moral commitment on the withdrawal process: an evaluation of eight structural equation models. Acad Manage J 1993; 36:951– 95. [57] Allen NJ, Meyer JP. The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. J Occup Psychol 1991;63:1– 18. [58] Geyskens I, Steenkamp JB, Scheer LK, Kumar N. The effects of trust and interdependence on relationship commitment: a trans-Atlantic study. Int J Res Mark 1996;51:303–18. [59] McDonald GW. Structural exchange and marital interaction. J Marriage Fam 1981;30:825– 39. [60] Jianxin (Roger) Jiao et al, An agent-based framework for collaborative negotiation in the global manufacturing supply chain network, Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing 22 (2006) 239–255. [61] R. Wilhelm et al, Electronic Commerce Negotiation in a Supply Chain Via Constraint Evaluation [62] Thomas, D. J., Griffin, P. M., 1996, Coordinated supply chain management, European Journal of Operational Research, 94/1:1-15. [63] Wiendahl, H.-P., Lutz, S., 2000, Production in Networks, Annals of CIRP, 51/2:573-586. [64] Tseng, M.M. , Lei, M., Su, C.J., Merchant, M.E.,1997, A collaborative control system for mass customization manufacturing, Annals of CIRP, [65] Schuh, G., Bergholz, M., Westkamper, E, 2003, Collaborative Production on the Basis of Object Oriented Software Engineering Principles, Annals of [66] Scholz-Reiter, B., Hohns, H., Hamann, T., 2004, Adaptive Control of Supply Chains: Building blocks and tools of an agent-based simulation framework,Annals of CIRP, 53/1:353-356. [67] Malamati Louta et al , An intelligent agent negotiation strategy in the electronic marketplace environment, European Journal of Operational Research 187 (2008) 1327–1345. [68] Vulkan, N., 1999. Economic implications of agent technology and ecommerce. The Economic Journal 109 (453), 67–90. [69] Sadeh NM, Hildum DW, Kjenstad D, Tseng A. MASCOT: anagent-based architecture for dynamic supply chain creation and coordination in the internet economy. Prod Plan Control 2001; 12(3):212–23. [70] Gregor Dudek , Hartmut Stadtler, Negotiation-based collaborative planning between supply chains partners,European Journal of Operational Research 163 (2005) 668–687. [71] Rohde, J., Wagner, M., 2002. Master Planning. In: Stadtler, H., Kilger, C. (Eds.), Supply Chain Management and Advanced Planning, second ed. Berlin, pp. 143–160. [72] Boyer, K.K. Lewis, M.W., 2002. Competitive priorities: investigating the need for trade-offs in operations strategy. Journal of Operations Management 11(1), 9-20. [73] Flynn, B.B. Flynn, E.J., 2004. An exploratory study of the nature of cumulative capabilities.Journal of Operations Management 22(5), 439-458. [74] Bowersox, D.J., Closs, D.J., Stank, T.P., 1999. 21st century logistics: making supply chain integration a reality. Council of Logistics Management, Oak Brook, IL. [75] Frohlich M.T. Westbrook, R. 2001. Arcs of integration: An international study of supply chain strategies. Journal of Operations Management 19(2), 185-200.