Chapter 14 International Budgeting and Performance Evaluation

advertisement

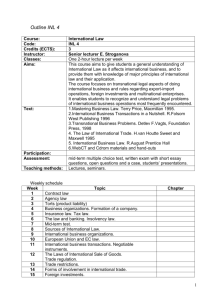

Chapter 14 International Budgeting and Performance Evaluation The Strategic Control Process Four stages of strategic control Periodic strategy reviews for each business Annual operating plans Formal monitoring of strategic results Personal rewards and central intervention Benefits from a former control process Greater clarity and realism in planning More “stretching” of performance standards More motivation for business unit managers More timely intervention by central management Clearer responsibilities International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black The Strategic Control Process Difficult to implement this process in a global environment Different operating environments include Legal systems Political differences Economic systems (inflation, market size, growth) International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Target measures for strategic purposes Return on investment Sales Cost reduction Quality targets Market share Profitability Budget to actual Targets for a unit should be linked to its objective and to the part of operations it controls International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Studies of U.S. Multinationals Robbins and Stobaugh (1973) conclusions Tangible and intangible items that entered into the original investments calculations were rarely taken into account in evaluating the foreign subsidiaries’ performance Foreign subsidiaries were judged on the same basis as domestic subsidiaries Most utilized measure of performance for subsidiaries was ROI Nearly all multinationals used some supplementary measure to evaluate performance Most widely used supplementary measure was comparison to budget International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Studies of U.K., Japanese Multinationals Appleyard, Strong, and Walton (1990) Shields, Chow, Kato, Nakagawa (1991) British companies tend to use budget/actual comparisons and ROI British firms use the same ROI measure for all subsidiaries Japanese companies tend to rely on sales Insert Exhibit 14.2 Bailes and Assada (1991) ROI tends to be relatively unimportant to Japanese firms International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Studies of APEC Multinationals Merchant, Chow, and Wu (1995) Kong, Harrison, Harrell (1994) Little evidence suggesting a link between national culture and firms’ goals in Taiwan Sample only had 4 firms Anglo-American managers prefer short term, quantitative objectives Asian firms tend to choose objectives that fit a long-term market dominance strategy International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting studies Anglo-American practice Budget process is improved by the participation of those who carry out the budget Brownell (1982) – for budget participation to work, managers must feel like insiders Mexican companies Frucot and Shearon (1991) found a similar approach in Mexican companies Insider/outsider dimensions did not matter Mexican managers of foreign owned subs showed almost no desire to participate in budgeting International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting studies APEC Multinationals Harrison (1992) found that both Australia and Singapore prefer participative style Budgetary participation universally enhances job satisfaction regardless of culture Finnish MNE Hassel and Cunningham (1996) found that higher exchange of info between headquarters and domestic subs increases performance Exchange of info had no effect on foreign subs Market and technology info exchange is a major advantage for domestic subsidiaries International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting Studies U.S./Japan Comparisons – Bailes and Assada American companies take 12 days longer to prepare annual budgets Major objective for U.S. companies is ROI; Japanese companies focus on sales Division managers participate in budget committee discussions more in the U.S. Japanese companies follow a bottom-up approach; managers’ wishes are less important than group consensus Japanese managers are more likely to use budget variances to recognize problems American managers are more likely to be evaluated by the budgets Bonus and salary of American managers are more affected by budget performance than those of Japanese managers International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting studies U.S./Japan Comparisons Ueno and Sekaran (1992) U.S. budget managers tend to create more “slack” This behavior is linked to individualism Japanese managers tend to have a long-term focus for performance International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting studies Interaction of Culture and Geographic Distance Hassel and Cunningham (2004) findings Subsidiaries with low psychic distance show stronger financial performance Psychic distance – combination of culture and geographic distance Findings suggest that budget controls work most effectively for subs that are closer to the parent in psychic distance International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Planning and Budgeting Issues Currency determination is a major issue “After-translation” basis is used if the goal is to maximize domestic purchasing power “Before-translation” basis is used if the goal is global optimization Local currency is more indicative of the overall operating environment Translating budgets into the parent currency allows a firm-wide view of the upcoming year International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Planning and Budgeting Issues Three approaches in dealing with foreign exchange in the budgeting process Allow operating managers to enter into hedge contracts with corporate treasury Adjust the actual performance of the unit for variations in the real exchange rate after the end of the period Adjust performance plans in line with variations in the real exchange rate International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Ways to Bring Foreign Exchange into the Budgeting Process International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Budgeting and Currency Practices Study of British subs of Japanese firms (Demirag 1994) “Companies that indicated that financial statements presented in sterling (local currency) provided them with better understanding of the performance of their companies’ operations and their management…None of the companies translated their profit budgets into yen for performance evaluation purposes…[and] none of the parent companies sent a copy of the translated yen statements.” None of the sub managers were aware of their performance in parent currency terms International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Capital Budgeting MNEs use sophisticated techniques to forecast cash flows, assess risks, and determine the right discount rate for NPV Hasan et al. (1997) findings Subs that are majority owned by the parent company were more likely to use NPV and IRR Subs that were large, publicly traded, and wellestablished use more complex methods (WACC) Can ROI be used to evaluate individual operations and individual managers? International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Intracorporate Transfer Pricing Prices should be based on production costs, but often are not Companies face the dilemma between complying with tax laws and maximizing profits Transfer pricing manipulation can occur Arm’s length standard is used by tax authorities to combat this problem One set of prices for both performance evaluation and arm’s length standards could be used International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Intracorporate Transfer Pricing Managers must be careful in this area DHL was fined $60 million for inappropriate transfer pricing of intangible assets (Przysuski et. al, 2003) Eden (2001) – 3 trends that will play a major role in transfer pricing in the coming years Globalization Regionalization The Internet International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Matching Price to Market Conditions International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Allocation of Overhead Firms must decide what to do with it Example How does IBM, headquartered in New York, allocate overhead to its operations in different countries? What are the tax implications of this issue? International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Cross-Border Allocation of Expenses Differing tax rates complicate the situation Using tax law to allocate overhead can eliminate the possibility for a firm to allocate overhead based on manufacturing strategy Hiromoto (1988) study of Japan shows that Japanese managers are concerned about how allocation of costs motivates employees Japanese teach us that overhead is lowered permanently only through controllable and highly integrated manufacturing processes International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Performance Evaluation Issues Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) findings Global innovators and integrated players need evaluation systems that are flexible compared to implementers or local innovators Global innovators and integrated players rely more on behavioral controls and less on output controls Global innovators need more autonomy than implementers Global innovators rely more on internal control of performance than external control International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Performance Evaluation Issues No single basis of performance evaluation is appropriate for all units of an MNE Multiple bases for performance measurement should be used for different operations Must be cost-beneficial Proper measures should eliminate uncontrollable impacts due to interdependencies between units International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Properly Relating Evaluation to Performance Performance measures can be manipulated Example – the ROI income denominator can be increased by increasing intracorporate transfer prices above the arm’s length standard Solution: compare performance to the plan given to the subsidiary Limitations include Illogical and unreasonable plans Managers’ inputs to plan are bleak so the plan can be surpassed International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Economic Value Added (EVA) EVA = After-tax profit – Total cost of capital Measure of the total value added or depleted from shareholder value in one period Used primarily for performance evaluation and compensation rather than for capital budgets Differences in accounting standards and changing currency values can influence EVA Managers should consider the risks to international investing to obtain correct costs of equity and debt International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Economic Value Added (EVA) EVA = [ROIC – WACC] * AIC ROIC = Return on invested capital = Operating profit minus cash taxes paid divided by average invested capital WACC = Weighted average cost of capital = (Net cost of debt * % debt used) + (Net cost of equity * % equity used) AIC = Average invested capital = Average stockholders equity + average debt International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black Economic Value Added (EVA) Total revenues Total costs Total operating expenses Cash taxes paid Stockholders Equity (Average) Debt (Average) After-tax cost of debt % debt used Cost of Equity % equity used $6,500 (million) 4,000 1,800 230 1,500 2,370 5.5% 40% 15% 60% Operating Profit = 6500 – 4000 – 1800 – 230 = 470 AIC = 1,500 + 2,370 = 3,870 ROIC = 470/3,870 = 12.1% WACC = (5.5% *.40) + (15% +.60) = 11.2% EVA = (12.1% - 11.2%) * 3,870 = 34.83 > cost of capital, value is added International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black The Balanced Scorecard Developed by Kaplan and Norton (1992) Takes a broader view of performance Bain & Co. results (Gumbus and Lyons 2002) 50% of Fortune 1,000 North American companies use the balanced scorecard 40% of European companies use a version of the BSC Perspectives in the scorecard include Financial Customer Internal business processes Learning and growth International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black The Balanced Scorecard IKEA uses the BSC approach, as does Philips Adequate use of the BSC Helps managers avoid using only one performance measure Forces managers to link financial measures with the non-financial factors that drive them Ensures that subs are evaluated based on a coherent set of performance bases Insert Exhibit 14.10 International Accounting & Multinational Enterprises – Chapter 14 – Radebaugh, Gray, Black