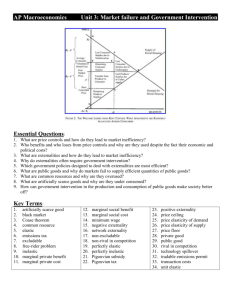

08_Market Failure and Allocation Function_Overhead Slides

advertisement

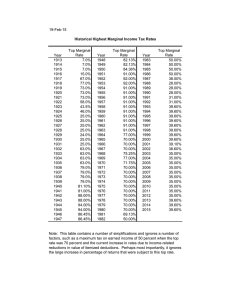

Market Failure and the Allocation Function of Govt: (“Economics” – Chapter 10) Recall, free market outcomes are often efficient… But, even in a market oriented economy (e.g., U.S.), government plays a substantial role in the economy One way to see how much the government is doing is to look at Government Spending as a Percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) Government Expenditures as a Percentage of GDP: Sweden Finland France Germany Canada Spain Ireland Japan U.S. Korea 1991 61.4 56.7 50.6 46.1 52.3 44.3 44.5 31.6 37.8 19.9 1994 68.4 63.7 54.2 47.9 49.7 46.7 44.0 35.5 37.0 20.0 1997 60.7 56.2 54.1 48.3 44.3 41.6 36.7 35.7 35.4 21.3 2000 57.0 48.3 51.6 45.1 41.1 39.1 31.5 39.0 34.2 22.6 2003 56.0 50.1 53.2 48.4 41.2 38.4 33.4 38.4 36.8 29.2 2006 52.9 48.6 52.7 45.3 39.4 38.5 34.0 36.2 36.5 28.4 Mean from 1991-2006 60.58 54.58 53.02 47.92 44.90 41.66 37.30 36.91 36.32 23.23 Government spending in U.S. as a % of GDP: Has consistently increased over time 1792 to 1901 (just Federal) 1902 to 1917 1918 to 1967 1968 to 2007 2008 to 2015 mean median min 2.744182 2.305 1.05 7.9525 7.99 6.64 24.3988 23.825 11.24 36.7395 37.12 32.03 43.40875 43.325 40.47 max 13.27 9.86 53.44 39.86 46.49 max year 1865 1915 1945 1992 2009 1 During the period from 1918 to 1967, this figure increased steadily was abnormally high from 1943 to 1946 1943 47.17 1944 50.51 1945 53.44 1946 36.27 If we re-create the table above, but do not include the years from 1943 to 1946… 1792 to 1901 (just Federal) 1902 to 1917 1918 to 1967 (not 43-46) 1968 to 2007 2008 to 2015 mean median min 2.744182 2.305 1.05 7.9525 7.99 6.64 22.44674 22.61 11.24 36.7395 37.12 32.03 43.40875 43.325 40.47 max 13.27 9.86 31.65 39.86 46.49 max year 1865 1915 1967 1992 2009 For each of the last three rows, the “minimum value” is greater than the “maximum value” from the row above Before 2008, government spending was never above 40% of GDP (except in 1943, 1944, and 1945) 2008 2009 2010 2011 40.47 46.49 45.03 44.16 2012 2013 2014 2015 43.99 42.66 42.25 42.22 If markets are so great (i.e., efficient), then why would we want government playing such a large role in the economy? 2 Government Intervention in markets and the economy is most often justified by arguing for government to serve one of the three following functions: 1. Allocation Function – government production of goods or regulation of business, aimed at improving the allocative efficiency of the economy (i.e., getting the “right mix” of products produced, each in the “ideal quantity” and at the “ideal quality”). 2. Distribution Function – government policies aimed at changing the final distribution of goods/services across consumers, usually with the intention of realizing a “fairer” apportionment of consumption/income/wealth. 3. Stabilization Function – attempts by government to minimize fluctuations in overall macroeconomic activity For the remainder of this topic, we will focus on the “Allocation Function” of Government 3 Government intervention may be able to improve upon the allocation of resources in the presence of “market failure” Market Failure – a situation in which the “free market outcome” is inefficient, in that there is a positive Deadweight-Loss at the resulting “free market level of trade.” Recall, for market outcomes to be efficient several conditions must be met. If these conditions are not met, then the market outcome will not be efficient (Positive Deadweight-Loss). In the presence of Market Failure, government intervention may be able to improve the outcome (i.e., have us realize an outcome with a smaller Deadweight-Loss). Four common phenomena leading to Market Failure: I. Market Power II. Public Goods III. Externalities IV. Lack of Information 4 I. Market Power. When there are not “many participants” on one side of a market, then some individuals can have “substantial control over price” As a result, prices may deviate from “marginal costs” (or “marginal benefits”), leading to an inefficient level of trade In a “perfectly competitive market” sellers have “no control over price” “Many other sellers,” each selling an “identical item” If a seller tries to charge more than the “prevailing market price,” nobody will buy their output There are “so many buyers,” so that the firm can always sell one more unit of output at the current market price A firm in a perfectly competitive market faces a demand curve that is a “horizontal line” at the prevailing market price $ (Prevailing market price) = $10 Demand facing firm in perfectly competitive market 0 quantity 0 5 Market Power – A firm has market power if they have some “control over the price of their output,” in that they i. can increase price without losing all customers ii. must decrease price in order to increase sales Monopoly – market structure in which there is one single seller of a unique good with no close substitutes. The “polar opposite” of “perfect competition.” The demand curve facing a monopolist is the market demand curve. They can choose any price/quantity combination along the market demand curve. Profit Maximization for a Monopolist: “downward sloping demand” => “marginal revenue is below price” $ Marginal Costs of Production Demand 0 quantity 0 Marginal Revenue of Firm 6 $ Consumers’ Surplus Profit Maximizing Price Monopoly Surplus Deadweight-Loss Marginal Costs of Production Demand 0 0 q M Profit Maximizing Quantity Sold Efficient Quantity q E of Trade quantity Marginal Revenue of Firm When maximizing profit, the monopolist only sells those units for which “Marginal Revenue” is greater than “Marginal Costs” “Profit Maximization” => trade up to q M . To maximize “Total Social Surplus” we would need to trade all units for which “Buyer’s Reservation Price” (illustrated by “Height of Demand Curve”) is greater than “Seller’s Reservation Price” (illustrated by “Height of Marginal Cost Curve”) “Efficiency” => trade up to q E . “Inefficiency due to underproduction” ( qM qE ) illustrated by the gray shaded area above (positive DWL) “Monopoly Surplus” illustrated by orange shaded area; Consumers’ Surplus illustrated by green shaded area Positive DWL is “the reason why monopoly is bad”… 7 II. Public Goods. Goods can differ with respect to their “excludability” and “rivalness in consumption”: Non-Rival Good – a good for which consumption by one person does not diminish the quantity or quality of consumption by others Rival Good – a good for which consumption by one person does diminish the quantity or quality of consumption by others Non-Excludable Good – a good for which it is difficult (or very costly) to prevent consumption by those who do not pay Excludable Good – a good for which it is easy to prevent consumption by those who do not pay Private Good – a good that is excludable and rival in consumption. Example: a “Big Mac” from McDonald’s. Rival: if I get the benefits of eating the Big Mac, you cannot also get the benefits of eating the Big Mac. Excludable: McDonald’s could easily sell a Big Mac to me, but not to you (i.e., they could easily exclude someone from consuming the good if they refuse to pay for it) Market provision of Private Goods is generally efficient. 8 Public Good – a good that is non-excludable and non-rival in consumption Classic example: National Defense. Non-rival: the amount of national defense that we are enjoying in this room right now would not decrease if one more student had come to class today. Non-excludable: there is no way to provide me with a certain level of national defense as I am giving my lecture, but at the same time prevent you from enjoying the benefits of the good. Also, define… Club Good – a good that is excludable and non-rival in consumption e.g., satellite radio or television broadcast Common Good – a good that is non-excludable and rival in consumption e.g., stock of fish in the ocean Degree of Excludability Club Good (Satellite TV) Public Good (National Defense) Private Good (Big Mac) 1 Degree of Rivalness 0 0 1 Common Good (fish in the ocean) 9 Provision of a Pure Public Good: Example: F-22 Raptor – cost of $150 million per jet Consider the choice of “building the next F-22” Suppose that each of the 150 million U.S. households has an “average value” of $4 for “one more F-22” Would the free market provide another unit? Is it efficient to provide another unit? Implications of a good being a “public good”… non-rival: so long as the good is provided (by someone), each person gets “all the benefits” of the good => the “Social Benefits” of providing a unit are equal to “the sum of the private benefits” of providing the unit In this example, the “Social Benefits” are $600 million while the Social Costs are $150 million => efficient to produce one more unit 10 non-excludable: even if someone “doesn’t contribute any money toward paying for the good,” they still get to “enjoy the benefits of the good” => there is in essence no effective way to charge for the good Suppose we decided whether or not to produce “one more F-22 Raptor” by (i) asking everyone to state their “marginal benefit for one more F-22” (ii) producing one more unit if the stated marginal benefits add up to more than $150 million (i.e., if the stated Social Benefits are greater than the Social Costs) (iii) asking each person to pay a fraction of costs equal to “their stated fraction of Social Benefits” Fixing the answers of others, I will claim “no benefit from another F-22” (even though my benefit is $4) This “false answer” will almost certainly not change whether the unit is or is not provided (i.e., it almost certainly will not change whether the “sum of stated values is above or below $137.5 million”), and I will have to contribute ($0) toward paying for the good! When we all behave like this, zero units would be provided (most certainly not optimal) Recognize that this mechanism for providing the good is very similar to how the market would go about providing the good => market provision of Public Goods is generally inefficient, because of the “Free Rider Problem” 11 Free Rider Problem – if a public good were supplied in a free market, the amount traded would be less than the efficient quantity, since many people would attempt to enjoy the benefits of units purchased by others, while not purchasing any units themselves i.e., many “self-interested” people would rationally try to “free ride” on units purchased by others we might still expect a “positive amount to be provided” (e.g., maybe Bill Gates and Warren Buffett might buy “a few F-22’s”), but the amount purchased would be “less than the efficient amount” How to “correct” for this inefficiency? How did we, in the United States, “decide” to put 187 F-22 Raptors into service between 2005 and 2011? we did not rely on markets, but rather we relied on government… a government agency supplied these goods through our political process we elected officials who appointed bureaucrats and made budgetary decisions which ultimately resulted in a “choice” of this level through the same process, taxes were imposed to cover the costs of production note: we do not know that “187 units” is the efficient quantity, but we do know (with certainty) that the quantity which a free market would provide is less than the efficient quantity (whatever the efficient quantity happens to be) 12 III. Externalities. Some activities result in benefits or costs for individuals who are not “directly involved in the activity” (i.e., an “external effect” or “externality”) External Cost or Negative Externality – a cost of an activity borne by someone not engaging in the activity. examples: pollution, noise from low-flying aircraft, speeding on a highway, installation of “The Club” in a car External Benefit or Positive Externality – a benefit from an activity realized by someone not engaging in the activity. examples: vaccines, installation of smoke detector in an “attached apartment,” installation of Lojack in a car Note the difference between Lojack and “The Club” If I install Lojack, then a greater fraction of cars have Lojack => “expected surplus” of stealing any arbitrary car is lower => all cars are less likely to be stolen If I use “The Club” => “expected surplus” is lowered for stealing my car but not changed for stealing your car => my car is less likely to be stolen, but your car is more likely to be stolen Market provision of a good for which there is an externality is inefficient: Negative externality => free markets provide more than the optimal amount (i.e., too much) of the good Positive externality => free markets provide less than the optimal amount (i.e., not enough) of the good 13 Market Outcome in Presence of a “Negative Externality”: (?): What is the “best level of pollution” for society? In general, “Marginal Social Cost” is equal to the “sum of Marginal Costs over all people in society” => The sum of “Marginal Private Cost” and “Marginal External Cost” => MSC=MPC+MEC In the presence of a “Negative Externality” there is a “positive Marginal External Cost,” making “Marginal Social Cost” greater than “Marginal Private Cost” (that is, since MEC>0 => MSC>MPC) $ Marginal Social Costs Marginal = MPC = “Supply” Private Costs Marginal Private = MPB = “Demand” Benefits 0 quantity 0 14 If this good was traded in a free, unrestricted, unregulated market => rational, self-interested market participants would base their actions upon “Marginal Private Costs” (and “Marginal Private Benefits”), not taking into account the “Marginal External Cost.” $ Deadweight-Loss Efficient amount of Negative Externality Marginal Social Costs Marginal = MPC = “Supply” Private Costs Marginal Private = MPB = “Demand” Benefits 0 quantity 0 Efficient Level of Trade Free Market Level of Trade Free Market outcome results in “too much of the activity” => positive DWL illustrated by gray area Positive DWL is why “market provision of a good which generates a negative externality is bad”… But note that at the efficient level of trade, there is a positive amount of the negative externality being generated (illustrated by the purple area above) “Best Level of Pollution” for society is NOT ZERO! In order to have “zero pollution” we would have to have: no cars, no electricity, no fire… Clearly the costs of the initial units of pollution are well below the benefits of the initial units of the activities that cause the pollution 15 Potential policies to reduce the DWL associated with a “negative externality” 1. ban the activity entirely (“illegal to emit any pollution”) 2. establish minimum compliance standards for manufacturers (“can only pollute up to a certain level”) 3. “cap and trade” – issue a certain number of “pollution permits” for society as a whole, and allow people to trade these permits amongst themselves 4. offer subsidies to manufacturers that reduce pollution (“pay the polluter to reduce their level of pollution”) 5. charge manufacturers a fee for each unit of pollution emitted (“polluter must pay for the right to pollute”) last three options can most easily implement the efficient market outcome, so long as the “ideal number of permits are issued” or the “subsidy/fee is set appropriately” each of these final three policies attempts to “internalize the externality” by introducing a cost (or foregone gain) that would be realized if the person continues to generate the externality in a similar vein, another solution to the problem of externalities was offered by Nobel Laureate Ronald Coase (1910-; Noble Prize in 1991; Professor Emeritus at Univ. of Chicago Law School) Coase began by explaining that problems of externalities are at their core due to undefined property rights 16 e.g., suppose a new housing development is built right next to McCollum Field here in Kennesaw noisy aircraft impose an external cost on homeowners but, who is causing the externality? (as a parallel, consider the old “Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups” ad: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DJLDF6qZUX0) airport, since they are flying the noisy planes homeowners, since they are living next to the airport as the ad suggests, it takes both parties Should homeowners near the airport have an expectation of “no noise” (i.e., do they have the property right)? Should the airport be able to create all the noise it wants (i.e., does it have the property right)? Coase argued that society must first address this question of who has the property right Coasian Solution to the problem of externalities: i. clearly and fully define property rights ii. make individuals pay compensation if they infringe upon the property rights of others iii. allow parties to negotiate with one another regarding infringements on property rights caused by the externality Coase showed that regardless of which party is given the property right, negotiation between the parties will result in the efficient level of the externality (so long as the costs of negotiation and enforcement are low enough) defining property rights and allowing parties to negotiate essentially “internalizes the externality” 17 “Coasian Solution” in practice: Re-introduction of Wolves in Western U.S. by 1973 the gray wolf did not exist in the wild in Western U.S. re-introduction of wild wolves was supported by environmentalists ranchers opposed re-introduction => concerned about impact of “new predator” on flocks/herds “Coasian Solution” – clearly define property rights, and make people compensate others if property rights are violated ranchers given the “right to have flocks/herds unattacked” “Defenders of Wildlife” (an environmentalist organization) established “The Bailey Wildlife Foundation Wolf Compensation Trust” in 1987 to compensate ranchers for any verified livestock losses due to wolf attacks fund completely financed by private donations => “Our goal is to shift the economic responsibility for wolf recovery away from the individual rancher and toward the millions of people who want to see wolf populations restored.” 2008: 131 payments totaling $226,891 for the killing of 195 cattle, 238 sheep, and 22 other animals Since 1987: 893 payments totaling $1,368,043 for killing of 3,832 animals 18 IV. Lack of Information. market decisions are based upon comparisons of benefits and costs => to make good choices, people must have accurate information about these values for some goods consumers may have difficulty knowing their “true reservation price” => especially common for goods purchased infrequently or for which quality is difficult to observe (e.g., house, car, education, medical procedure, meal at a restaurant). Further note, “information” is often a “club good” (non-rival in consumption and excludable). Once a club good is produced, the additional cost of providing it to the next person is essentially zero => to maximize social surplus, everyone who has a positive value for the information should be able to access it Additionally, as long as the information is accurate, total costs to society are minimized if the information is only generated once (e.g., it is a waste of resources to have both the National Weather Service and AccuWeather come up with weather forecasts) In such cases, have government license, inspect, and/or regulate providers of such goods in order to: i. provide people with the important information needed to make good decisions in markets and ii. minimize the costs to society of providing the information e.g., “Cobb and Douglas Public Health” inspects restaurants and assigns letter grades based upon compliance with health codes => government “regulates product” and “provides information” 19