Computer forensics Sanitizing Old Computers

advertisement

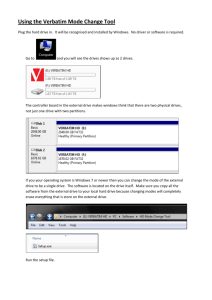

Back to Fraud Information Articles © November/December 2005 Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Computer forensics Sanitizing Old Computers B y R i c h a r d D . C a n n o n , C F E , C F C E From the November/December 2005 issue of Fraud Magazine In an age when government agencies and private companies are striving to keep up with current technology, old computers are being sold or recycled to recoup some of the cost associated with upgrading. Does your office "clean" the hard drives before the systems are recycled? How effective is the process they use? A n AP news story out of Helena, Montana, reported in May that the Montana legislative auditor announced that several state agencies had sent to surplus a large number of computers without ensuring that their hard drives' data had been destroyed. Most of these computers were destined to be sent to Montana public schools but some were to be sold to the public or transferred to other state agencies. Unclear state policy was blamed as the cause of this risk to confidential information. How clean is clean? Computers can store vast amounts of data. Hard drives are constantly increasing in size and speed. With technology changing almost daily, computers purchased more than two years ago are approaching "door stop" status. Companies and government agencies, which struggle to replace outdated equipment, are faced with the decision of how to remove the data on outgoing machines. Some entities have opted to needlessly destroy drives altogether rather than spend the time to properly sanitize them. What does your organization do? Are they re-formatting the drives, using a wiping program, destroying the hard drives, or simply denying the threat and choosing to do nothing? Simply reformatting or even repartitioning the drives and sending them out the door isn't much more effective than doing nothing. Fraudsters can use common commercial programs to recover reformatted and even repartitioned hard drives. So what does the formatting process actually do? Low-level and high-level formatting The manufacturer of a hard drive will conduct a low-level formatting or initializing to create the physical tracks and sectors on the hard drive's "platters," which allows it to record data. (The platters are the actual disks inside the drive that store the magnetized data.) The low-level format normally never needs to be performed again on a hard drive. A high-level format, on the other hand, is what we typically refer to when we use the term format. A hard drive is generally divided into regions. Some regions aren't made available for the user and are reserved for use by the system. Other regions contain the user's data. Here the user can easily read and write data with few restrictions. Let's say you want to reformat digital media such as a floppy disk. (While floppy disks are becoming a thing of the past, most of us remember when formatting a floppy was a regular occurrence and are a good representation of the format process.) You have two format options: "Quick Format" or an "Unconditional Format." In the Quick Format the "data area" of the disk isn't touched, which means that the files you may have wanted to erase actually still exist. Your computer's operating system just doesn't have a way to find them now. The File Allocation Table (FAT) on both the floppy and your computer keeps track of where all the files on the floppy are located. The FAT is similar to a library card catalog for the hard drive. At the library you search in the card catalog for the listing of your book, which tells you where it is located in the stacks. The FAT tells the computer where to locate the file (on the floppy or the hard drive) once you decide to access it. (In the New Technology File System [NTFS] available with Windows NT, 2000, and XP the Master File Table [MFT] carries out a similar function to that of FAT.) During the Quick Format, the hard drive or floppy's "card catalog" is "zeroed out" or cleaned and the root directory or table of contents is overwritten (or replaced with a ready-to-use clean slate) so that it can store new file names but nothing happens to the files and subdirectories that the disk contained. After a Quick Format, the data area remains untouched. All the data can still be recovered, with the exception of the root directory file names, even though the typical user is no longer able to access the files. On the other hand, Unconditional Format overwrites all the data area on the floppy so that none of the data is recoverable. Unfortunately, the Unconditional Format only works with floppies and not hard drives. So if you're reselling your computer or trading up and diligently trying to protect yourself by reformatting the drive with Quick Format, you've done little more than place all your important papers in a trash bag and set it out by the curb; you're safe as long as no one tries to open the bag and remove the contents. The NTFS file system commonly found in Microsoft's Windows 2000 and XP installations can provide an additional layer of security through its optional encryption features, which will make it more difficult but not impossible to recover the data. The NTFS file system is more sophisticated than FAT. NTFS without encryption, however, is little different than the FAT file system when it comes to the ability to recover data after formatting. When simply formatting a hard drive the contents of the drive are still retrievable. Wiping programs You can truly wipe or sanitize portions or all of a hard drive with one of the several commercially available products designed for just that purpose. Products vary widely in the wiping speed and methods depending on the types of data you want cleaned and the speed of your computer's processor. Some programs overwrite the drive in patterns that don't completely remove data but make it very difficult if not impossible to recover files. Other programs completely overwrite every byte on the drive and then overwrite those areas several more times so that it's impossible to recover with conventional means. The U.S. Department of Defense has issued a data clearing standard (DOD 5220.22-M) that requires all data on a hard drive to be overwritten at least seven times to ensure that the data can't be recovered. (Peter Gutman, a computer engineer, created an algorithm for a program that overwrites data 27 times.) Wiping programs offer several options from a one-pass wipe to a multi-pass wipe. Make sure you can verify a wiping program's claims. Someone who knows digital forensic analysis should verify that the data actually is unrecoverable by analyzing a piece of sample media that has been subjected to a particular wiping process. I've analyzed several computers whose suspect owners assumed their wiping programs deleted all the evidence they were trying to destroy. Unfortunately, for them, they failed to verify the process and we were still able to retrieve some evidence to use in the investigation. Most computer technicians don't dispute the wiping programs' claims of effectiveness but object to the effort and time they take. Many simple wiping programs function at the DOS level in which the program can gain complete access to the hard drive's sectors. Other programs that function in the Graphical User Interface (GUI), such as in Windows, might not have complete access to all the drive's sectors. In some cases this may be sufficient. The wiping process can take some time depending on the drive's size. It can take additional time to confirm through the program's verification process that the wipe was successful. It's because of this extra effort that IT departments often remove the drives and physically destroy them. Of course, you have to give your computers to a third party to destroy the drives and hope that the company actually does that. (But that's another story!) Depending on whose survey you read, 50 percent to 80 percent of the second-hand hard drives purchased through popular Internet auction sites contain data that can be recovered. It has been said that the only truly safe data is located on a hard drive encased in concrete and left at the bottom of the ocean! Of course, we don't need to go to that extreme to protect the data on systems that we recycle. While it may be time consuming to destroy this data it's important to do so. There are plenty of crooks out there who would love to get their hands on that data. Why make it easy for them? Richard D. Cannon, CFE, CFCE, is the forensic technology director for the ACFE. His e-mail address is: rcannon@ACFE.com. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners assumes sole copyright of any article published in Fraud Magazine. Fraud Magazine follows a policy of exclusive publication. Permission of the publisher is required before an article can be copied or reproduced. Requests for reprinting an article in any form must be e-mailed to: FraudMagazine@ACFE.com.