Hedging

advertisement

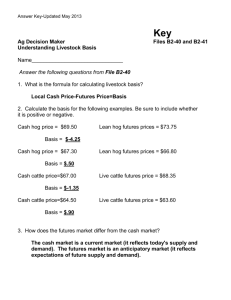

Hedging Hedging Hedging in the futures market can be an important component in a producer’s price risk management toolbox. However, even for producers who never hedge directly in the futures market, understanding the mechanics behind a futures hedge, and how to calculate the expected net selling or buying price resulting from a hedge can be important information in analyzing the quality of any cash market selling or buying opportunity. A futures market hedge involves taking a position in the futures market as a temporary substitute for a transaction that will occur in the cash market at a later date. As long as the futures and cash markets move together, any loss in one market will be offset by a gain in the other market, and the net transaction price incurred at the end of the hedge period will equal the price that was expected when the hedge was set. The key element in arriving at an accurate cash price expectation resulting from a futures market hedge is having an accurate basis forecast. Hedging is essentially the trading of price risk for basis risk. The more accurately the basis is forecast, the closer the final transactions price will be to the price anticipated when the hedge was placed. Short Hedge or Hedging a sales price A producer who expects to sell something in the cash market later can protect the future cash market price by selling a futures contract for the identical commodity now. This is also called as a short hedge. When the initial trade is the sale of a futures contract, the seller is said to be “short”, in the market. The seller has sold a commitment to make delivery of a commodity. For example, if a producer expects to sell corn next November, he/she could sell a December1 corn futures contract. Each contract is for 5000 bushels of corn,2 so in many cases a futures hedge will not correspond to the exact same number of bushels that are to be sold in the cash market. Once a futures hedge has been initiated, the producer has exchanged market price risk for basis risk. Recall from Chapter 2 that basis risk is the risk that the futures and cash prices do not end up with the same relationship that was initially anticipated. If the basis ends up weaker than expected (i.e., the cash price is lower relative to futures than anticipated), the producer’s actual net selling price will be lower than thought when the hedge was initiated. If the basis is stronger than expected (cash price higher relative to futures than initially anticipated), the net selling price will be higher than originally thought. The only thing that can affect the final outcome of a hedged position is a change in basis relative to expected basis. 1 For most commodities, there are not futures contracts for delivery every month. In grain markets, producers should hedge with the futures contract that specifies delivery as close to, but after, the cash transaction is expected to take place. There is a November corn contract, but it will expire before the end of November, thus the December contract would be the best choice to hedge a November cash sale. 2 There are also contracts for corn (and other grains) in 1000-bushel amounts traded at the Mid-American Futures Exchange in Chicago. They can be used for hedging, but most futures brokers do not discount their commissions for the smaller volume contracts, so per bushel transactions costs tend to be higher than with the full size contracts. Grain Marketing Page 1 Hedging Assume it is May 1, and a grain producer is considering hedging 15,000 bushels of soybeans for October delivery; i.e., the producer wants to deliver soybeans into the cash market at harvest, but wants to lock in the harvest price in May (recall that 5000 bushels is equal to one futures contract). To calculate the expected price from the hedged position, the producer must note the current futures price for the November soybean futures contract.3 This futures price must then be "localized", or translated into an expected local cash price. This is done by adjusting the futures price by the basis. The relevant basis is the one the producer thinks will exist in October (i.e., the October cash soybean price minus the November soybean futures contract price), not the basis which exists on May 1. If the producer has paid close attention to previous years’ basis relationships in the October delivery period, he/she will be in a position to derive an accurate estimate of the expected price resulting from a hedge for October delivery of soybeans. Suppose on May 1 the November soybean futures contract is trading for $6.50 per bushel. Based on pervious experience, the producer expects basis in October to be minus $0.40. In other words the producer’s cash soybean price in October is expected to be $0.40 below the November soybean futures price in October. The producer would expect to receive a selling price of $6.10 per bushel soybeans in October if a hedge were initiated on May 1. This comes from a May 1 futures price for November soybeans of $6.50 localized by the negative $0.40 basis. However, to initiate a hedge the producer must work with a futures broker. The producer will have to pay the broker a commission to initiate the futures position, and deposit the initial margin required for the position in a futures trading account (recall the discussion of futures margins from Chapter 1). Assume the commission is $50 per contract, or $0.01 per bushel for a 5000-bushel contract. Then the net price the producer expects to receive for cash soybeans in October is $6.09 per bushel. This comes from adjusting the expected cash price of $6.10 per bushel for the 1 cent per bushel broker’s commission. As long as the basis forecast is accurate, the producer can be confident he/she will receive $6.09 per bushel regardless of what happens to soybean prices between May and October. Example 1 illustrates the hedge described above. Note the producer nets $6.09 per bushel for soybeans in October regardless of whether prices rise or fall over the hedge period. This is based on the assumption that the basis expectation is realized at the end of the hedge period. In other words there is no change in basis i.e. the basis remained constant from the time the hedge was initiated to the time that the hedge was lifted. 3 This is the soybean futures contract that expires closest to, but after the expected cash sale date. Grain Marketing Page 2 Hedging Example 1. Short Hedge or Hedging a Sales Price. Assume it is May 1, and a grain farmer wants to protect the price received for October harvested soybeans. November soybean futures contracts are trading for $6.50 per bushel. The farmer would hedge harvest soybean prices by selling November futures on May 1. Adjusting the May 1 futures price for the expected basis in October, and the futures broker’s commission derive the expected cash price in October. Date Futures Market Cash Market Basis May 1 Grain farmer sells 3 November soybean futures contracts Establishes an expected October selling price of $6.50 + (-$0.40) - $.015 (Futures + Basis - Comm.) = $6.09 Expected to be $6.50 -$0.40 Scenario 1. Perfect Hedge (Declining prices): Assume the November futures contract is $5.50 when the cash sale is made in October, and basis turns out as expected. The producer sells the cash soybeans for $5.10 per bushel (futures is $5.50 and the basis is -$0.40). He then buys the November futures contract he sold on May 1 back for $5.50 per bushel. The basis was accurately forecast, and his net selling price is as expected. Date Futures Market Cash Market October Grain farmer buys 3 November futures contracts for $5.50 per bushel. Sells 15,000 bushels of soybeans to the local coop Sold on May 1 $6.50 Bought on Oct. 1 $5.50 +Cash price $5.10 Futures profit +$ 0.99 ------- Futures profit $1.00/bu. Broker’s comm. - $0.01//bu -----Net Futures Profit $0.99/bu. Basis -$0.40 (No change in basis) Net Selling Price $6.09 The combination of a cash price of $5.10/bu. plus a futures profit of $0.99/ bushel. nets the grain producer an effective soybean price of $6.09/bu., which is what was expected. This is a perfect Grain Marketing Page 3 Hedging hedge because the expected basis is same as the final basis. The basis remained constant. Observe that the hedge gave protection from downside price risk. Scenario 2. Perfect Hedge (Raising prices): Assume the November futures contract is $7.50 when the cash sale is made in October, and basis turns out as expected. The producer sells the cash soybeans for $7.10 per bushel (futures is $7.50 and the basis is -$0.40). He then buys the November futures contract he sold on May 1 back for $7.50 per bushel. The basis was accurately forecast, and his net selling price is as expected. Date Futures Market Cash Market Basis October Grain farmer buys 3 November futures contracts for $5.50 per bushel. Sells 15,000 bushels of soybeans to the local coop Sold on May 1 $6.50 Bought on Oct. 1 $7.50 +Cash price Futures loss -$0.40 $7.10 -$ 1.01 ------- (No change in basis) Futures loss $1.00/bu. Broker’s comm. - $0.01//bu -----Net Futures Loss -$1.01/bu. Net Selling Price $6.09 The combination of a cash price of $7.50/bu. minus a futures loss of $1.01 nets the grain producer an effective soybean price of $6.09 /bushel, which is what was expected. Observe that there is no change in the basis estimated and the final basis. Also realize that in the case of rising prices the hedge prevented the farmer from taking advantage of rising prices. Grain Marketing Page 4 Hedging Scenario 3. Imperfect Hedge (Basis risk: Weakening basis): This is the same as scenario 1, except in this case the basis turns out to be weaker than expected by $0.10/bu. A weaker basis means that the cash price is lower relative to futures than had been expected. The expected basis is minus $0.10 where as the actual basis is minus $0.50. If the basis is weaker by 10 cents, the cash price is 10 cents lower than would have been the case if the basis forecast had been correct. Date Futures Market Cash Market October Grain farmer buys 3 November futures contracts for $5.50 per bushel. Sells 15,000 bushels of soybeans to the local coop Sold on May 1 $6.50 Bought on Oct. 1 $5.50 +Cash price $5.00 Futures profit +$ 0.99 ------- Basis -$0.50 (10 cents weaker than expected) Futures profit $1.00/bu. Broker’s comm.- $0.01//bu -----Net Futures Profit $0.99/bu. Net Selling Price $5.99 While the futures hedge did protect the cash position from most of the price decline, the unexpected weakening of the basis did result in a lower net sales price than originally anticipated. Observe that even though this hedge was able to prevent the price risk but there was basis risk. For a short hedger weakening basis results in lower net selling price. Grain Marketing Page 5 Hedging Scenario 4. Imperfect Hedge (Basis risk: Strengthening basis): This is similar to scenario 3, except that the basis ends up stronger than expected. A stronger than expected basis means that the cash price is higher relative to the soybean futures price than had been originally anticipated. Date Futures Market Cash Market November 1997 Grain farmer buys 3 November futures contracts for $5.50 per bushel. Sells 15,000 bushels of soybeans to the local coop Basis -$0.30 Sold on May 1 $6.50 Bought on Oct. 1 $5.50 Futures profit $1.00/bu. Broker’s comm.- $0.01//bu -----Net Futures Profit $0.99/bu. +Cash price $5.20 Futures profit +$ 0.99 ------- (10 cents stronger than expected) Net Selling Price $6.19 This time the producer ends up better off then expected as the result of a stronger basis. Futures prices over the hedge period fell by more than cash prices resulting in a stronger than expected cash market. In the case of rising prices (such as in scenario 2), cash price would have to raise more than futures prices for the basis to strengthen. For a short hedger strengthening basis results in higher net selling price. Conclusion The net selling price of a hedged cash commodity will not change regardless of whether prices rise or fall over the hedge period as long as the basis is accurately forecast. Once a commodity is hedged, price risk has been traded for basis risk. It is critical to have as accurate an expectation of basis as possible in order to minimize the possibility of receiving a net selling price that is less than the expected selling price. Grain Marketing Page 6 Hedging In scenario 3 and 4 where there is basis risk and the outcome (net selling price) differed from that of perfect hedge scenarios given in 1 and 2. Scenarios 3 and 4 in example 1 show what happens to a hedged position when the basis forecast is wrong. If the basis turns out to be weaker than expected,4 the producer will get a lower net selling price than originally anticipated (scenario 3). However, if the basis turns out to be stronger than expected, the producer will get a higher price than anticipated when the hedge was placed (scenario 4). Scenarios 3 and 4 illustrate the need for accurate basis forecasts in developing a Successful hedging program. Recall that a hedge effectively trades price risk for basis risk. As long as changes in basis levels are smaller than changes in price levels, a hedge contains less market risk than an un-hedged position. However, to absolutely minimize market risk it is critical to accurately anticipate the basis. A template for calculating the expected return from a selling hedge is presented in table 1. All costs incurred in facilitating the hedge activity result in decreasing the effective price received by the seller for the final commodity. To compute the estimated price of a commodity protected through a hedge, the hedger takes the futures price, adjusts it for the basis, and then subtracts the futures broker’s commission. Table 1. Template for Calculating Expected Net Selling Price from a Short Hedge. Futures Price _________________ + Expected Basis _________________ - Brokers Commission __________________ __________________________________________ = Expected Net Selling Price __________________________________________ 4 A weaker than expected basis would occur if the cash price is lower relative to futures than originally anticipated. A stronger than expected basis is one in which the cash price is higher relative to the futures price than was anticipated. For example, if a producer expects the basis to be +$1.40 (meaning the cash price will be $1.40 above the futures price at the end of the hedge period), but the basis is actually +$1.35, the basis is 5 cents weaker than expected. If the cash price turns out to be more than $1.40 above the futures price then the basis is stronger than expected. Grain Marketing Page 7 Hedging Trading Mechanics: In addition to accurate basis expectations, a successful hedger must be able to finance the futures part of the hedge over the hedge period. Futures contracts are traded on margin. This means both buyers and sellers of futures contracts must post an amount of money with their futures broker as an insurance bond against defaulting on any loses that may be generated in the futures account. This deposit is called as initial margin. For the example here, the total value of the futures contracts when the hedge is placed in September is $97,500 ($6.50 per bushel * 5000 per contract * 3 contracts). Margins vary by broker and market conditions, and hedgers usually have lower initial margin requirements than futures speculators. For the example above, assume the producer must post $1000 initial margin for each futures contract sold. The total initial margin would be $3000. Even though the hedger is a seller, a margin account must be maintained. The sales price being established through the hedged position will not be realized until the soybeans are sold in the cash market and the futures position eliminated. In the meantime, however, prices will change and this has implications for the hedger’s futures trading account. Futures contracts are marked to market daily. This means that all futures profits and losses must be settled each day. This is what causes margin calls, or the requirement for futures traders to add to their futures margin account when prices move against their position. For a hedger who has sold futures contracts, margin calls result when the futures prices move above the price at which the hedger sold. If a hedger were to exit the futures market at a price above the initial selling price, he/she would buy the futures contract back at a price higher than it was sold for, and generate a financial loss. To insure against a default on a potential futures loss, hedgers who sold futures before a price rise would need to deposit additional money in their futures margin account in order to keep their hedged position. The margin call simply brings the value of their performance bond back to the initial margin level. Usually a small loss is allowed before a margin call occurs. The point at which a margin call is initiated is called the maintenance margin. Once the value of the hedgers futures account reaches the maintenance margin, an additional deposit must be made to the futures account to bring its value back to the initial margin or the futures position cannot be maintained. For this example, assume the maintenance margin is $750 per contract. The hedger’s futures position could then deteriorate by a total of $250 (or 5 cents per bushel) before an additional deposit to the futures account would be required. For a hedger, a margin call during the hedge period should not be considered a loss since it is associated with a more valuable cash commodity, and the net expected selling price at the end of the hedge period has not changed. However, it can still create cash flow problems if the hedger is not sufficiently capitalized to make the margin calls before the cash commodity is ready for sale. One solution to this problem is to work with an agricultural lender who can provide a line of credit to facilitate the hedge activity. While all lenders do not provide this service, many realize that it is in their best interest to have the price of a commodity whose proceeds will be Grain Marketing Page 8 Hedging used to service a production or business loan protected against adverse price movements, and they are willing to help customers with hedging programs. Under most circumstances, a hedger who sold futures contracts initially would buy those contracts back before the contracts expire in order to offset the hedged position. Grain contracts require physical delivery at contract expiration, thus any hedger who did not buy back a futures hedge would be required to deliver soybeans against a futures contract sale. However, the soybeans would have to have already been graded and certified for delivery against a futures contract commitment, meaning a producer could not simply deliver the cash soybeans her or she was growing into the futures market. Majority of the contracts in the market will be closed out prior to the actual delivery dates by taking offsetting positions. Only few contracts will be delivered in accordance with the delivery process. Long Hedge or Hedging a Purchase Price The mechanics of hedging a commodity to be purchased in the cash market at a later date are similar to the sales hedge described above. The one difference is that a purchase hedge is initiated by buying a futures contract. This is also called as a long hedge. When the initial trade is the purchase of a futures contract, the seller is said to be “long”, in the market. The seller has sold a commitment to take delivery of a commodity. As prices rise, the cash commodity to be purchased later is becoming more expensive, but futures prices are also rising, generating a profit in the futures position. This profit is used to offset the increased price of the cash commodity, and, if basis has been forecast accurately, the net purchase price originally established by the hedge becomes the effective price paid for the cash commodity. Assume it is November 1 and a dairy producer would like to lock in a purchase price for 15,000 bushels of corn to be bought in June and used as feed next summer. By hedging in a specific corn futures contract month, a dairy farmer effectively locks in the price he/she will pay for corn for the summer feeding period. In the example here, the farmer can hedge 15,000 bushels of corn to be bought in the cash market in June by buying 3 July corn futures contracts (i.e., contracts for the delivery of corn next July). The important information for the farmer is the current futures price for July delivery, and the expected basis in June (i.e., the difference between the June cash corn price July futures price in June). The purchase price hedge is illustrated in example 2. It considers the four scenarios covered in the selling hedge. Again, as long as the producer has accurately forecast the June basis, the hedged purchase price will be realized whether corn prices move up or down over the hedge period. The only thing that will affect the actual purchase price relative to the expected price established by the hedge is a basis that differs from the expected basis. Grain Marketing Page 9 Hedging Example 2. Long Hedge or Hedging a Purchase Price. Assume it is November 1 and a dairy farmer wants to lock in the purchase price for 15,000 bushels of corn to be bought in June. The farmer would need to purchase 3 July corn contracts to hedge June corn purchases. The expected basis in June is $0.15 under July contract. The expected June purchase price is derived by adjusting the July futures price traded on November 1 for the expected basis in June and the futures broker’s commission. Date Futures Market Cash Market Basis Nov 1 Dairy farmer buys July corn contracts Establishes an expected June purchase price of $2.10 -$0.15 + $.01 (Futures + Basis + Comm.) $2.36 Expected to be $2.50 Grain Marketing -$0.15 Page 10 Hedging Scenario 1. Perfect Hedge (Raising prices): Assume the July futures corn futures price is $3.50 per bushel when cash corn is purchased in June, and the basis turns out as expected. The producer buys cash soybeans for $3.35 per bushel (futures is $3.50 and the basis is -$0.15). He then sells the July futures contract he bought on November 1 for $2.50 per bushel. The basis was accurately forecast and his net purchase price was as expected. Date Futures Market Cash Market June Dairy farmer sells 3 July corn futures contracts for $3.50per bushel. Buys 15,000 bushels of corn from a local coop Bought on Nov 1 $2.50 Sold on June 1 $3.50 $10.50 Futures profit Broker’s comm. $1.00 - $0.01 -----Net Futures profit $0.99 Cash price $3.35 Futures profit -$ 0.99 ------- Basis -$0.15 (No change in basis) Net Purchase Price $2.36 Note that the futures profit is subtracted from, and the broker’s commission added to the net buying price of the dairy farmer. These items affect the farmer’s net corn purchase price. The combination of a cash price of $3.35/bu. minus a futures profit of $0.99 nets the dairy producer an effective corn price of $2.36 /but, which is what was expected. Grain Marketing Page 11 Hedging Scenario 2. Perfect Hedge (Declining prices): Assume the July futures corn futures price is $1.50 per bushel when cash corn is purchased in June, and the basis turns out as expected. The producer buys cash soybeans for $1.35 per bushel (futures is $1.50 and the basis is -$0.15). He then sells the July futures contract he bought on November 1 for $2.50 per bushel. The basis was accurately forecast and his net purchase price was as expected. Date Futures Market Cash Market November 1997 (futures) Dairy farmer sells 3 July corn futures contracts for $1.50 per bushel. Buys 15,000 bushels of corn from a local coop January 1998 (cash) Bought on Nov 1 $2.50 Sold on June 1 $1.50 Futures loss $1.00 Broker’s comm. + $0.01 -----Net Futures loss $1.01 Cash price Futures loss Basis $1.35 +$1.01 ------- -$0.15 (No change in basis) Net Purchase Price $2.36 The combination of a cash price of $1.50/bu. plus a futures loss of $1.01 nets the dairy farmer an effective corn purchase price of $2.36 /bushel, which is what was expected. Grain Marketing Page 12 Hedging Scenario 3. Imperfect Hedge (Basis risk: Weakening basis): This is the same as scenario 1, except in this case the basis turns out to be weaker than expected by $0.10/bu. A weaker basis means that the cash price is lower relative to futures than had been expected. If the basis is weaker by 10 cents, the cash price is 10 cents lower than would have been the case if the basis forecast had been correct. Date Futures Market Cash Market November 1997 (futures) Dairy farmer sells 3 July corn futures contracts for $3.50per bushel. Buys 15,000 bushels of corn from a local coop Bought on Nov 1 $2.50 January $3.50 1998 (cash) Sold on June 1 Cash price $3.25 Futures profit -$ 0.99 ------- Basis -$0.25 (10 cents weaker than expected) Futures profit Broker’s comm. $1.00 - $0.01 -----Net Purchase Price $2.26 Net Futures profit $0.99 While the futures hedge offset the increase in cash prices, the unexpected weakening of the basis did result in a lower net purchase price than originally anticipated. For a long hedger weakening basis gives a better net buying or purchase price. Grain Marketing Page 13 Hedging Scenario 4. Imperfect Hedge (Basis risk: Strengthening basis): This is similar to scenario 3, except that the basis ends up stronger than expected by $0.10 /bushel. A stronger than expected basis means that the cash price is higher relative to futures than had been originally anticipated. Date Futures Market Cash Market November 1997 (futures) Dairy farmer sells 3 July corn futures contracts for $3.50per bushel. Buys 15,000 bushels of corn from a local coop Bought on Nov 1 $2.50 January $3.50 1998 (cash) Sold on June 1 $1.00 - $0.01 -----Net Futures profit $0.99 Cash price $3.45 Futures profit -$ 0.99 ------- Futures profit Broker’s comm. Basis -$0.050 (10 cents stronger than expected) Net Purchase Price $2.46 This time the dairy farmer ends up worse off then expected as the result of a stronger basis. Futures prices over the hedge period rose by less than cash prices resulting in a stronger than expected cash market. This leads to a higher net purchase price than originally anticipated. For a long hedger strengthening basis gives a worse net buying price. Conclusion The net purchase price of a hedged cash commodity will not change regardless of whether prices rise or fall over the hedge period as long as the basis is accurately forecast. Once a commodity is hedged, price risk has been traded for basis risk. It is critical to have as accurate an expectation of basis as possible in order to minimize the possibility of incurring a net purchase price that is greater than the expected purchase price. Grain Marketing Page 14 Hedging Calculating the expected return from a buyer’s hedge is slightly different than the calculations for a selling hedge. Any costs incurred in facilitating the hedge activity results in increasing the effective price paid by the buyer for the final commodity. To compute the estimated purchase price of a commodity protected through a hedge, the hedger takes the futures price, adjusts it for the basis, and then adds the futures broker’s commission. A template for calculating the expected net buying price from a hedged position is presented in table 2. Table 1. Template for Calculating Expected Net Purchase Price from a Long Hedge. Futures Price _________________ + Expected Basis _________________ + Brokers Commission __________________ __________________________________________ = Expected Net Selling Price __________________________________________ Just like the selling hedge, a purchase hedge requires an initial deposit in a futures trading account, and the account must be maintained as the futures positions are marked to market. The difference is that margin calls for a buyer occur as prices drop, because the value of the buyer’s futures position is decreasing. However, this should not be viewed as a financial loss because falling prices mean the cash commodity that will eventually be bought is also decreasing in value, and the net purchase price that was established with the hedge is being maintained. Unlike the seller’s hedge, a stronger then expected basis results in a less favorable outcome than anticipated by the corn buyer, while a weaker basis improves the buyer’s market position. A stronger than expected basis means that the cash price paid by the dairy farmer is higher relative to futures than had been expected. A weaker basis means the buyer’s price is less relative to the corn futures price than had been initially expected. Grain Marketing Page 15 Hedging Ten Don’ts in Hedging 1) Don’t enter the futures market until you understand how to use it. 2) Don’t ask your broker to make management decisions for you. 3) Don’t combine hedging and speculating. 4) Don’t hedge unless you “know” your “basis”. 5) Don’t hedge if you can’t meet additional margin calls. 6) Don’t view futures markets as an outlet for delivery of your crop. 7) Don’t think of futures markets as a way to get higher prices. 8) Don’t lift your hedge before you buy or sell your commodity in the cash market. 9) Don’t forget that hedging insulates you from subsequent major price changes – both downward and upward. 10) Don’t expect hedging to be panacea for poor management. Grain Marketing Page 16 Hedging Basis Records: It is vital to keep proper basis records for a successful hedging program. You should develop worksheets to record the basis information for the markets that you use to market the commodity and also the appropriate futures months. Following is an example of worksheet that records the corn cash prices, July futures price and basis for the mid day of the week (Wednesday). An Example of Corn Basis Records Date (Wednesday of the week) Cash Price July Futures Closing Price Basis 1-5 $3.17 $3.27 -10 1-12 $3.22 $3.37 -15 1-19 $3.14 $3.29 -15 1-26 $3.20 $3.31 -11 2-2 $3.21 $3.35 -14 2-9 $3.16 $3.32 -16 2-16 $3.11 $3.34 -13 2-23 $3.16 $3.26 -10 3-1 3-8 Grain Marketing Page 17 Hedging Exercises Exercise 1: Futures Contracts Develop an understanding of the mechanics of futures contracts Learn how the futures and cash markets interact Discover how selling below and above the futures contract price affects the net price During March, 2002 you sell a December futures contract for soybeans at $5.10. You close out the contract in December and sell cash beans at the Grainville Elevator in the same month. The CBOT price at the time is $4.80. The local December basis is $0.30. Calculate your net price on the soybeans. Calculate the net price received for the beans if the CBOT price is $5.40 at the time you close the contract and sell the beans. Grain Marketing Page 18 Hedging Exercise 2: Futures Contracts Learn how futures contracts and local basis interact to create marketing opportunities Learn how to calculate net selling price Assume that in August when his crop looks quite favorable, a farmer observes that the futures market is offering $3.25 per bushel for December delivery of corn. He knows from the historical basis records that he kept the basis is 10 cents under the December futures contract. He lifts the hedge November when the December futures are trading at $3.10. Question: By hedging in the December futures at what price he can lock in if there is no basis risk? What is the final net selling price if the basis at the time of actual sale is minus 20 cents? Grain Marketing Page 19 Hedging Exercise 3: Futures Contracts Discover the risks that are incurred when cash sales are disconnected from the corresponding futures positions You have 3,000 bushels of soybeans to market. You sell a futures contract for March beans (see CBOT price data sheet). You close the contract and sell cash beans in late February at Grainville Elevator. The CBOT price at the time is $5.41. Using the Grainville basis calculated in Exercise 1, what price did you net on the beans? The market looks very strong in February when you close out your futures position ($5.41). You decide to hold onto the beans. You end up selling them to Grainville Elevator in June when the CBOT price is $5.02. What price did you net on your beans? Grain Marketing Page 20