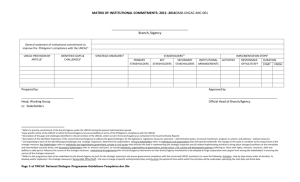

Improving the Consistency of Palestinian Security Sector Legislation with

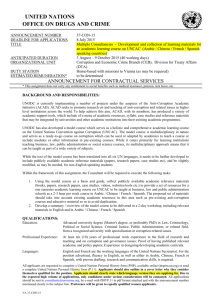

advertisement