CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE BASIC MOUNTAINEERING:

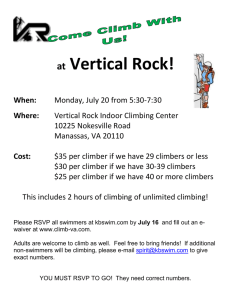

advertisement

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE

BASIC MOUNTAINEERING:

11

A TEACHING GUIDE

A graduate project submitted in partial satisfaction of

the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in

Recreation and Leisure Studies

by

Paul Arnold

~llweg

June 1980

The Graduate Project of Paul Arnold Hellweg is approved:

California State University, Northridge

ii

DEDICATION

This graduate project is dedicated to

Mr. &Mrs. Robert D. Hellweg

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I wish to thank the many friends and co 11 eagues who cant ri buted

to this graduate project.

To begin with, the members of my Graduate

Committee -- Talmage W. Morash, George E. Welton, and John J. Bullaro

-- provided valuable support and guidance.

their assistance,

I thus wish to acknowledge

Also of great value to me was the technical

expertise provided by Mr. Sid Mountain.

Much of this project is an

attempt to formalize the rock climbing teaching techniques pioneered

by Mr. Mountain.

Three of the accompanying slides were taken by Jack Roberts

(Slide Set I, slides 1, 8, and 10).

All other slides are by myself,

but they were taken with the assistance of the following persons:

Steve Reichlin, John Anderson, Don Fisher, Gail Jarvis, Jay Sanzo,

Cindy Lee, Colleen Rooney, Eleanor Bianchi, Annie Larson, Scott

Bullock, Dave Lime, and Pat Witt.

The slide sets would not have

been possible without their assistance.

Finally, special thanks to Kathy Seacord for her editorial and

secretarial assistance, and to my parents for their love and support.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Dedication

iii

Acknowledgements

iv

Table of Contents

v

Abstract

vi

Introduction

1

Course Outline

5

List of Class Equipment

6

Lesson Plans

7

Narrative, Set I

44

Narrative, Set II

57

Bibliography

69

v

ABSTRACT

BASIC MOUNTAINEERING

A TEACHING GUIDE

by

Paul Arnold Hellweg

Master of Science in Recreation and Leisure Studies

This project provides a complete set of lesson plans and training

aids for the teaching of a university-level course in Basic Mountaineering.

The justification for this project is that it facilitates

the teaching process for a qualified mountaineering instructor who

lacks the organizational skills of the professional educator.

Central to this project are two slide sets with accompanying

narratives.

The slides present the fundamentals of climbing in a

concise, visual, easy-to-understand fonnat.

Subject matter starts

with basics and then proceeds to more advanced techniques.

The

slides thus present an overview of the entire semester and should

be used as introductory lectures.

vi

In addition to the slide sets, this project provides an entire

set of lesson plans for the teaching of a semester long course.

The

lesson plans provide guidance for the instructor by describing the

equipment required, the safety considerations, and the behavioral

objectives for each class.

For classroom sessions, the lesson plans

provide a detailed outline of contents.

For field sessions, each

lesson plan not only describes the type of activity to be conducted

but also gives criteria for selecting an appropriate climbing route.

The lesson plans and accompanying slides form the heart of this

project, but some additional materials are provided.

the following:

These include

an introduction, a sample course outline, a list of

all required equipment, and a bibliography.

In summary, this project

provides complete background material for the teaching of Basic

Mountaineering.

vii

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this project is to compile, in a logically

ordered format, all the material necessary to teach a universitylevel class in Basic Mountaineering.

the following minimum requirements:

The class instructor must meet

ability to lead climbs sub-

stantially harder than anything the class will be attempting;

demonstrated outdoor leadership experience; demonstrated mature

judgment; demonstrated safety consciousness; and, knowledge of

advanced first-aid procedures.

Preferably, the instructor should

also have university teaching experience.

It may not be possible,

however, to find a qualified instructor with both the requisite

climbing experience and teaching experience.

justification for this project.

Therein lies the

The intent is to facilitate the

instructional process for an otherwise qualified instructor who

lacks the organizational skills of the teaching professional.

To

this end, complete lesson plans and training aids have been provided

for the teaching of an entire semester length course.

This project presupposes a Basic Mountaineering Class of 15

weeks (one academic semester), meeting once weekly for a period of

two or more hours, and conducted at a university with a readily

accessible climbing area.

If no climbing area is available locally,

1

2

the same lesson plans are nonetheless applicable.

The only change

is that the weekly two hour climbing sessions would have to be

combined into one or more weekend climbing periods.

HOW TO USE THIS PROJECT

The new instructor should first become familiar with the lesson

plans in order to gain an understanding of how the class is structured.

Next, the slides and accompanying narrative should be

thoroughly studied before presentation.

Once all course materials

have been reviewed, the instructor should determine which portions

are applicable to the specific situation.

It is not intended that

the instructor adhere strictly to the materials provided -- available

time, weather, climbing facilities, instructor•s prerogative and

related variables are likely to effect the structuring of any course.

It is intended, however, that the accompanying materials provide

the new instructor with understanding(s) of an appropriate approach

to the teaching of mountaineering.

The lesson plans emphasize

attention to detail and safety consciousness throughout.

Addition-

ally, the lesson plans are presented in a manner such that they

provide a gradient approach to the teaching of mountaineering.

The gradient approach to teaching high risk activities has

proven successful at California State University, Northridge, where

it has been employed for the past fourteen years.

The concept behind

gradient education is that students be gradually exposed to new

material and that each installment is a logical outgrowth of

3

material already presented.

This approach to teaching is particularly

applicable to outdoor education because it appears to minimize the

stresses associated with high risk activities.

It is thus recommended that students learn all climbing fundamentals, including rappel and belay techniques, in the classroom

before venturing onto rock.

It is further recommended that the

initial climbing session emphasize mastery of fundamentals and

that practice be done on a boulder with minimal exposure (student•s

feet no more than six feet off the ground).

Follow-up climbing sessions should only gradually increase in

difficulty.

Students should practice both 5th class climbing and

rappel techniques on short routes (about 20 feet) before venturing

onto routes with increased exposure.

If the entire course is

conducted in this gradient manner, the instructor will find that

virtually all students are capable of overcoming their fears and

will successfully complete climbing problems of moderate difficulty.

TEACHING METHODOLOGY

The new instructor is invited to review the two books on

teaching methods recommended in the accompanying bibliography.

The

first, Freedom to Learn, discusses techniques for making instruction

more meaningful and significant to the student.

The second, To

Nurture Humaneness, discusses the role of humaneness in education.

This book would seem particularly appropriate for. a class in Basic

Mountaineering -- a class which by its very nature emphasizes close

jt······

4

personal contact between instructor and students.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A selected bibliography has been provided for the instructor.

In addition to the two books recommended above, the bi"bliography

includes reference works on mountaineering and related topics.

The

new instructor should pay particular attention to the references on

mountaineering first aid procedures.

5

COURSE OUTLINE

BASIC MOUNTAINEERING

WEEK #

LESSON

1.

Administrative Requirements (Classroom)

2.

Fundamentals of Climbing (Slides) & Equipment (Both in classroom)

3.

Climbing Techniques (Slides) &Basic Knots (Both in classroom)

4.

Proper Belay Techniques & Rappel Technique (Both in classroom)

5.

Climbing Fundamentals (Field)

6.

3rd and 4th Class Scrambling (Field)

7.

Beginning Rappeling (Field)

8.

Beginning 5th Class Climbing (Field)

9.

Chimney Climbing (Field)

10.

Intermediate Rappeling (Field)

11.

Intermediate 5th Class Climbing (Field)

12.

Field Evaluation Day (Field)

13.

Route Finding & Cross-Country Travel (Classroom)

14.

Review (Classroom)

15.

Written Final (Classroom)

TEXTBOOK:

Robbins, Royal.

Basic Rockcraft, La Siesta Press, $2.95

EVALUATION:

Field Evaluations:

50%

Written Fin a1:

50%

~

.

6

CLASS CLIMBING EQUIPMENT

Reference is made in the lesson plans to use of a complete set of

class climbing gear.

The following is the minimum amount of gear

required to teach a class of 25 students.

4 11mm climbing ropes, kernmantle, 150 ft.

5 Climbing helmets

25 Body slings, 111 webbing, 9 ft. lengths

25 Prussik loops, goldline, 4 ft. lengths

(also used for practice knot tying)

12 Carabiners, locking

24 Carabiners, non-locking

6

Runners, 1 11 webbing, 12 ft. lengths

6

Leaders, 111 webbing, 20 ft. 1engths

1 Expedition quality first-aid kit

7

LESSON PLANS

8

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

1

TIME REQUIRED:

1-2 hours

UNIT:

Administrative Requirements

TYPE OF UNIT:

Lecture

EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Activity Releases

Course Outlines

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should leave with a clear understanding of what will

be expected of them during the semester.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Hand out course outline and discuss with students.

Insure

that each student understands the course requirements.

2.

Briefly discuss safety considerations pertinent to the

climbing session.

Pass out activity releases and have

each student complete one.

3.

Take roll, add new students, etc.

9

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

2-A

TIME REQUIRED:

1

hour

UNIT:

Climbing Fundamentals

TYPE OF UNIT:

Lecture

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Slide Projector

Slide Set #1

Narrative #1

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be ab 1e to describe the fo 11 owing fundamenta 1s:

climbing classifications, belaying, proper use of legs, balance/

friction, slab climbing, three point rule, and basic hand and

foot holds.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

Note:

Instructor should familiarize himself with narrati.ve

before class so that presentation may be conducted without

reading.

The sequence of slides is exactly geared to narration.

Slide lecture is intended to last 30-35 minutes, thereby

leaving time for introduction beforehand, and question/answer

10

CLIMBING FUNDAMENTALS CONTINUED:

period afterwards.

SLIDE #

CONTENT

1

Introduction:

Climb with extreme exposure

2

Introduction:

Climb with minimal exposure

3

Classifications:

Class I

4

Classifications:

Class II

5

Classifications:

Class III

6

Classifications:

Class IV

7

Classifications:

Class V

8

Classifications:

Class VI

9

Belaying:

The Belayer

10

Belaying:

Leader placing protection

11

Belaying: Top-roped climb

12

Equipment:

A quick overview

13

Equipment:

All that is needed to get started

14

Proper Use of Legs:

Legs stronger than arms

15

Proper Use of Legs:

Resting on legs

16

Balance

Wrong

17

Balance

Correct

18

Balance -- Wrong

19

Balance -- Correct

20

Slab Climbing --Wrong

21

Slab Climbing -- Correct

22

Three Point Rule

11

CLIMBING FUNDAMENTALS CONTINUED:

SLIDE #

CONTENT

23

Three Point Rule -- Wrong

24

Three Point Rule -- Wrong

25

Three Point Rule -- Correct

26

Footholds:

Toeing

27

Footholds:

Edging

28

Footholds:

Sloping

29

Footholds:

Incorrect use of knees

30

Footholds:

Lifting foot instead of knee

31

Footholds:

Can stand on foot, not knee

32

Basic Handholds

33

Fingernail hold

34

Cling hold

35

11

36

Pinch hold

37

Downpressure hold

38

Anyone can climb ...

39

If he has a belayer

Thank God 11 hold

12

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

2-B

TIME REQUIRED:

1 hour

UNIT:

Equipment

TYPE OF UNIT:

Lecture

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Samples of shoes, boots, ropes, webbing, carabiners, and a

helmet.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to identify major items of climbing

gear, describe their characteristics, and know their function.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

I.

Shoes

A.

Any snug fitting tennis shoe, sneaker, or jogging

shoe is adequate

B.

Kletterschuhes:

soft rubber soles for improved friction

1.

Smooth soles:

2.

Lug soles:

intended for sandstone

intended for 11 gritty 11 or wet rock, also

superior for direct-aid climbing

13

EQUIPMENT CONTINUED:

C.

Climbing Boots:

heavier and narrower sole than hiking

boots

1.

Superior for climbing expeditions which imvolve

foot travel

2.

Superior for direct-aid

3,

Inadequate for narrow jam cracks

4.

Necessary for cold weather and high altitude climbing

"

II.

Clothing

A.

Proper clothing is function of weather conditions

B.

Long pants prevent cuts and scrapes (should be loose

fitttng)

III.

C.

Bare midriffs susceptible to rope burns-

D.

Scarves required to keep long hair safely tucked away

Climbing Ropes

A.

Natural fiber ropes (manila, sisal, etc.) are unsafe

B.

Nylon ropes are elastic and will better absorb forces

of a fa 11

C.

Kernmantle (llmm- Average 6,000 lb. strength)

1.

Core and sheath construction:

thousands of nylon

fibers run the length of the rope and are protected

by an outer sheath

2.

Favored for long climbs because smooth exteriors

generate less friction (when pulled through

carabiners, etc.)

14

EQUIPMENT CONTINUED:

3.

Superior coiling and handling characteristics

4.

Bright colors make them easier to tell apart when

more than one rope is utilized

D.

Goldline (7/16

1.

11

-

Average 5,000 lb. strength)

Twisted construction:

three main strands tightly

twisted around each other

2.

Major advantage is less expensive (approximately

1/2 price of kernmantle)

E.

Care of the climbing rope

1.

Inspect before and after each use

2.

Never step on a climbing rope

3.

Do not store a rope where it will be exposed to

sunlight

4.

Do not allow a rope to come in contact with

petroleum products

5.

Do not abuse the climbing rope

6.

Store the rope properly in a clean cool place out

of the sun, coiled loosely, and all knots removed

IV.

Nylon Webbing

A.

1 Tubular most common {approximately 4,000 lb. strength)

B.

Uses

11

1.

Swami belt:

a long piece tied around the waist

five or six times

2.

Runners:

9 to 20 foot lengths, used for anchors

15

EQUIPMENT CONTINUED:

3.

Body slings:

9 foot lengths used for tying

ndiapern harness

4.

Etriers:

short webbing ladders

C.

Water knot traditionally used to tie webbing

D.

Sewn webbing is stronger than tied:

knots reduce

strength, sewing (where done properly) does not

V.

Carabiners

A.

nsafety pinn - like devices used to clip elements of

the climbing chain together

B.

Aluminum carabiners rated to average of 3500 lb. strength

C.

Three general styles

1.

Oval:

least expensive and most popular, used for

most climbing purposes, superior for carabiner brake

rappels

2.

non:

stronger than ovals, used on hard leader climbs

3.

Locking:

special purpose carabiner used whenever

greater security is desired, most expensive

VI.

Helmets

A.

Protects falling climber, also protects from falling rock

B.

Must have suspension system which keeps hard outer shell

off of wearer's head

C.

nyn strap design superior to single chin strap

D.

Straps should be of non-stretchable nylon; elastic

straps poor

16

EQUIPMENT CONTINUED:

E.

Buckles or 11 011 ring fasteners superior to snaps (which

can come unsnapped)

V1I.

Found Equipment:

Climbing gear found abandoned must never

be used

A.

Nylon deteriorates in sunlight and heat

B.

Metal objects subject to impact stress hardening if

dropped

17

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

3-A

TIME REQUIRED:

1 hour

UNIT:

Climbing Techniques

TYPE OF UNIT:

Lecture

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Slide Projector

Slide Set #2

Narrative #2

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to describe the following techniques:

mantleshelving, counterforce, crack jamming, chimney stemming,

and rappeling.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

Note:

Instructor should familiarize himself with narrative

before class so that presentation may be conducted without

reading.

narration.

The sequence of slides is exactly geared to the

Slide lecture is intended to last 30-35 minutes,

thereby leaving time for introduction and question/answer period.

18

CLIMBING TECHNIQUES CONTINUED:

SLIDE #

CONTENT

1

Introduction

2-11

Mantleshelving

12-13

Counterforce

14

Layback

15-22

Crack jamming

23-30

Chimney technique:

31-33

Downclimbing

34-42

Rappe ling

squeeze and stemming

19

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

3-B

TIME REQUIRED:

1 hour

UNIT:

Knots

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Practical Exercise

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

All climbing ropes

All prussik loops

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A (No climbing involved)

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to tie the five basic climbing knots

which wi 11 be used in the class:

bowline-on-a-coil, figure of

eight, double fisherman's, prussik, bowline.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Distribute the goldline prussik loops, one to each class

member.

Lay out the climbing ropes such that each end is

free for knot tying.

2.

Demonstrate the tying of each knot.

Proceed in a slow

manner, such that students can follow with their individual

ropes.

Explain the use of each knot:

20

KNOTS CONTINUED:

Bowline-on-a-coil:

For climber tie-in

Figure of Eight:

Places loop in rope for person or

for tie-in, also used in establishing rappel anchor

Double Fisherman's: Ties two ropes together

Prussik:

Used for self-belay

Bowline:

Places loop in rope, commonly

used for anchoring rope to tree

or boulder.

3.

Repeat each knot until class thoroughly familiar.

Supervise

closely to insure everyone is tying knots correctly.

21

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

4-A

TIME REQUIRED:

1 hour

UNIT:

Belay Technique

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Practical Exercise

EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Complete class set of climbing equipment

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A (No climbing involved)

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate the correct procedure for

setting up and conducting a belay.

They should further be able

to demonstrate a complete knowledge of belaying terminology.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select an outside area near classroom. Area should have

trees, bike racks, or related features suitable to serve

as anchor points.

2.

Uncoil and lay out the four climbing ropes.

Loop a separate

piece of webbing around anchor for each rope, and clip in

with a locking carabiner (much in the same manner as

establishing a top-roped belay).

3.

Direct a student to tie into one end of each rope, utilizing

22

BELAY TECHNIQUE CONTINUED:

the bowline-on-a-coil knot.

4.

Demonstrate proper belaying technique, emphasizing that the

belayer must never remove the braking hand from the rope

(not even momentarily).

5~

Discuss the role of correct belaying terminology:

Climber:

6.

Be layer:

11

0n belayr

11

Belay on 11

11

Climbing 11

11

Cl imb 11

11

Slack 11

Give slack

11

Up rope 11

Take in rope

11

0ff belay 11

11

Belay Off 11

Allow each student opportunity to practice role of both

climber and belayer, in both up and downclimbing situations.

Supervise closely for safe procedure and correct use of

tenninology.

23

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

4-B

TIME REQUIRED:

1 hour

UNIT:

Rappel Technique

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Practical Exercise

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Complete set of class equipment

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A (No climbing involved)

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Each student should be able to demonstrate correct procedure for

arranging the Yosemite carabiner brake rappel system.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Use same outside area employed in lesson 4-A (Belay

Technique).

2.

Using same anchors, attach the middle of each doubled rope

to the anchoring carabiner (locking) with a figure of eight

knot.

3.

Explain procedure to class.

Demonstrate the tying of a diaper seat harness.

Have class

follow with their own body slings.

4.

Demonstrate Yosemite carabiner brake rappel system,

explaining its advantages over other systems (reliable,

24

RAPPEL TECHNIQUE CONTINUED:

safe, no extra gear required).

5.

Demonstrate self-belay with a prussik knot.

6.

Demonstrate a simulated rappel, emphasizing correct feet

and body position and proper use of braking arm.

7.

Allow each class member to practice a simulated rappel.

Supervise closely for correct procedure.

25

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

5

TIME REQUIRED:

2 hours

UNIT:

Fundamentals of Climbing

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

None

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

All climbing to be done close to the ground (student•s feet

never more than six feet off the ground), therefore, no belay

is required.

Class must be trained in spotting techniques and

a minimum of two spotters provided for each student actually

climbing.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate mastery of the following

climbing fundamentals:

proper use of hands and feet, proper

balance, and knowledge of three point rule.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select a practice boulder with an absolute minimum of

exposure.

At least one side should have a gently sloping

face for practice of friction and balance techniques.

26

FUNDAMENTALS OF CLIMBING CONTINUED:

2.

Instructor demonstrates and thoroughly explains all climbing

fundamentals:

proper balance, toeing vs. edging, necessity

of taking short moves, three point rule, and basic handholds.

3.

Allow each student opportunity to practice fundamental

techniques to the point of total familiarity.

students to spot each other.

Train

Closely supervise to insure

that each climber has a minimum of two spotters.

27

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

6

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

3rd & 4th Class Scrambling

TYPE OF UNIT:

Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Helmets; llmm rope

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

Climbers and belayers both must wear helmets.

All climbers,

even on 3rd class, must be belayed.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate the ability to apply

climbing fundamentals to actual climbing situations.

Additionally, each participant should learn how to set up and

conduct a belay using no gear other than the climbing rope.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select a moderately long (50-60 feet) 3rd or 4th class route.

2.

Demonstrate the method of setting up a belay using rope only.

Required knots:

bowline (for anchor), figure eight (for

belayer tie-in), and bowline-on-a-coil (for climber tie-in).

3.

Allow each student opportunity to both climb the route and

to belay another student (under close supervision).

28

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

7

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Beginning Rappel

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Complete set of class equipment

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

All rappelers must wear helmets and be on belay.

Instructor

must supervise closely to insure that every individual has

correct hook-up before descending.

Instructor must closely

supervise each stage of the descent -- watching for correct

balance, placement of feet, and overall safety consciousness.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate proper rappel technique,

including:

anchoring, harness and carabiner arrangement, body

position, and belay.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select beginning rappel site.

Criteria for selection:

about 20-30 feet rappeling distance (free of overhangs or

other obstructions), safe and easy access to top, and

absolutely secure anchor.

29

BEGINNING RAPPEL CONTINUED:

2.

Demonstrate Yosemite carabiner rappel hook-up.

3.

Demonstrate rappel, emphasizing the following points:

correct body position and foot placement, correct use of

brake hand, proper dialogue with belayer.

4.

Allow each class member opportunity to rappel at least

once.

above.

Supervise closely for safety considerations outlined

30

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

8

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Beginning 5th Class Climb

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Helmets, climbing rope, sufficient webbing and carabiners to

establish top-roped belay.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

Top-roped belay required (bowline-on-a-coil tie-in), helmets

required for both belayer and climbers.

instructor or trusted assistant.

Belayer should be

Close supervision required

throughout.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to apply climbing fundamentals to easy

5th class climbing situation.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select easy 5th class climb (about 5.1-5.3).

selection:

Criteria for

short length (about 20-30 feet), all or part of

climb should involve crack of 3-4 inch width, easy and safe

downclimb available, absolutely secure anchor for top-roped

belay.

31

BEGINNING 5th CLASS CLIMB CONTINUED:

2.

Establish top-roped belay, explaining procedure to class.

3.

Demonstrate the correct hand, fist, and foot jams required

to ascend the crack portion of the route.

Emphasize

necessity for short moves.

4.

Allow each class member opportunity to climb.

Supervise

closely for correct hand and foot placements, balance,

three point rule, etc.

32

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

9

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Chimney Climbing

TYPE OF UNIT:

Demonstration - Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Helmets, climbing rope, sufficient webbing and carabiners to

set up belay anchor.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

Top belay required.

Climber and belayer must wear helmets.

Close supervision demanded throughout.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate the fundamentals of

chimney technique.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select chimney climbing route.

Criteria for selection:

moderate length (about 15-20 feet), adequate width for

stemming (about 3 feet), easy and safe downclimbing route,

adequate site for top belay, absolutely secure belay anchor.

2.

Establish top belay position, explaining procedure to class.

3.

Demonstrate and explain the alternate hand and foot placements of correct stemming technique.

33

CHIMNEY CLIMBING CONTINUED:

4.

Allow each class member opportunity to climb chimney at

least once.

Closely supervise for correct procedure and

adherence to safety consciousness.

34

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

10

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Intermediate Rappel

TYPE OF UNIT:

Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Complete class set of climbing equipment.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

All rappelers must wear helmets and be on belay.

Instructor

must supervise closely to insure that every individual has

correct hook-up before descending.

Instructor must closely

supervise each stage of the descent watching for correct

procedure throughout.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate proper rappel technique,

including:

anchoring, harness and carabiner arrangement,

correct body position, and belay.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select the intermediate rappel site.

Criteria for selection:

moderate length (about 50-60 feet), free of overhangs or

other hazards, safe and easy access to top, absolutely

secure anchor.

35

INTERMEDIATE RAPPEL CONTINUED:

2.

Set up belay and rappel, explaining each step to the class.

3.

Demonstrate Yosemite carabiner-brake rappel hook-up.

4.

Demonstrate rappel, emphasizing the following points:

correct body position and foot placement, correct use of

brake hand, proper dialogue with belayer, and proper

procedure throughout.

5.

Allow each class member opportunity to rappel at least

once.

Closely supervise for safety considerations

outlined above.

36

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

11

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Intermediate 5th Class Climb

TYPE OF UNIT:

Field Experience

EQUIPMENT &SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Helmets, climbing rope, sufficient webbing and carabiners to

establish top-roped belay.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

Top-roped belay required (bowline-on-a-coil tie-in), helmets

required for both belayer and climbers.

instructor or trusted assistant.

Belayer should be

Close supervision required

throughout.

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to apply climbing fundamentals to a

moderate 5th class climbing situation.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

1.

Select moderate 5th class route (about 5.5-5.6).

for selection:

Criteria

moderate length (50-60 feet), easy and safe

downclimb available, absolutely secure anchor required for

top-roped belay.

37

INTERMEDIATE 5th CLASS CLIMB CONTINUED:

2.

Establish top-roped belay, explaining procedure to class.

3.

Allow each class member opportunity to climb.

Supervise

closely for correct procedures throughout and adherence

to safety considerations.

38

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

12

TIME REQUIRED:

2+ hours

UNIT:

Field Evaluation Day

TYPE OF UNIT:

Field Experience

EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

Complete set of class equipment, minus helmets.

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A (No actual climbing involved)

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate all the field techniques

experienced in the class.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

Class participants will be evaluated on their abilities to

perform five or more of the following tasks (randomly selected).

Criteria for evaluation:

1.

degree of mastery of each technique.

Tie one or more of the following knots:

figure eight,

bowline, bowline-on-a-coil, prussik, or double fisherman's

knot.

2.

Coil a climbing rope.

3.

Demonstrate and explain toeing vs. edging.

4.

Demonstrate and explain proper balance.

39

FIELD EVALUATION DAY CONTINUED:

5.

Demonstrate and explain the three point rule.

6.

Demonstrate and explain counterforce.

7.

Demonstrate and explain one or more of the following jams:

hand, thumb, finger, fist, foot, or toe.

8.

Demonstrate and explain one or more of the following

handholds:

pinch, cling,

11

thank god 11 , downpressure.

9.

Demonstrate and explain the setting up of a belay anchor.

10.

Demonstrate and explain the setting up of a rappel anchor.

11.

Demonstrate and explain the diaper harness.

12.

Demonstrate and explain the Yosemite carabiner brake rappel

system.

~

'

40

DAILY LESSON PLAN

CLASS:

WEEK:

Basic Mountaineering

13

TIME REQUIRED:

2 hours

UNIT:

Cross-Country Travel & Routefinding

TYPE OF UNIT:

Lecture

EQUIPMENT & SUPPLIES REQUIRED:

None

SAFETY CONSIDERATIONS:

N/A

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES:

Students should be able to demonstrate knowledge of how to apply

the principles of Basic Mountaineering to cross-country travel

situations.

OUTLINE OF CONTENTS:

I.

Routefinding:

A.

Sources of Information

Topographic Maps:

Briefly describe the map and its

contents, giving directions on where to go for map

training.

B.

Guide Books:

Briefly revie\'1 the Sierra Club Climbing

Classification System used in most guides.

C.

Rangers, guides, and other professionals.

41

CROSS-COUNTRY TRAVEL & ROUTEFINDING CONTINUED:

II.

Mountain Terminology Applicable to Routefinding and

Cross-Country Travel

A.

Col:

saddle

B.

Ridge:

C.

Couloir:

deeply shaded gullies filled with ice or snow

D.

Cirque:

head of a mountain valley, rounded like end of

spur or arm

a football stadium

E.

Talus:

sloping rockfall composed of boulders and other

large fragments

F.

Scree:

sloping rockfall composed of the smallest

fragments

G.

Moraines:

piles of sand and rock at the terminus of a

glacier, or debris left behind by a receding glacier

III.

General Principles of Routefinding

A.

Ridges:

freedom from rockfall and avalanches, but

exposed to weather

B.

Couloirs:

dangerous during daylight hours as debris

melts loose and slides down

C.

Moraines:

insecure, precarious equilibrium, should be

avoided

D.

11

Climb with the eyes 11 :

look far ahead, planning routes.

Look for ridges with lower than average inclination,

cracks, ledges, chimneys or related routes.

E.

Tilted slabs best climbed from the upslab side

42

CROSS-COUNTRY TRAVEL & ROUTEFINDING CONTINUED:

IV.

Cross-Country Travel

A.

Brush

1.

Avoid if possible, even if route is significantly

lengthened

2.

Stay high, sticking to ridges as possible

3.

Seek game trails

4.

May be possible to proceed up stream channel to

avoid brush

B.

Talus and Scree

1.

Proceed steadily:

momentum is the best defense

against a teetering rock

2.

Avoid the fall line of climbers above and below

3.

If possible, avoid volcanic talus and scree:

rapid disintegration leaves even huge boulders

delicately balanced

C.

Streams

1.

Cross at widest point

2.

Unfasten waist band of pack

3.

Wear foot protection -- tennis shoes preferable

to boots

4.

Loose clothing increases drag from rapidly moving

water

5.

If water is not clear, probe ahead with a pole

6.

Face upstream on crossing

43

CROSS-COUNTRY TRAVEL & ROUTEFINDING CONTINUED:

7.

If water boils above the knee, it is dangerous

a.

Leader must be belayed

b.

Belay should be placed as far above crossing as

possible

c.

Personnel should stand by bank at point where

belay pendulum would end (they serve as

rescuers should the leader need assistance)

d.

Leader establishes handline for security of

rest of party

e.

Last member belayed from far shore

44

SLIDE NARRATIVES

45

NARRATIVE

SLIDE SET I

INTRODUCTION

Basic Mountaineering is a sport of seemingly endless variety.

Depending on the climber's interests and the rock available, the

sport can be practiced barely inches off the ground or from heights

so dizzying that even the birds are careful.

Some good climbers

practice rock gymnastics which require no special gear -- not even

footwear.

Others wouldn't dream of heading to the rock without

hundreds of dollars worth of gear.

Some people climb for a little

exercise and outdoor fun, nothing more.

Others pursue risk,

adventure, and a chance to test their limits.

The style of climbing

you choose is wholly determined by your own desires and inclinations.

CLIMBING CLASSIFICATIONS

Because climbing does exist in such variety, classification

systems have been devised to describe the difficulty of any climb.

The most common classification system was developed by the Sierra

Club.

Under the Sierra Club system, climbs are divided into six

separate classes:

CLASS I:

Walking upright; no special gear required.

CLASS II:

Scrambling over rocks; special footgear required.

Hands needed for balance.

46

CLASS III:

Scrambling over steeper rocks.

techniques required.

Proper climbing

Rope should be available, but

not usually required.

CLASS IV:

Situations where the climber is exposed to the danger

of a severe fall.

CLASS V:

Rope is necessary.

Difficult climbing up nearly vertical rock faces.

Rope and technical climbing gear required.

CLASS VI:

Climbing on rock where foot and hand holds are

inadequate to support the climber.

Direct aid in

the form of stirrups and related gear is required.

BELAYING

Belaying is a climbing term which has nautical origins.

On

sailing vessels, wooden pins (belays) were provided for lowering

canvas sails.

The friction produced by wrapping a rope around the

belay pin made it possible to lower heavy sails by hand.

ln a

similar manner, a person holding a climbing rope {_the belayer) can

use friction to stop the downward plunge of a falling climber.

In practice situations, the climber is protected by a top roped

belay, that is, the belay rope is anchored above the climber.

In

most mountaineering situations, however, it is not possible to toprope the climber.

In these situations, the climber utilizes either

pitons, chocks, or bolts to create his own anchor points as he climbs.

The belay rope is essential to safe climbing.

Under no circum-

s.tances should anyone venture more than five or six feet off the

ground without the security of a rope and belayer -- and this is

47

regardless of whether the climb is top-roped or the lead climber is

placing his own protection.

EQUIPMENT

Mountaineering gear comes in a confusing variety of ropes,

slings, pitons, carabiners, and related equipment.

Technical

expertise is required for the safe use of such equipment.

The

beginner, however, can get started with little more than a pair of

old 11 tennies 11 •

Snug fitting shoes are all that is needed to practice

beginning techniques close to the ground.

Proper clothing depends on the weather.

Obviously different

clothing is required for a Himalyan ascent than is seen on sunny

California boulders.

In general, though, clothing should be

comfortably loose, but not baggy.

Denims are superior to shorts

because of the protection provided against scrapes and scratches.

When the beginner is ready to venture more than a few feet

off the ground, safety demands the addition of two items of

equipment:

the belay rope and a helmet.

PROPER USE OF LEGS

The first rule to learn is that climbing is done almost totally

with the legs.

Old-timers like to emphasize this principle by

referring to that animal which is perhaps the best climber of all

of nature's realm--the mountain goat.

Obviously, the mountain goat

makes little use of hands and arms for scrambling up and down the

treacherous slopes of his rocky domain.

Yet, despite the obviousness

48

of this principle, an embarrassingly large number of beginners harbor

the misconception that rock climbers are muscle-bound gymnasts who

pull themselves upwards by the sheer power of bulging biceps.

And

because of this misconception, many potential climbers shy away from

their first mountaineering experience on the grounds that they are

11

not strong enough 11 •

This is an unfortunate misunderstanding.

In

reality, anyone having the strength to climb stairs has the strength

to be a rock climber.

The reason for the importance of one's legs while climbing is

actually quite simple.

The muscles of the leg, particularly the

hamstrings and quadriceps of the thigh, are much larger and correspondingly stronger than their equivalents in the arm.

It is possible

to lift oneself with the legs (as in climbing stairs) almost indefinitely if a moderate pace is set.

In contrast, not too many climbers

are likely to be capable of more than a dozen or so pull-ups.

Even

the most diehard and gnarled mountaineer cannot do many pull-ups as

compared to the number of stairs a rank amateur can ascend.

then, are the most important climbing appendages.

The legs

If you have trouble

remembering, then keep in mind our woolly champion, the mountain goat.

BALANCE AND FRICTION

Two of the most important climbing fundamentals, proper balance

and good friction, are best treated together since it takes the right

balance to get the best friction.

The importance of one's legs in

climbing has already been discussed.

Since most of the body's mass

is moved by the legs, it stands to reason that most of one's weight

49

will be supported by the feet.

Thus the key to climbing, or at least

the key to not falling, is to keep one's feet firmly in contact with

the rock.

Foot placement would be of no concern if rocks came

equipped with perfectly level ledges and footholds.

such is not the case.

But, of course,

Footholds will frequently be slanted slabs,

dished-out areas, or rounded protuberances.

The friction of rubber

soles adhering to the rock surface is the element which keeps the

climber from slipping off these less-than-perfect holds.

Friction

is thus the essence of climbing and correct balance is the essence

of friction.

The more weight a climber has pushing his soles into the rock,

the better will be the resultant friction.

Correct balance involves

keeping the body as nearly vertical as possible.

In this manner, the

climber's entire weight will be directly over his feet, and gravity

works in the climber's favor by pressing his feet to the rock.

The

problem is that beginners tend to like the false sense of security

derived from leaning in towards ( 11 hugging 11 ) the rock.

Instead of

providing real security, leaning in can make climbing precarious.

If your weight is not directly over your feet, gravity works

against you.

The body will have a tendency to pivot on its center

of gravity--as the head and torso are pressed to the rock, the feet

will be pushed in the opposite direction (away from the rock).

Need

more be said?

As is true of most important concepts, there is more to balance

than might first be suspected.

In addition to maximizing friction,

50

proper balance has two additional benefits.

If the body is kept

vertical, much of one•s weight will be supported by bone structure.

And the more weight that is supported by bone, the less there is to

be held by muscle power alone.

Thus, correct balance greatly reduces

muscle fatigue and goes a long way towards preventing what is known

in climber•s jargon as

11

sewing machine leg 11 (exhausted and trembly

legs).

One final advantage of correct balance needs to be mentioned.

A stable and vertical body position is the ideal base from which to

make subsequent moves.

If a climber is leaning close to the rock,

his vision will be reduced to the point he may not be able to look

ahead for his next holds.

And an awkward, unstable position might

easily be lost in the process of reaching for that next hold.

Balance, in all its aspects, is as important to proper climbing as

is good friction, and these are the skills which should be learned

first.

SLAB

CLif~BING

The term 11 Slab 11 refers to sloping rock which lies at an angle

of about 45 degrees.

If the rock lies at a much lower angle, no

technique is required to walk across it.

And if the slab lies at a

much steeper angle, then it becomes a face and is climbed with the

aid of hand and footholds.

It is only that midrange of about 45

degrees where neither face climbing techniques nor simple walking

are effective, that the climber enters the realm of a new category of

techniques:

slab climbing.

51

More likely than not, slabs will not offer usable hand or footholds, they must be climbed relying primarily on friction.

This

discussion of slab climbing will thus be closely related to the

previous discussion of friction and balance.

The traditional method

for climbing slabs is for the climber to lean forward and press his

palms flat to the rock, while maintaining his weight predominantly

over his feet (bending at the ankle helps}.

But only orangutans

and their close cousins have the flexibility to keep both hands and

feet flat on steep slabs.

The climber must compromise somewhere--

usually by leaning forward too far and not keeping his weight

properly over his feet.

A superior method is to climb slabs in a switchback fashion

rather than making a bee-line for the top.

Only by so doing can the

climber get consistently good foot placement.

Remember, the key to

proper friction is to keep the foot flat on the rock and to keep the

body•s weight directly over the feet.

If the toe is straight uphill,

the climber will unconsciously lift his heel as he leans forward to

place palms against the rock.

Lifting the heel removes about half

the sole from the rock and thus cuts friction in half.

At the other

extreme, if the foot is placed sideways on the rock (perpendicular

to the slope}, then the foot will roll to the downhill side--this too

greatly reduces friction.

The ideal foot placement is halfway

between these two extremes; that is, the toes should point off at

about 45 degrees to the side of straight uphill.

The easiest way

to keep the toes pointed in the proper direction is simply to climb

52

in that direction.

Thus it is easier to zigzag or switchback up a

slope than to head straight for the top.

The hand nearest the slope

is held against the rock to help maintain proper balance.

If any

cling holds are available, then the hands can be put to greater use.

The essence of good slab climbing is "style".

In other words,

good footwork, balance, and methodic movement are more important than

strength or brute exertion.

The climber should at all times keep a

keen eye for cups or other small undulations which will provide

optimum foot placement.

Large steps should not be taken and all

movements must be deliberate and methodical.

The purpose of moving

cautiously is to minimize the chances of any action having the

unexpected reaction of sending oneself sliding winsomely down the

slab.

Remember, friction alone holds the climber to a steep slab.

Once he breaks loose, the next stop is ground level.

Unless, of

course, the climber is roped--and roped he must be on any slab more

than about 10 feet in height.

THREE POINT RULE

Whenever a climber is about to make a move, he should ideally

be in a stable and balanced position in which both hands and both

feet are secure.

No great risk is thus encountered by moving one

hand or one foot--three points of contact still remain.

is the three point rule:

This then

try to never move more than one appendage

at a time and keep three points of contact with the rock whenever

possible.

But a surprisingly large number of climbers, beginners

and advanced alike, frequently violate this rule.

For them, ths

53

urge is sometimes strong to move both a hand and a foot at the same

time.

This urge must be resisted.

If you are in the habit of leaving yourself with only two points

of contact, sooner or later a foot or hand is going to slip.

The

sole remaining point of contact will not be enough to hold your

weight and a fall could easily result.

fall would most likely not be injurious.

risk?

If properly belayed, such a

But why take a needless

Remember the three point rule, and move only one foot or one

hand at a time, not both together.

FOOTHOLDS

As the legs are more important than the arms in climbing, the

finding of good footholds is a matter of prime concern.

New climbers

typically have hopes and expectations for broad or level footholds.

But if the principles of balance and friction are kept in mind, then

some mighty tiny looking holds will be found to be perfectly serviceable (assuming, of course, that anything can be kept in mind while

groping up the face of a cliff).

Should a potential foothold look

at all suspect, it must be tested before one's entire weight is

entrusted to it.

When a foothold is level and spacious, no special skill is

required.

But if the hold appears otherwise, then the following

techniques should prove of value:

TOEING vs. EDGING:

Holds of very small width are best

approached with the side of the foot, not the toes.

If the toes

alone are making contact, then the foot must be held level by muscle

54

power.

This places strain on the calves and 11 sewing machine leg 11 can

result.

In contrast, if the edge of the foot is placed on the hold,

leg muscles can relax and let the bones do most of the work.

Which

side of the foot is edged onto a hold will depend largely on the

direction the climber is moving.

The important point to remember is

that either edge of the foot is generally superior to toes alone.

SLOPING FOOTHOLDS:

These will be encountered either as shallow

depressions in vertical rock or in the form of uneven ledges of

varying size.

The intent is to get as much of the boot on the sloping

surface consistent with maintaining proper balance.

This can be done

by planting the foot with the toe facing uphill and by bending at the

ankle to keep the leg vertical.

KNEES:

When the next good foothold is almost waist high, it

can be very tempting to use the knee rather than putting out the

extra effort to bring up a foot.

made.

But that extra effort must be

Knees are finicky creatures and they are readily subject to

injury.

A good way to injure the knee is to place it on a rough

rocky hold and then place the body•s entire weight on it.

Thus,

the foot must be brought up if at all possible.

Doing so will place

one is a better position to continue climbing.

If a foot has reached

the hold, one can easily stand on it.

But if the knee has been used,

the climber might find himself stuck and unable to rise to his feet.

HANDHOLDS

The importance of good footholds has been emphasized, but this

does not mean that handholds are to be taken lightly.

The value of

55

the security afforded by a good handhold cannot be underrated.

searching for handholds try not to overextend yourself.

should ideally remain at or below eye level.

When

The hands

The problems involved

in reaching high for that 11 Special 11 handhold are two-fold.

The

higher you reach, the more your body will be drawn into the rock-and this adversely effects balance.

Further, reaching high overhead

leads to the temptation to rely on the arms in 11 muscling 11 up the

rock, which, of course, can quickly lead to fatigue.

In most

situations, therefore, it is best to make short moves and use

intermediate holds as much as possible.

The types of holds encountered and the methods of using them are

as follows:

CLING HOLD:

The classic handhold is a protuberance of rock

which can be grasped firmly by the hand.

As the name implies, the

climber merely 11 Clings 11 to this type of hold.

Cling holds come in

an endless variety of shapes and sizes, and they are the most

commonly sought hold.

FINGERNAIL HOLD:

If cling holds are encountered which are too

small to be grasped securely, they can still be used as

holds.

11

11

fingernail 11

The fingers are curled down and the tips of the fingers (or

fingernails 11 ) are brought down upon the hold.

If properly executed,

the fingernail cling can allow the climber to effectively utilize

some surprisingly minuscule holds.

THANK GOD HOLD:

A cling hold which slopes downward and inward

affords the climber with the best of all possible grips.

If such a

56

hold is encountered near the end of a hard climb or at any other time

when the climber is becoming fatigued, then the name for the hold is

self-explanatory.

A student once reflected that a particular 11 Thank God 11 hold felt

so good she was tempted to move in with bed and board.

Such a feeling

of security is quite natural; however, it can lead to trouble.

The

climber should not rest unless his/her feet are on secure footholds.

When resting, the climber's weight must be supported by bone

structure, not muscle.

If a rest pause is taken at a 11 Thank God 11

hold, the natural tendency is to have the arms supporting too much

weight.

Fatigue can set in, and the climber can find himself in

trouble.

11

Thank God 11 holds can in fact be godsends, but they must

not be relied upon excessively.

PINCH HOLDS:

The pinch hold is a specialized form of grip

utilized on protuberances which are overhanging, or otherwise

positioned in an awkward manner that does not allow them to be

gripped as cling or fingernail holds.

The climber simply

pinche~

the hold, and by so doing gains a bit of security.

DOWNPRESSURE:

S.loping ledges, dished out areas, and a few other

formations which might not otherwise provide handholds can be utilized

by pressing down upon them.

The heel of the hand is placed on th.e

hold and the climber pushes himself up somewhat in the manner of

doing a one-arm pushup.

Great strength is not required because the

climber most likely will be pushing himself up with his feet at the

same time.

57

NARRATIVE

SLIDE SET II

MANTLESHELVING

Mantles are flat ledges or shelves, as is found on many fireplaces.

They are usually encountered as the last move over the top

of a climb.

But they can also occur intermediately, as when a ledge

is come upon part way up a climb.

The technique known as mantle-

shelving is the most commonly utilized means of putting oneself up

and over these ledges.

Mantleshelving can be anything from very

easy to extremely difficult depending upon the peculiarities of the

mantle involved.

The easiest to master is the classic mantle--a

flat ledge at about chest height.

Flat mantles over one's head are

more difficult, but are still reasonable for the beginner.

Only when

the mantle is sloping or overhanging, or the ledge quite narrow, does

mantling move into the realm of the expert climber.

The classic mantle is accomplished with the hands placed about

a foot apart, palms flat on the ledge, fingers pointing towards each

other.

Push off with the feet and simultaneously lift up with the

arms and shoulder muse l es (in the manner of doing a pushup) .

Do not

attempt to muscle up with arms alone--especially if the mantle is the

last move of a tiring climb.

In one fluid motion, raise the body

until the arms are fully extended and the elbows lock.

This position

can be maintained as the locked bones of the arms will do most of the

58

supporting work and the arm muscles can relax somewhat.

Now lean

forward and slightly to one side and bring the opposite foot to the

ledge (no knees, please).

Try to place the foot flat and as close

to the body as possible.

With the help of a gentle pushoff from the

fingertips, straighten the leg and stand up.

is to doing the classic mantle.

And that is all there

The essence of the technique is in

smoothness and continuity of motion.

Great arm strength is not

required as the initial upwards thrust is provided by both arms and

legs lifting in unison.

Flat mantles higher than the climber's head can be gained in a

manner similar to the technique just described.

The only difference

is that proper use of the feet is increasingly important, and a

smooth continuous action is essential for success.

Grasp the mantle

with both hands and walk the feet up until the ledge is about chest

high.

Then quickly and smoothly shift the hands to the palm down

position, thrust off with the feet, and lift yourself up as in doing

a classic mantle.

COUNTERFORCE AND LAYBACKS

When pronounced hand and footholds are lacking, the climber is

frequently able to make use of a combination of opposed forces.

An

example of this principle has already been seen in the "pinch" handhold.

The opposing forces of the thumb pushing in the direction

opposite to the fingers provides the inward force which gives the

climber security.

climber.

Opposing outward pressures can also aid the

For example, if a crack is too wide to be sucessfully

p '

59

jammed with hand or fist, the climber can grasp the crack•s edges and

pull against the rock in opposite directions.

These counterforce

techniques are strenuous, but they can be effective if used sparingly.

One of the most useful variations of counterforce is the undercling hold.

The climber grips the bottom of a flake or undercut ledge

and attempts to

11

PU11

11

himself towards the flake.

At the same time,

he leans out from the rock by pushing .. with his feet.

11

The counter-

force provided by this opposing pushing and pulling holds the climber

in a secure position and gives him the opportunity to reach for his

next hand or foothold.

The classic form of counterforce is known as laybacking.

This

involves a combination of pushing and pulling forces similar to the

undercling hold, but the climber is actually able to ascend by using

a continuous combination of these opposed forces.

done in three basic situations:

Laybacking can be

at a corner where two rock faces

meet (if there is a crack between them), along any crack which has

one side offset sufficiently to allow room for the climber•s feet;

and finally, up a vertical flake.

Laybacking is the most strenuous form of counterforce, and the

beginner will have difficulty ascending more than a few feet.

The

hands grip the close edge of the flake or crack and pull the body in

while the legs push out.

hands.

The leading foot is kept just below the

If higher, the strain on the arms becomes too great.

lower, the feet will not maintain a good grip on the rock.

If

One foot

or hand is slid upwards at a time, and in this manner the climber

60

shuffles his way up the rock.

The arms are kept extended as much as

possible in order to transfer strain from muscle to bone.

But there

are limits to the amount of strain even the bones can hold, and the

beginner would be wise to limit his laybacking to short cracks and

flakes.

CRACK JAMMING

The stresses of expansion and contraction build up in rock until

the strain is relieved by the rock's splitting.

fissures are useful to climbers.

Most of the resulting

Horizontal cracks can be of assis-

tance by providing opportunity for conventional hand and footholds.

But of particular value are vertical cracks--these frequently provide

the only route up an otherwise smooth face.

Vertical cracks up to

about a foot in width are climbed by jamming a portion of the body

into them.

chimneys.

Wider cracks which admit the entire body are known as

The techniques of chimney climbing are distinct from

crack jamming, and thus will be considered separately.

Fingers, hands, fists, arms and shoulders; also toes, feet,

legs, and even knees have all been utilized in one or another form

of jam.

fits.

The idea is to shove into the crack whichever of the above

The selected body member is then flexed or twisted into a

position in which pressure is applied outwards to both sides of the

crack.

Sufficient pressure must be exerted to allow the "jam" to

hold the body's weight either partially or in full.

The climber is

then able to move upwards by repeating a sequence of jams.

easiest jams to accomplish involve the hands and feet.

The

The others

61

are awkward and strenuous and can require considerable determination

to master.

The ideal vertical crack for climbing is about 2 to 4 inches in

width.

Most new climbers can scoot up these with unexpected agility

because cracks of this width accept the easy hand and foot jams.

The

climber begins by jamming both hands and both feet into the crack,

and then he ascends by moving up one hand or one foot at a time.

These ideal cracks will vary somewhat in size, and climbers have

their individualities too (both in build as well as temperament).

Thus, use may be made of either the hand or fist jam, and similarly

either the toe or foot jam.

The proper application of each jam is

outlined below:

HAND JAM:

A hand is inserted into the crack, and then expansion

is obtained by tucking the thumb underneath the palm.

A variation

involves creating expansion with the fingers instead of just the

thumb.

The fingers are pressed hard against one side of the crack

in such a manner that the knuckles press tightly against the other

side.

The expansion created by both variations of the hand jam

create the outwards pressure needed to hold the hand securely in

place.

FIST JAM:

A hand is inserted into the crack, and then the

fingers are curled into a fist.

The expansion thus obtained can

provide good security, particularly if the fist is janmed into a

"bottleneck".

In other words, the fist should be jammed in a wide

portion of the crack and pulled back or down into a narrower portton.

62

To remove the fist jam, simply uncurl the fingers and the hand will

slide easily back and out.

TOE JAM:

The knee is lowered to the outside in order to allow

the tip of the foot (or toes) to be inserted sideways into the crack.

Then the knee is raised up, all the way up, until it is flush with

the crack.

This motion of raising the knee twists the toes tightly

into the crack.

The resulting jam is extremely secure and will

support one's entire weight.

stand very long on a toe jam.

But it is a rare climber who wants to

They can be quite painful, especially

if one is wearing tennis or jogging shoes.

In order to remove the toes, the knee has to be again dropped

to the outside.

Keep in mind that removal can be difficult if one

is in the habit of taking large steps.

Thus the key to proper crack

climbing is to proceed steadily, but gradually, taking steps of about

8 to 12 inches.

FOOT JAM:

the toe jam.

The foot jam is accomplished in a manner identical to

It is used in wider cracks which will accept the better

part of the climber's foot, not just his toes.

Climbing becomes more difficult when cracks are too narrow to

accept either hands or feet.

Narrow cracks do provide some useful

holds but they are best climbed in combination with conventional hand

and footholds.

In fact, it may not be possible to free climb narrow

cracks if there are no other helping holds.

The following techniques are useful in gaining some assistance

from narrow cracks:

63

OPPOSITION HOLDS:

Place the fingers of both hands in the crack

and pull in opposite directions as if trying to pull the crack apart.

The security thus provided cannot be maintained long since this is a

strenuous and fatiguing

FINGER JAM:

they will go.

tec~nique.

Place two or more fingers into the crack as far as

Then twist the entire hand to tightly wedge the fingers

within the crack.

This sounds rather rugged, but finger jams are

actually both practical and simple.

In addition to their use in

narrow cracks, they can be effectively employed in old piton scars

and similar small holes.

TOE-TIP JAM:

If one is wearing flexible-soled shoes (_climbing,

tennis or jogging shoes), it should be possible to wedge the tip of

the toes into a narrow crack.

Lower the knee to the outside, slip

the tip of the shoe in sideways, then bring the knee all the way up

and back to the crack.

The only difference between this and a true

toe jam is that a bit more courage is required to trust the body's

weight to toe-tips alone.

If narrow cracks seem overly challenging, then it would be wise

to steer altogether c1ear of wide cracks.

For it is th.e wide cracks

(_greater than 4 inches) which are most difficult of all.

They are

too wide to jam with hands or feet, and yet too narrow to squeeze the

entire body inside.

A variety of wide-crack techniques have been

developed, but they are all of limited practicality.

In the end,

it is up to the climber and his wits to come up with a successful

combi.nation of jams and wedges.

Ingenuity is thus the most important

64

element in the struggle to prevail over wide and difficult cracks.

Of the existing wide-crack techniques, the following are the

most practical and are of the greatest use to the new climber:

THUMB JAM:

The thumb may be used to jam a crack slightly too

large for a secure fist jam.

Press the edge of the hand (opposite

the thumb) firmly to one side of the crack, and wedge the uplifted

thumb to the crack•s other wall.

much of a pull.

Do not trust a thumb jam to hold

Even the best jam will provide only limited security

and it should be used primarily as an aid to balance.

HEEL/TOE JAM:

There are two popular techniques for jamming the

foot into wide cracks.

The first involves wedging the entire foot

end-to-end with the heel on one side of the crack and the toes crushed

to the other side.

A variation is useful in cracks which are not

quite wide enough to accept the full length of the foot.

force is exerted by ankles and legs, and the foot is

the crack.

11

A twisting

torqued 11 into

That is, the heel is pressed inward to one wall while

the toes are pressed outward to the other wall.

FOOT/KNEE JAM:

The twisting heel/toe jam may be improved by

pressing the knee firmly against the rock.

This gives added security

by employing two jams simultaneously (heel/toe and foot/knee).

CHIMNEY CLIMBING

When a crack widens to the point the entire body fits inside,

then the crack becomes known as a chimney.

Squeeze chimneys just

barely admit the climber; others are so wide that the climber has

difficulty bridging the gap with his body.

But whatever the width

65

of a particular chimney, the principle for climbing is the same:

the

climber stays in the chimney by pushing outwards against both walls.

Upwards progress is then made by sequentially releasing and applying

outward pressure with different portions of the body.

(Hopefully the

climber remembers not to release all outward pressure at the same

time.)

Squeeze chimneys provide a reassuring sense of security because

the harder they are to squeeze into, the harder it is to fall back

out.

Progress, however, can be painstakingly slow.

Both heel/toe

and foot/knee jams (see preceding section) may be applied to help

the ascent.

Also, one's hands can be of particular value.

Palms

are pressed (fingers pointing down) to the front wall at about waist

height.

The climber can then inch his way upwards by using both arms

and legs simultaneously.

But if the chimney is too narrow to accom-

modate these techniques, upwards motion can only be obtained by

squirming.

Then progress is truly slow.

Headway is gained much more rapidly when the chimney opens a

bit wider.

Shoulders, back, buttocks, and feet are pressed to the

back wall and the position maintained by pressing knees and hands to

the front wall.

Once again, the hands are used about waist high,

palms against the rock, and fingers pointing down.

The climber

then advances inchworm fashion by lifting his torso while knees and

feet remain jammed,

Next the torso is jammed with pressure from the

arms and hands, and the legs are raised.

In a continuing sequence

of these motions, the climber can raise himself with reasonable ease

p '

66

and speed.

Slightly wider fissures can be climbed with even greater facility

and the ideal chimney is one with a width of about three feet.

These

ideal chimneys are climbed by pressing the feet against alternate

walls in a process known as 11 Stemming 11 •

Chimney stemming appears

awkward at first, but it can be executed smoothly and speedily once

mastered.

The stemming process is as follows:

1.

Press against the front wall with the right foot raised

about hip high.

Also press against front wall with the

left hand,

2.

Raise the left foot up under the buttocks and pressing

against the back wall.

Also press against back wall with

right hand.

3.

Lift the body away from the rear wall by pushing off with

the right hand.

At the same time, raise the body by

pushing up with both legs.

4.