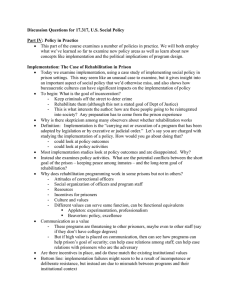

Penal Reform and Gender International Centre for Prison Studies Tool 5

advertisement