CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE ISRAELI SUMMER HOPING FOR CHANGE, CALLING FOR VIOLENCE

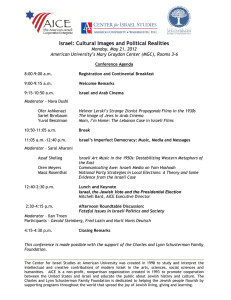

advertisement