Electoral Institutions and Electoral Cycles in Economic Development:

advertisement

Electoral Institutions and Electoral Cycles in Economic Development:

A Field Experiment of Over 3,000 US Municipalities1

Nathan M. Jensen, Associate Professor

Department of International Business

The George Washington School of Business

natemjensen@gwu.edu

Michael Findley, Associate Professor

Department of Government

University of Texas at Austin

Austin, TX 78712

mikefindley@utexas.edu

Daniel Nielson, Professor

Department of Political Science

Brigham Young University

Provo, UT 84604

dan_nielson@byu.edu

We thank Aaron Chatterji, Susan Hyde, Stephen Meier, and participants at various conference and workshop

presentations, including the International Studies Association (2013), Midwest Political Science Association

1

IRB Clearances were received on February 22, 2013 (BYU), April 2, 2013 (Washington University in St. Louis),

and May 8, 2013 (UT-Austin IRB). The research design for this experiment was registered on July 31, 2013

with the Experiments in Governance and Politics registry as study [28] 20130731, which can be found at

http://egap.org/design-registration/registered-designs/. Of the interventions registered, in this paper we

report on Hypotheses 1 and 2. In other work (Chatterji et al Forthcoming), we report on the results for

Hypothesis 3. Between the papers, we report fully on all aspects that we outlined in the original design as

stated. At the encouragement of some readers we added some additional analyses, including the investigation of

some interaction effects, but we hasten to add that we report them in addition to what was registered not in place

of. Thus the papers provide a full accounting of everything registered in the original July 31, 2013 design. We

registered an addendum for a follow-up experiment (Numbered [51] 20140131 on January 31, 2014) and those

findings will be presented elsewhere once analyzed.

Funding for this project was provided by Richard and Judy Finch and the Department of Political Science; the

College of Family, Home, and Social Sciences; the David M. Kennedy Center for International Studies at

Brigham Young University, the Weidenbaum Center and Center for New Institutional Social Sciences at

Washington University in St. Louis, and the Bannister Chair at the University of Texas at Austin.

EARLY DRAFT: COMMENTS WELCOME

1

Abstract:

The central importance of economic growth and job creation for incumbent politics leads to

considerable efforts for national and local economic development. We argue that the

proliferation of economic development policies that provide financial incentives to

individual firms provides a window into understanding how political factors shape these

economic development policies. We specifically explore how political institutions and

electoral cycles affect the allocation of incentives targeted to individual firms. We designed a

field experiment in which we approached more than 3,000 U.S. cities on behalf of a real

investor interested in relocating. We present observational and experimental evidence

showing that cities with direct elections (as opposed to appointed leaders) are dramatically

more likely to offer more and bigger incentives than cities without direct elections. Contrary

to our expectations, we do not find evidence of the greater use of incentives prior to

elections, a result that we can be fairly confident is null, although we do find that directly

elected mayors (as opposed to appointed executives) are more likely to utilize incentives. We

thus conclude that elected officials use economic incentives for political gain and that

political institutions shape this behavior, but the precise timing for offering incentives is not

important.

Keywords:

Electoral Cycles; Financial Incentives; Foreign Direct Investment; Field Experiment; Preregistration; Causal Effects; Internal Validity; External Validity

2

1. INTRODUCTION

U.S. cities spend in excess of $80 billion each year attempting to lure new investment

or to reward existing firms for expanding their production.2 Although many academics and

practitioners harshly criticize these practices as ineffective and inefficient, the policies remain

one of the most commonly utilized economic development policies. We argue that these

specific government policies, along with many other economic development tools, serve an

inventive political purpose. They help those in power to win reelection. Through the use of

incentives for credit claiming and blame avoidance, incumbent politicians manipulate levers

of accountability.

Some existing work points to the possibility that political pressures motivate the use

of economic development incentives. And yet greater theoretical precision is needed to

articulate the mechanisms linking political pressures to economic incentives, including

possible timing effects. Existing empirical studies, moreover, employ designs that do not

directly test the effects of political incentives on the behavior of the politicians themselves,

instead using purely observational data on voters or on aggregate indicators of government

activity. We are thus left with some important outstanding questions. When analyzing such a

political story at the level of the politicians themselves, do we in fact observe that electoral

pressures motivate the use of economic development incentives? If electoral pressures

matter, to what extent do political business cycles affect the incentives offered?

2

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/02/us/how-local-taxpayers-bankroll-corporations.html?_r=0

3

We contend that two political factors shape the allocation of incentives at the local

level in the United States. First, whether a municipal government has a directly elected

executive or an appointed executive may drive the use of incentives: directly elected

executives are more likely to overprovide incentives as a means of credit claiming for

economic development. Second, the literature on political business cycle and economic

voting provides clear expectations on how electoral timing shapes policy behavior:

politicians are more likely to offer incentives to companies willing to relocate prior to

municipal elections.

To directly test how electoral institutions and election timing affect economic

development policy we designed a field experiment to directly observe negotiations between

firms and local governments in the United States. For the purpose of the study, we

incorporated a financial incentive consulting company that offered site location services for

other firms. We then identified a real firm that had expressed interest in a future expansion

and signed a confidentiality agreement allowing us to collect information about local

incentives on their behalf. We hasten to add that neither we, nor our client, exchanged

money in any way. The client would receive the information we collected, and we would use

the collected information for academic research only. We were careful to communicate the

sincere interest of our client in obtaining this information, but also highlighted that the

consulting company was not negotiating a final incentive offer. We took this step, in addition

to a number of others, to ensure the ethical integrity of the experiment. We provide more

details on ethics in Section 3.3.

4

In all, we approached over 3,000 U.S. municipalities via email, collecting information

on their interest in providing incentives to our confederate firm. As outlined in our

preregistration document posted before conducting the study, the design is both

experimental and observational. Our email approach included basic information on the

investor and then randomized two manipulations, accounting for factors that we could not

manipulate such as direct or appointed executives. For cities with direct elections, we varied

whether we would announce the client firm’s relocation plans before the next local election

or after the next local election. Thus, the observational component – directly elected mayors

to test general electoral pressures – along with an experimental manipulation – timing to test

a political business cycle explanation – comprise the main focus of this paper. We also varied

the perception of the country of origin of the investor by sending our email from either our

consulting company’s US, China, or Japanese team, thereby implying the client firm was

domestic or international.3

The study produces two primary findings. Observationally, municipalities with direct

elections for mayor, as opposed to appointed city executives, are more likely to offer

incentives and provide a larger incentive package measured as dollars per job. This finding

obtains independent of the perceived country of origin of the investor (our first

experimental treatment) and is robust to a variety of model specifications, thus providing

support to arguments highlighting the political motivations behind economic development

3

We discuss the origin treatment results in this paper very briefly, but provide a fuller discussion in

Chatterji et al (Forthcoming).

5

offices. Experimentally, municipalities where a pre-election announcement of new

investment was possible were no more responsive and offered no more incentives than

municipalities where a post-election announcement would be possible. We thus find no

evidence for the prominent political business cycle argument, and the null result is specific

enough that we can be reasonably confident it is not simply the result of noise in the data.

This has important implications for a large literature that emphasizes the timing of various

incumbent behaviors relative to elections.

Given that economic development is a growth industry that significantly affects the

lives of citizens, the stakes of research in this area are very high. If incentives are offered

because they, in fact, improve the general welfare of states and cities, then that would be one

thing. But much research demonstrates that investment incentives not only do not help, but

also hurt. Understanding why, and under what conditions, the incentives are offered in the

first place is then imperative. We thus expect this field experiment to shed light on how

electoral pressures shape economic development activities as well as providing new insights

into an even larger, not to mention well accepted, literature on the power of political

business cycles. The experiment is not without its limitations and we are precise throughout

in how much we internal and external validity we claim. We especially consider these

dimensions in the sections following the survey of existing literature and the theoretical

expectations that guided the study.

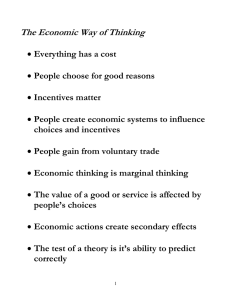

2. ELECTORAL INCENTIVE CYCLES

Economic development policies are high politics in countries, state and cities.

Economic performance is so important to incumbents that a large literature has examined

6

the existence of political business cycles--loose fiscal or monetary policy in the periods prior

to elections. A variant of this literature has focused on political budget cycles, where

governments expand spending in the period prior to elections.4

What is often less obvious is that many economic development policies are not

simply for increasing aggregate levels of economic growth and employment creation. For

example, countries, states, and cities around the world have embraced the use of targeted

incentives to attract investment to their districts. These incentives can take many forms,

including long tax holidays, worker retraining grants, low interest loans, and infrastructure

improvements all meant to sway a company’s decision to invest, expand, or stay in a given

location.

These targeted policies would be uninteresting if they were found to be effective

economic development efforts, and would give us little insights into how political factors

shape economic development policies. Unfortunately, much of the literature in political

science and economic highlights that these incentives have a very limited ability to affect

firm location choice, are exceedingly expensive relative to the benefits, and can have

unintended consequences, such as encouraging rent seeking. Thus, while the consensus is

that these policies are far from ideal and many governments have begun to regulate the use

of these incentives, their use in the United States remains common.5

4

For example, see Rogoff (1990) and Brender and Drazen 2005.

5

For one of the most comprehensive treatments of the issue see Thomas (2011).

7

The U.S. is exceptional, not only in the lack of oversight of incentives, but in the use

of incentives at the state and local level, rather than national-level incentives. This often

gives the perception of a “race to the bottom” between competing cities and the shifting of

investment across city borders with little net job creation or investment. Yet the explosion

of these policies is still puzzling given the large literature showing their limited affect on firm

investment decisions.

Given these criticisms of investment incentives, why do they persist? There are at

least two distinct theoretical arguments made it the literature. First, the argument

championed by many NGOs, is that campaign contributions and lobbying shapes

government economic policy.6 Investors, along with vested local interests (landowners,

developers, construction companies) push for economic development policies that

essentially transfer taxpayer money to firms. While the mechanisms of influence can vary,

the key is that that these local economic development policies are captured by special

interests.

A second argument is that electoral connections between economic development

policies and incumbent politicians can drive incentive use. Jensen et al (2014a) argues that

incentives can be an effective mechanism for credit claiming or blame avoidance, where a

politician can take credit for investment that was coming into her district by offering an

incentive, linking a government policy to an investment. Conversely, the politicians can

6

One example is the work of Good Jobs First (goodjobsfirst.org). This NGO has collected original data on

incentives and has begun to link these incentives to campaign contributions.

8

show effort in trying to attract investment by offering an incentive and diffusing blame if the

investment locates in another district. Using a series of survey experiments, Jensen et al

(2014a) finds evidence for possibility for credit claiming and even stronger evidence for

blame avoidance in how voters evaluate investment and incentives policies. Jensen et al

(2014b) finds that U.S. cities with electoral institutions as opposed to appointed executives

provide larger incentives.

We add to this work, but in a way that broadens theory and empirics specifically on

the role of elites in the allocation of incentives. In the United States, local governments have

the ability to offer incentives to firms, providing a clear link between government policies

and economic outcomes.

Building on work in political economy, including a rich literature on political

business cycles, we begin with the assumption that voters are imperfectly informed about the

impact of policies on outcomes.7 Unlike these political business cycle models that largely

focus on the relationship between inflation and unemployment (the Phillips Curve) we focus

on how individual policies (incentives) can be used for the purpose of job creation.

How do elites make choices on the provision of incentives for the purpose of job

creation? Ideally, politicians would use obvious cost-benefit analysis metrics, attempted to

ascertain how expensive incentives are relative to the job created. Unfortunately, Jensen et al

(2014b) note that a large number of cities don’t even conduct a simple cost-benefit analysis

of incentives.

7

Much of the political business cycle literature assumes that voters do not know a politician’s “type”.

9

Even more problematic is that even if incentives are “worth” the cost per job, it is

unclear if they are necessary to attract the investment in the first place. To give a simple

example, we can imagine politicians offering $1 per job created in incentives, which by any

cost benefit analysis would seem like a great deal. But if the investor decision isn’t swayed

by the actual incentive offer, then this $1 per job is simply a transfer to the firm. In reality,

many incentives not only fail these basic cost benefit analyzes and often fail to sway investor

decisions.

Given this debate on the effectiveness of incentives, why do we see the persistent

use of these policies? As noted by Jensen et al (2014), one potential logic is that politicians

can use these policies to claim credit for investment that was already coming to their district.

Voters actually reward politicians for violating simple cost-benefit metrics, giving politicians

more credit for investment that came with even potentially redundant incentives.

Thus, we theorize that the political use of incentives is largely shaped through

electoral mechanisms. In the United States, while there are many forms of local

government, the majority of municipalities can be classified as either mayor-council systems

or executive-manger systems.8 In the former, mayors are directly elected by voters which

leads to direct electoral pressures on mayors.9

We argue that politicians are more likely to offer more and bigger incentives when

they can use these incentives to claim credit for investment that comes to their district.

8

See Feiock et al (2003).

9

Vlaicu and Whalley (2012).

10

Following the work of Jensen et al (2014b), we argue that incentives are more likely to be

provided to directly elected governments. This particularly helps facilitate in the claiming of

credit for investment.

This leads to our first hypothesis.

Hypothesis 1: Municipalities with directly elected leaders are more likely to respond and offer

incentives than indirectly elected leaders.

This effect of electoral institutions provides a first test of how elections shape

economic development policies, but the large literature on political business cycles that we

highlighted above argues that politicians can take advantage of poorly informed or myopic

voters by expanding fiscal policies in the period prior to elections. Thus the electoral

benefits of using incentives are especially powerful in the periods prior to elections.

Politicians can induce firms to announce their investments prior to elections, maximizing the

benefits of a future job creation announcement.

Hypothesis 2: Municipalities are more likely to respond and offer incentives if the investment will be

announced prior to the next election.

Our main theory is that elected leaders are responding to electoral pressures in the allocation

of incentives. We argue that elected leaders will over-allocate incentives and this will be

most pronounced in the quarter prior to elections.

We argue that the offering of these incentives isn’t unconditional, where offering

incentives can have electoral costs. The extensive literature on the liability of foreignness in

international business highlights the many barriers that foreign firms face operating overseas

11

(Hymer 1976; Miller and Eden 2006; Zaheer 1995; Zaheer 2002 and Zaheer and

Mosakowski 1997).

One of the main mechanisms linking this “liability” are issues of nationalism on the

part of the electorate, where investments from particular countries can be seen as especially

unsavory, even if the details of the investment are otherwise completely identical. Linking

public opinion on incentives builds on recent scholarship in economics and political science

has begun to explore how public perceptions of globalization (trade, immigration and FDI)

are often shaped by non-economic factors. Hainmuller and Hiscox (2006), for example,

show that the strong positive effect of college education on support for international trade

cannot be solely attributed to the labor market impact of trade, since it holds for individuals

both in and out of the workforce. Mansfield and Mutz (2009) show that beliefs about outgroups have a dramatic effect on support for free trade. Margalit (2012) argues that the

social and cultural consequences of globalization explain much of the cross-national

evidence on resistance to economic openness. Specific to FDI, Jensen and Lindstädt (2013)

find that non-economic factors, particularly the investors’ country of origin, has a major

impact on views towards FDI.

12

We hypothesize that elected officials, especially in the period prior to their election,

will be especially sensitive to the potential backlashes against investments from a particular

set of countries. For our experiment we chose two foreign countries are potential sources of

investment that were both plausible source countries and varied in their favorability ratings

from the US public. China and Japan were both ideal countries of origin for this project in

both of these countries are major investors in the United States yet Japans had nearly double

the favorability of China. In a survey of Americans in 2007, Pew (2007) found that 42% of

Americans had a favorable opinion of China as opposed to 77% favorability of Japan. While

Chinese and Japanese investment may conjure different images to the public, or experiment

guaranteed that the investment in the China and Japan treatment were identical.10

While these public perceptions are interesting in themselves, this documented bias

against Chinese investment provides a micro-foundation for why government officials might

be less likely to respond favorably to proposals from investors based in China, specifically in

the context of these investors asking for financial incentives for the investment. It is

possible that politicians, wary of voter backlashes against using taxpayer money to support

firms from unpopular countries, may channel their resources to domestic firms. While we

could make a number of nuanced arguments on how public opinion is channeled to elected

officials, our goal it to directly test how country of origin and the liability of foreignness

shapes politician’s responses to firms. Indeed, it is possible that concerns for job creation

from any legitimate investment source might outweigh city officials’ predilection to conform

10

Jensen and Lindsteadt (2013), find that the country of origin has a major impact on FDI preferences.

13

to voter biases. This is why a field experiment is critical: it can identify treatment effects on

the behavior of the actual subject of interest behaving in her normal day-to-day routines and

thus enables stronger external validity while preserving many of the internal-validity

advantages of lab experiments.

This leads to our final three hypotheses.

Hypothesis 3a: Municipalities are more likely to respond and offer incentives if the investment is

from a US company.

Hypothesis 3b: Municipalities are more likely to respond and offer incentives if the investment is

from a Japanese company relative to a Chinese company.

Hypothesis 3c: Municipalities are least likely to respond and offer incentives if the investment is from

a Chinese company prior to their election.

3. OUR STUDY DESIGN

3.1 Experimental Context

Our study focuses on the use of incentives by U.S. municipalities. The United States

is unique compared to most developed and developing countries in their economic

development policies. In most countries a strong national investment promotion agency is

the first step in entering into a market. Although there is tremendous variation in the

capacities and professionalism of these agencies, few countries allow subnational units (states

and municipalities) to play such a direct and active role in the attraction of investment.

14

The United States only recently established a national investment promotion agency,

and it has very few tools to attract investment directly.11 This largely leaves economic

development policies to the state and local level, including the provision of incentives.

While the measurement of incentives is notoriously tricky, some have estimated that

subnational incentives in the U.S. cost as much as $80 billion per year.12

The uniqueness of the United States confines the external validity of our study.

Most localities across the world don't have the same unconstrained economic development

tools at their disposal. This study nonetheless provides an interesting laboratory to examine

the interactions between firms and governments. Specifically, the large number of U.S.

municipalities with a population above 10,000 – 3,117 in our study – provides rich variation

in city size, electoral institutions, and the ability to couple a large observational and

experimental approach in direct firm-government interactions.

3.2 Experimental Protocol

Given that we hypothesize electoral pressures may affect economic incentives, we

needed to approach mayoral economic development offices not as researchers, for which

social desirability bias would have been a concern, but rather in their actual operating

environments. In that sense, we conducted the study as a field experiment. The major

advantage of field experiments is that they maximize the realism of the experimental

11

See: http://selectusa.commerce.gov/

12

http://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/12/01/us/government-incentives.html

15

treatments (Gerber and Green 2012). Perhaps the most important element, and the most

challenging, is that subjects must not know they are participating in the experiment. In “Get

Out the Vote (GOTV)” experiments in political science, for example, researchers attempt to

mobilize potential voters who are not aware they are participating in a study.13

Field experiments thus preserve many of the internal-validity advantages of lab

experiments: because the experimental conditions are randomly assigned, in expectation all

observable and unobservable confounds are balanced across conditions. Experiments can

therefore reveal causal effects rather than just statistical correlations. Moreover, by occurring

in a natural setting where subjects behave in their normal day-to-day routines and do not

know they are being studied, field experiments also provide strong advantages in external

validity.

To maximize the realism of the study, we first identified an actual firm that was

interested in investing in another state and made an agreement to represent it with our

consulting company as detailed below. We identified a firm that was willing to provide

concrete details on their potential investment in a proposed municipality including projected

numbers on job creation and capital investment that were modeled on the operations of

existing plants. Our investment proposal exactly matched the real proposal given to us by

the client. Our client indicated that there was no latitude for changes in the amount of

capital invested or number of employees, which we honored fully in the approach emails.

Alternatively, in other field experiments subjects are made aware but only as part of what feels like their

normal everyday routine. As some international development organizations implement development programs,

for example, villages are randomly assigned to treatment after being selected in a lottery process of which they

are aware.

13

16

Our client did authorize us to vary the timing of announcement of the investment decision

and to vary attributes about our consulting company, including framing our company as

mostly representing U.S., Japanese or Chinese firms. Thus while our study does provide

insights to the decision making process of city officials and investment promotion agencies,

this is a real investor that is evaluating a relocation decision. We signed a confidentiality

agreement with the investor, assuring that the name of the individual or company would not

be used in the experiment. In return for collaborating as a confederate in the study, the

investor was offered an analysis of potential locations for the investment.

Having a real investor provide us information on their prospective investment raises

the question: will the researcher eventually be part of the negotiation of an incentive offer

between a municipality and the firm? To guard against this, we both made clear in our

approach email that all negotiations would be between the city and government and we were

only collecting information at the start of the process. We also made clear through our IRB

process that our consulting company was built solely for research purposes and does not

collect any fees or generate any revenues.

At this time, we also legally incorporated a consulting company that mimicked

existing U.S.-based investment promotion and incentive management companies. These

companies are generally small operations and often do not publish their client lists on their

websites. We incorporated our company, Globeus Consulting, as an LLC in Delaware in

2013. We created a company website and a board of consultants – all academics willing to

lend their names for the purposes of the experiment. Nathan Jensen was listed as the

company president. Three paid research assistants served as “Associates” that directly

17

contacted cities through email addresses registered through our website. We created phone

lines through Google Chat for use by our research assistants if cities required follow-up calls.

We installed web-tracking software that helped for the analysis of our experiment.

We included two forms of tracking. For every experimental treatment we provided a unique

link that routed the respondent to our website. Thus while all respondents viewed the same

websites, we could track the treatment groups based on the routing link. Second, our

website allows for IP tracking, enabling us to both track unique users and the location of the

visitor. This allows us to compare the web activity (such as pages viewed and time on the

site) by treatment group and individual.14

Our treatment consisted of directly emailing both the executive and chief of staff of

3,117 municipalities with the details of a proposed investment. As mentioned, our client

provided the plans for the future investment that would include $2 million in capital

investment and 19 full-time employees. This investment is relatively small, which has costs

and benefits for our study. Many cities may ignore an inquiry from a small investment, thus

suppressing our response rate. Yet the attraction of a small investment is plausible for all

cities in our sample, and makes it unlikely that cities expend considerable effort in the

attraction and recruitment of this investment.

On our website we created content for the purpose of our study. This included two introductions to white

papers, one on how firms can maximize incentives through job creation, the second on the use of campaign

contributions in local elections. More relevant for this paper, we created two pages, one with a discussion of

our “International Clients” and one with a discussion of our “U.S. Clients.” All of these pages had limited

content and no company names. The purpose of this content was to measure interest in specific topics.

14

18

We contacted all municipalities by email and asked them to fill out a Qualtrics

webform. We made clear that these incentive details were not binding and that we expected

cities would interact directly with the investor if their was mutual interest. We estimated that

subjects would on average spend 10-15 minutes answering the emails and given that such

requests are part of their normal day-to-day routines, they should not have incurred any new

or unexpected costs. The exact wording of our email appears below and in Appendix A and

our Qualtrics questions in Appendix B.

As outlined in the previous section, our experiment included two treatments. First,

we randomized the timing of the investment announcement, proposing a date either two

months before or one month after local elections. More specifically, we randomized the

timing of the election for all municipalities for which we could find election dates. For all

other cities, we randomized the dates.15 Second, we varied the perceived country of origin of

the investment. To vary the perceived country of origin of the investment, while minimizing

deception, we were authorized by our client to vary how we described our consulting firm.

We achieved this treatment by randomizing the source of the email, coming from either the

United States, Japan, or the China group of Globus consulting.16 The following email

prompt shows the precise wording we used where the bold words are the three potential

treatments:

15 Municipalities without election dates were treated with one of four dates corresponding to the four

quarters to the calendar year.

16 This treatment included different treatments for different groups in the first paragraph of our email

to the municipalities. The second aspect of this treatment is the email signature. Municipalities that were

treated with “China”, for example, were contacted by a research assistant that signed off as part of the “China

Client Team”.

19

“I am an associate with GLOBEUS Consulting (see our website here [insert

hyperlink]). GLOBEUS is a new consulting firm that specializes in matching cities with

prospective firms. I work in the GLOBEUS group focusing on investors based in [the

United States / Japan / China] and am contacting you to see if your city would be a good

match for a client I am representing.

Our client is considering an expansion of a manufacturing plant producing electrical

grounding products. The company is looking to make a decision and announce the

investment in [two months before next election / one month after next election]. Based

on specs from another facility, we project that the plant would create 19 full-time hourly jobs

at around $12 an hour plus benefits and 6 salaried jobs at around $40,000 per year.

The company is looking to buy or lease a 15,000 to 20,000 square-foot building. The

total investment would be $2,000,000 ($1,750,000 on building and equipment and $250,000

on other various moving expenses). Previous plants have taken 6 months from the time of

the announcement to being fully operational.

To examine the feasibility of your city for this proposed project we are asking for

you to fill out this web form (available here [insert hyperlink]) on the type of incentives you

could potentially offer this investor and what types of incentives you have offered in the

past.

As you might expect, this offer is not binding and we realize any formal offer would

require due diligence and direct interaction with our client. Our goal at this stage is to

present a detailed analysis to our client on the feasibility of relocating to your village.

We regret that we are not authorized to provide any more details about our client at

this point, but if you have any questions please feel free to contact us via email. We look

forward to your response.

[Associate Name]

[us / japan / china]_client_team@globeusconsulting.com

Selection & Incentives Associate Globeus Consulting—[U.S. / Japan / China] Client

Team Team www.globeusconsulting.com

To achieve balance across different treatment groups, prior to randomization we

block randomized using the following criteria: population (above or below the median),

form of government (council-manager or other), directly elected or appointed executive,

quarter of next election, and state.

20

3.3 Ethical Considerations

Field experimenters face a special duty to ensure the ethical treatment of their

subjects, particularly since they often withhold the knowledge that subjects are involved in a

social scientific study. Both the Belmont Report, which lays out the ethical guidelines for the

treatment of human subjects, and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’

Common Rule, which formally regulates the domain, allow for the suspension of fully

informed consent when four conditions are met: the benefits of the research are significant,

the risks are minimal, no physical or emotional pain is inflicted, and the research cannot be

carried out in another way.

Our study meets all four criteria. Governments spend billions of dollars annually on

investment incentives in the United States, but observational studies face stark limits in their

ability to identify the underlying causes with confidence. This field experiment advances

knowledge by identifying the causal effects of electoral timing and country origin, and

therefore uncovers precise estimates of treatment effects – or null results – on incentives.

Moreover, because the researchers represented an actual firm seeking to relocate, the study

presented subjects with a large potential benefit of new investment should the confederate

firm choose to relocate to one of these municipalities.

The research employed minimal deception, especially in comparison to many other

field experiments in economics and business (Bertrand and Mullainathan 2004, Butler and

Broockman 2011, Carpusor and Loges 2006, Findley et al 2014, Rooth 2008). First, we

randomly assigned the month and year communicated for when the announcement of the

relocation decision would take place. In reality, the represented firm expressed indifference

21

to the announcement date but had interest in the scientific findings and agreed to let us vary

the communicated announcement as designed. Thus, the deception was minimal. Second, we

implied in the origin treatment that the client firm originated abroad in either China or

Japan, when in reality the firm is based in the United States. The researchers contacting the

cities never directly misrepresented the firm’s origin, but the strong implication was that the

firm had an Asian identity given the researcher introduced herself/himself as working on

either the Japan or China consulting team. While no misdirection would be preferable, we

could not conceive of a method of holding constant all relevant firm details while varying

country origin except through the method employed. Because learning about potential

discrimination against foreign firms in investment incentives is important, we concluded that

the benefits of the research outweighed the minor costs of the misdirection.

Our experiment qualifies as exempt from human subjects approval since

organizations are not considered as human subjects (and no data were collected on any

individual) and public officials are a special class of subjects not protected by IRBs (based on

the Common Rule). Despite this general exemption, as noted all three institutions’

institutional review boards cleared our proposal. And more important than simple clearance,

however, we conscientiously made a number of important choices to minimize deception

and protect both the subjects and our client.

3.4 Preregistration of the Research Design

We pre-registered the research design with the Experiments in Governance and Politics

(EGAP) Network (www.e-gap.org) on July 31, 2013, prior to the execution of the experiment

22

in August 2013. The registration documents were embargoed until September, 2014 to avoid

detection in the field experiment, but now they are currently available. We registered

substantial information including names, affiliations, contact information, study background,

hypotheses, expected analysis procedures, who will carry out the research.

4. ANALYSIS

We follow the analysis protocol described in our pre-registration document, focusing

on three outcome indicators. First, we examined response rates to our inquiry in the form of

filling out the online web form. Second, we considered whether the subject indicated that the

respondent city would be willing to offer financial incentives to our client firm. Finally, we

present evidence about actual offers provided to the consulting company on the size of

incentives measured as the log of grant dollars per job.

In Table 1 we present a total of 8 models using response rate as the dependent

variable. While the experiment assures balances across groups for the experimental

treatments (election timing and country of origin) our hypothesis on the form of

government requires us to include control variables because we were unable to manipulate

form of government. We specifically include a variable for the population of municipality,

since mayoral forms of government have a different population distribution than councilmayors, and dummies for region and states. The odd models (1, 3, 5, and 7) include regional

dummies as control variables and the even models include state fixed effects.

<Insert Table 1 about here>

23

Models 1 and 2 are our primary tests of the form of government, where we merged

our experimental data with survey data from the International City/County Management

Association (ICMA). This survey asked city managers a battery of questions, including the

formal form of government. Unfortunately the voluntary nature of the survey means poor

coverage of our sample of cities. As a secondary test we hand collected data on the presence

of direct executive elections for most of our sample of 3,000 municipalities. This increased

sample size comes with a considerable costs. Many cities with council-manager institutions,

and thus a strong appointed executive, also have a directly elected mayor, creating challenges

for separating the two. These caveats aside, we include tests of how direct elections shape

response rates in Models 3 and 4. We find little impact of local institutions on response rates.

Only in model 3 do we find that elected officials have a lower propensity to respond,

although this result is not robust to state fixed effects.

In Models 5 and 6 we include our randomized election timing variable, coded as 1

for investments after local elections and 0 otherwise. Our expectation, following the

political business cycle argument, was that response rates would be lower for the postelection investments. We find no evidence that elections have a direct impact on response

rates in either of these models.

Building on Chatterji et al (Forthcoming) we find some evidence of lower responses

to foreign investors relative to domestic investors. Responses by individuals interacting with

the Japan and China client team had lower response rates, although only the Japanese result

is statistically significant.

24

We replicate these same sets of tests for the other dependent variables, in Tables 2

and 3. In Table 2 we coded the dependent variable as 1 if the municipality provided us

details on a potential incentive offer through the Qualtrics form and 0 otherwise. In Table 3

we estimate OLS regressions with the log of grant dollars offered as the dependent variable.

<Insert Table 2 about here>

<Insert Table 3 about here>

The results from Table 2 and 3 are generally consistent with our substantive findings

from Table 1. First, we find that the form of government, as measured in the first two

models of all three tables, has a major impact on incentives. Municipalities with mayorcouncil institutions are more likely to offer incentives and the sizes of the incentives are

substantially larger.

The results using our own collected data on the presence of direct elections are

mixed. We find that municipalities with direct elections have a lower propensity to offer

incentives, but this has no impact on the size of incentive offers. We can only speculate on

the meanings of these results given measurement error inherent in this variable.

The results on the timing of elections, our third set of results in each table, are

clearer. We find absolutely no support for incentive offers being affected by the timing of

an investment in the period immediately before or after elections.17

17

Interestingly, we do find lower responses to firms that would invest in the first quarter. This

finding was not anticipated yet is relatively consistent across tests.

25

We present our results on the country of origin for completeness, but note that these

results have been presented at Chatterji et al (Forthcoming). We find no major impact of the

country of origin on incentives. While municipalities were less likely to respond to emails

from the Japan Client team, this has no impact on the offering of incentives measured

dichotomously or through log dollars.

The findings from the experimental conditions, the timing of investment and

country of origin, are both relatively clear null results. While null results are often not

celebrated, it is worth discussing the implications of these results. Importantly, large

literatures on political business cycles and the liabilities of being foreign for investment

purposes point towards clear expectations of results. And yet we do not find supporting

evidence for either of these theories. We may thus need to reconsider conventional wisdom,

at least in this important context.

Our non-experimental finding on municipal institutions is worth exploring further.

In Table 4 we present additional tests where we include the measure of government type

along with our treatment on the country of origin. We find similar results. Mayor-council

institutions are associated with more and bigger incentive offers.

<Insert Table 4 about here>

As a final test of Hypothesis 3c we include interactions between the timing of the

election and the country of origin of the investment. Those results are reported in Table 5

Unsurprisingly at this point, we find no evidence for this hypothesis.

<Insert Table 5 about here>

26

In summary, our results provide strong support for Hypothesis 1, that local

institutions shape incentive behavior. But we find no support for the other hypotheses.

5. CONCLUSION

The creation of jobs remains one of the most important policies for government

officials, yet the policies to best create high quality jobs remains elusive. Governments

around the world, and the United States in particular, have turned to targeted financial

incentives to individual firms. Much of the existing literature has pointed to the

inefficiencies of these policies, and the tremendous opportunities for corruption or other

malfeasance given both the lack of transparency and oversight of many of these programs.

We argue that the use of these programs can be largely understood by examining the

political benefits of incentives. Building on existing work on electoral pandering along with

political budget cycles we argue that politicians facing direct elections (as opposed to

appointment) are motivated to provide more incentives (in number and amount) and this is

heighted in the periods prior to reelection. Building work on the “liability of foreignness”,

we also argue that the willingness of electoral politicians to offer generous incentives is

tempered by the country of origin of the investor. Governments are less likely to offer these

incentives to foreign firms, especially those from unpopular countries.

Exploring how these factor shape incentives is extremely difficult with observational

data. For example, simply examining data the incentives that have been accepted by firms (if

available) suffers from serious selection bias. We only observe the incentives that were both

offered and accepted by firms. Equally problematic is the difficulty in comparing the

incentives offered to firms of different sizes, sectors, and from different home countries.

27

We side-step many of these hurdles through an experimental approach where

contact 3,000 U.S. municipalities on behalf of a confederate firm. This allows for the perfect

comparison across cities since every city was interacting with a firm in the same industry and

the same size. The only aspects that we varied in our approach was the timing of the

investment (before or after elections) and the perceived country of origin of the investment

(a U.S. company, a Chinese company, or a Japanese company).

As part of our commitment to an ethical experiment, not only were we careful in

minimizing deception in our study, we also pre-registered our protocol and analysis plan.

Our specific hypotheses were pre-specified before the fielding of our experiment, and data

collection protocols and coding decisions were made prior to data collection. Thus we tied

our own hands from any “data mining” or “fishing”.

Our main results are varied. Our hypotheses on both the electoral timing and the

country of origin of the investors were not supported in our analysis. We found that

municipal leaders and economic development professionals had very similar responses to

firms they perceived to be from difference countries and they were no more receptive to

investments before or after elections.

On the contrary, we found that the form of municipal government had a dramatic

impact on the allocation of incentives. Municipalities with directed elected mayors in

“mayor-council” systems were more likely to offer incentives and these incentives offers

were substantially larger than their appointed counterparts in “council-manager” systems.

These finds had important implications for the study of incentives, and have broader

implications for the examination of the political economy of economic development

28

policies. Our findings suggests that political institutions, rather than the electoral calendar or

popularity of the investor, have a dramatic impact on economic development policies. One

potential conjecture is that political institutions help shape the formation of economic

development policies, such as the size of incentives, and possibly even their oversight. As

shown by Jensen et al (2014b) using observational data, political institutions affect whether

or not municipalities required a cost benefit analysis or have strong job creation criteria as

part of an incentive offer. Our experimental results are consistent with these findings, where

we find that the aggregate dollar per job amount is dramatically higher in mayor-council

institutions, the same institutions that have weaker oversight and performance criteria. This

finding, while specific to incentives, could be generalizable to other policy settings.

29

References

Balabanis, George, and Adamantios Diamantopoulos. 2004. Domestic Country Bias,

Country-of-Origin Effects, and Consumer Ethnocentrism: A Multidimensional

Unfolding Approach. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32 (1):80-95.

Baughn, C. C. and Yaprak, A. 1993. Product-Country Images: Impact and Role in

International Marketing. New York: Business Press

Bertrand, Marianne, and Sendhil Mullainathan. 2004. Are Emily and Greg more employable

than Lakisha and Jamal? A field experiment on labor market discrimination.

American Economic Review 94, no. 4: 991-1013.

Bilkey, Warren J., and Erik Nes. 1982. Country of Origin Effects on Consumer Evaluations.

Journal of International Business Studies 13 (1):89-99.

Brender, Adi and Allan Drazen. 2005. Political budget cycles in new versus established

democracies. Journal of Monetary Economics 52 (7): 1271-1295.

Butler, Daniel M. and David E. Broockman. 2011. Do Politicians Racially Discriminate

Against Constituents? A Field Experiment on State Legislators. American Journal of

Political Science 55 (3): 463-477.

Carpusor, Adrian G., and William E. Loges. 2006. Rental discrimination and ethnicity in

names. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 36, no. 4: 934-952.

Caves RE. 1971. Industrial corporations: the industrial economics of foreign investment.

Economica 38. 1 - 27.

Chatterji, Aaron, Michael Findley, Nathan M. Jensen, Stephan Meier, and Daniel Nielson.

Forthcoming. Field Experiments in Strategy. The Strategic Management Journal

Dickersin, Kay. 1990. The Existence of Publication Bias and Risk Factors for its Occurrence.

Journal of the American Medical Association 263(10): 1385-1389.

Findley, Michael G., Daniel L. Nielson, and J.C. Sharman. 2014. Global Shell Games:

Experiments in Transnational Relations, Crime, and Terrorism. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Gerber, Alan, and Neil Malhotra. 2008. "Do Statistical Reporting Standards Affect What is

Published: Publication Bias in Two Leading Political Science Journals." Quarterly

Journal of Political Science 3: 313-326.

Gerber, Alan, Neil Malhotra, Conor Dowling, and David Doherty. 2010. Publication Bias in

Two Political Behavior Literatures. American Politics Research 38(4): 591-613.

Gerber, Alan, and Don Green. 2012. Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation. W.W.

Norton.

Glewwe, P., and Michael Kremer. 2006. Schools, Teachers, and Education Outcomes in

Developing Countries. Handbook of Economics Education 2: 945-1017.

Hainmueller, Jens, and Michael J. Hiscox. 2006. Learning to Love Globalization: Education

and Individual Attitudes Toward International Trade. International Organization 60

(2):469-98.

Hymer, S. 1976. The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Foreign Direct Investment,

Cambridge. MA: MIT Press.

30

Ioannidis, J. 1998. Effect of the Statistical Significance of Results on the Time to

Completion and Publication of Randomized Efficacy Trials. Journal of the American

Medical Association 279(4): 281-286.

Jensen, Nathan M. and René Lindstädt. 2013. Globalization with Whom: ContextDependent Foreign Direct Investment Preference. Working Paper.

Jensen, Nathan M., Edmund Malesky and Matthew Walsh. 2014. Competing for Global

Capital or Local Voters? The Politics of Business Location Incentives. Working

Paper.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Diana C. Mutz. 2009. Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest,

Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety. International Organization 63 (3):425-57.

Margalit, Yotam. 2012. Lost in Globalization: International Economic Integration and the

Sources of Popular Discontent. International Studies Quarterly 56 (3):484-500.

Mansfield, Edward D., and Diana C. Mutz. 2009. Support for Free Trade: Self-Interest,

Sociotropic Politics, and Out-Group Anxiety. International Organization 63 (3):425-57.

Margalit, Yotam. 2012. Lost in Globalization: International Economic Integration and the

Sources of Popular Discontent. International Studies Quarterly 56 (3):484-500.

Mezias, John M. Identifying liabilities of foreignness and strategies to minimize their effects:

the case of labor lawsuits judgments in the United States. Strategic Management Journal

23 no 2: 229-244.

Miller, S. and L. Eden. 2006. Local Density and Foreign Subsidiary Performance. Academy of

Management Journal 49 (2): 341-355.

Miller, Stewart R. and Arvind Parkhe. 2002. Is there a liability of foreignness in global

banking? An empirical test of banks’ X-efficiency. Strategic Management Journal 23 no

1: 55-75.

Mitchell, J. Robert, Dean A. Shepherd, and Mark P Sharfman. 2011. “Erratic Strategic

Decisions: When and Why Managers are Inconsistent in Strategic Decision Making.”

Strategic Management Journal 32: 683-704.

Nachum, Lilach. 2003. Liability of foreignness in global competition? Financial service

affiliates in the city of London. Strategic Management Journal 24 no 12: 1187-1208.

O’Rourke, Kevin H., and Richard Sinnott. 2006. The Determinants of Individual Attitudes

towards Immigration. European Journal of Political Economy 22 (4):838-61.

Pandya, Sonal S. and Rajkumar Venkatesan. 2013. French Roast: International Conflict and

Consumer Boycotts – Evidence from Supermarket Scanner Data. Working Paper.

Peterson, Robert A., and Alain J. P. Jolibert. 1995. A Meta-Analysis of Country-Of-Origin

Effects. Journal of International Business Studies 26 (4):883-900.

Pew Center. 2007, Pew Global Attitudes Survey. <http://tinyurl.com/6tp2oka>

Rafaeli, Anat, Yael Sagy, and Rellie Derfler-Rozin. 2008. Logos and Initial Compliance: A

Strong Case of Mindless Trust. Organization Science 19(6): 845-859.

Rogoff, Kenneth. 1990. Equilibrium Political Budget Cycles, American Economic Review

80: 21-36.

Rooth, Dan-Olof. 2009. Obesity, attractiveness, and differential treatment in hiring. The

Journal of Human Resources 44, no. 3: 710-735.

Shimp, Terence A., and Subhash Sharma. 1987. Consumer Ethnocentrism: Construction and

Validation of the CETSCALE. Review of Marketing Research. 24 (3):280-89.

31

Thomas, Kenneth P. 2011. Investment Incentives and the Global Competition for Capital. New

York: Palgrave Macmillian.

Usunier, Jean-Claude, and Ghislaine Cestre. 2007. Product Ethnicity: Revisiting the Match

Between Products and Countries. Journal of International Marketing 15 (3):32–72.

Verlegh, Peeter. W. J., and Jan Benedict E. M. Steenkamp. 1999. A Review and MetaAnalysis of Country-of-Origin Research. Journal of Economic Psychology 20 (5):521-46.

Zaheer, Srilata. 1995. Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal

38: 341-63.

Zaheer, Srilata. 2002. The Liability of Foreignness, Redux: A Commentary. Journal of

International Management 8(3): 351-358.

Zaheer, Srilata and E. Mosakowski. 1997. The dynamics of the liability of foreignness: A

global study of survival in financial services. Strategic Management Journal 18: 439-64.

32

Appendix A: Approach Email

“I am an associate with GLOBEUS Consulting (see our website here [insert

hyperlink]). GLOBEUS is a new consulting firm that specializes in matching cities with

prospective firms. I work in the GLOBEUS group focusing on investors based in [the

United States / Japan / China] and am contacting you to see if your city would be a good

match for a client I am representing.

Our client is considering an expansion of a manufacturing plant producing electrical

grounding products. The company is looking to make a decision and announce the

investment in [two months before next election / one month after next election]. Based on

specs from another facility, we project that the plant would create 19 full-time hourly jobs at

around $12 an hour plus benefits and 6 salaried jobs at around $40,000 per year.

The company is looking to buy or lease a 15,000 to 20,000 square-foot building. The

total investment would be $2,000,000 ($1,750,000 on building and equipment and $250,000

on other various moving expenses). Previous plants have taken 6 months from the time of

the announcement to being fully operational.

To examine the feasibility of your city for this proposed project we are asking for

you to fill out this web form (available here [insert hyperlink]) on the type of incentives you

could potentially offer this investor and what types of incentives you have offered in the

past.

As you might expect, this offer is not binding and we realize any formal offer would

require due diligence and direct interaction with our client. Our goal at this stage is to

present a detailed analysis to our client on the feasibility of relocating to your village.

We regret that we are not authorized to provide any more details about our client at

this point, but if you have any questions please feel free to contact us via email. We look

forward to your response.

[Associate Name]

[us / japan / china]_client_team@globeusconsulting.com

Selection & Incentives Associate Globeus Consulting—[U.S. / Japan / China] Client Team

Team www.globeusconsulting.com

33

Appendix B: Qualtrics Question

7/30/13

Qualtrics Survey Software

Globeus Consulting

Selection & Incentives Department

Introduction

This data you enter into this webform will be used by our client to narrow down their location decision. Your answers

are not binding, but any concrete details you can provide will help us evaluate the feasibility of your ${e://Field/type} as

a site for the plant relocation.

In this form we will ask about:

a) Grants and loans for relocation provided on a per job basis. b) Tax abatements (on property and earnings taxes).

c) Any other local incentives provided. Grants and Loans

Please indicate the availability of grants and loans.

Local grant dollars for relocation

(dollars per job)

Local loans for relocation (dollars

per job)

Please enter additional comments or information about grants and loans below.

Real Property Tax

Does your ${e://Field/type} have local real property taxes?

Yes

No

Please indicate below the local real property tax abatement or refund your ${e://Field/type} is able to offer.

Not

Applicable

0

10

20

30

40

50

https://s.qualtrics.com/ControlPanel/Ajax.php?action=GetSurveyPrintPreview&T=2DBJY8

34

60

70

80

90

100

1/4

35

36

Table 1: Response rate with state and region dummies IVs (1) (2) (3) (4) Government 0.077 0.091 — — type (0.097) (0.116) -­‐0.304** -­‐0.266 Elected — — (0.146) (0.171) After — — — — election (5) (6) (7) (8) — — — — — — — — -­‐0.027 (0.06) -­‐0.032 (0.061) — — -­‐0.145** (0.072) -­‐0.083 (0.071) 0.186*** (0.06) -­‐0.456*** (0.17) 0.011 (0.068) -­‐0.292 (0.222) -­‐0.421*** (0.0996) 0.132 (0.085) 0.078 (0.086) -­‐0.145** (0.073) -­‐0.083 (0.072) 0.197*** (0.062) -­‐0.671*** (0.203) -­‐0.18 (0.113) -­‐0.1 (0.289) Japan — — — — — — China — — — — — — 0.143* (0.086) -­‐0.594** (0.24) 0.079 (0.093) -­‐0.48 (0.397) -­‐0.65*** (0.189) 0.064 (0.115) 0.093 (0.112) 0.168* (0.09) -­‐0.799*** (0.294) -­‐0.038 (0.177) -­‐0.16 (0.479) 0.197*** (0.06) -­‐0.467*** (0.17) -­‐0.013 (0.069) -­‐0.306 (0.222) -­‐0.494*** (0.107) 0.138 (0.085) 0.087 (0.086) 0.207*** (0.062) -­‐0.683*** (0.204) -­‐0.219* (0.115) -­‐0.11 (0.288) 0.209*** (0.062) -­‐0.514*** (0.178) -­‐0.011 (0.072) -­‐0.312 (0.222) -­‐0.516*** (0.111) 0.141 (0.086) 0.092 (0.087) 0.211*** (0.064) -­‐0.743*** (0.215) -­‐0.243** (0.122) -­‐0.134 (0.29) NO YES NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐0.984*** (0.131) -­‐0.934 (0.634) -­‐0.744*** (0.161) -­‐0.16 (0.485) -­‐1.041*** (0.083) -­‐0.404 (0.457) -­‐0.967*** (0.086) -­‐0.374 (0.457) Population 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter Region 1 (Northeast) Region 2 (Midwest) Region 3 (South) State dummies Constant — — — — — — — — — — — — Pseudo R-­‐

0.03 0.054 0.028 0.061 0.03 0.061 0.028 0.061 squared N 1276 1230 2690 2684 2527 2513 2690 2684 Notes: Coefficients of probit regressions. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. Dependent variable: 1 responded and 0 otherwise. Coefficients for fixed effects for individual states were included in the regression but omitted here for simplicity in presentation. The 4th Quarter is the omitted category for the quarterly dummies and Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 37

Table 2: Incentive offered with state and region dummies IVs (1) (2) (3) (4) Government 0.197* 0.265* — — type (0.114) (0.14) -­‐0.437*** -­‐0.382** Elected — — (0.166) (0.194) After — — — — election (5) (6) (7) (8) — — — — — — — — -­‐0.007 (0.07) -­‐0.02 (0.073) — — -­‐0.022 (0.081) -­‐0.096 (0.083) 0.172** (0.069) -­‐0.444** (0.209) -­‐0.032 (0.078) -­‐0.197 (0.246) -­‐0.288** (0.122) 0.318*** (0.1) 0.232** (0.102) -­‐0.021 (0.085) -­‐0.102 (0.086) 0.189*** (0.072) -­‐0.765*** (0.269) -­‐0.198 (0.133) 0.052 (0.334) Japan — — — — — — China — — — — — — 0.13 (0.099) -­‐0.522* (0.285) 0.003 (0.105) -­‐0.537 (0.498) -­‐0.362 (0.229) 0.322** (0.136) 0.347*** (0.132) 0.175* (0.105) -­‐0.875** (0.379) -­‐0.176 (0.211) -­‐0.328 (0.573) 0.189*** (0.07) -­‐0.464** (0.211) -­‐0.062 (0.078) -­‐0.204 (0.246) -­‐0.403*** (0.133) 0.326*** (0.1) 0.246** (0.103) 0.205*** (0.073) -­‐0.804*** (0.274) -­‐0.246* (0.136) 0.06 (0.332) 0.205*** (0.072) -­‐0.566** (0.231) -­‐0.079 (0.082) -­‐0.218 (0.246) -­‐0.405*** (0.14) 0.335*** (0.101) 0.262** (0.103) 0.219*** (0.076) -­‐0.923*** (0.302) -­‐0.274* (0.145) 0.032 (0.335) NO YES NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐1.59*** (0.16) -­‐0.838** (0.34) -­‐1.062*** (0.185) -­‐0.891 (0.607) -­‐1.505*** (0.101) -­‐1.269** (0.581) -­‐1.446*** (0.103) -­‐1.23** (0.58) Population 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter Region 1 (Northeast) Region 2 (Midwest) Region 3 (South) State dummies Constant — — — — — — — — — — — — Pseudo R-­‐

0.034 0.078 0.034 0.084 0.035 0.087 0.031 0.083 squared N 1281 1164 2697 2614 2534 2452 2697 2614 Notes: Coefficients of probit regressions. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. Dependent variable: 1 incentive offered and 0 otherwise. Coefficients for fixed effects for individual states were included in the regression but omitted here for simplicity in presentation. The 4th Quarter is the omitted category for the quarterly dummies and Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 38

Table 3: Logged dollars with state and region dummies IVs (1) (2) (3) (4) Government 0.237** 0.241** — — type (0.095) (0.108) 0.035 -­‐0.03 Elected — — (0.11) (0.132) After — — — — election (5) (6) (7) (8) — — — — — — — — -­‐0.046 (0.05) -­‐0.05 (0.049) — — -­‐0.004 (0.058) 0.017 (0.057) 0.038 (0.048) -­‐0.138 (0.114) 0.055 (0.056) -­‐0.253 (0.168) -­‐0.197*** (0.074) -­‐0.073 (0.071) 0.026 (0.072) -­‐0.006 (0.057) 0.011 (0.057) 0.039 (0.048) -­‐0.224* (0.123) -­‐0.073 (0.086) -­‐0.133 (0.23) Japan — — — — — — China — — — — — — -­‐0.054 (0.085) -­‐0.214 (0.193) 0.079 (0.095) -­‐0.322 (0.343) -­‐0.172 (0.153) -­‐0.145 (0.117) 0.128 (0.114) -­‐0.066 (0.085) -­‐0.306 (0.207) -­‐0.269* (0.161) -­‐0.248 (0.442) 0.037 (0.048) -­‐0.138 (0.114) 0.058 (0.057) -­‐0.253 (0.168) -­‐0.19** (0.077) -­‐0.075 (0.071) 0.025 (0.072) 0.041 (0.049) -­‐0.226* (0.123) -­‐0.078 (0.088) -­‐0.133 (0.23) 0.031 (0.051) -­‐0.148 (0.12) 0.058 (0.061) -­‐0.255 (0.172) -­‐0.186** (0.081) -­‐0.083 (0.074) 0.024 (0.074) 0.035 (0.052) -­‐0.24* (0.13) -­‐0.089 (0.096) -­‐0.142 (0.239) NO YES NO YES NO YES NO YES 0.139 (0.131) 9.258*** (1.422) 0.179 (0.124) -­‐0.011 (1.215) 0.243*** (0.07) 3.16*** (0.878) 0.209*** (0.071) -­‐0.051 (1.21) Population 1st Quarter 2nd Quarter 3rd Quarter Region 1 (Northeast) Region 2 (Midwest) Region 3 (South) State dummies Constant — — — — — — — — — — — — Adjusted R-­‐

0.01 0.052 0.004 0.022 0.003 0.021 0.003 0.022 squared N 1281 1284 2697 2700 2534 2537 2697 2700 Notes: Coefficients of OLS regressions. Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. Dependent variable: logged dollars offered as incentives. Coefficients for fixed effects for individual states were included in the regression but omitted here for simplicity in presentation. The 4th Quarter is the omitted category for the quarterly dummies and Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 39

Table 4: Response rate, incentive offered, and logged dollars with multiple IVs IVs Response rate Incentive offered Logged dollars Government 0.077 0.092 0.198* 0.266* 0.237** 0.242** type (0.098) (0.117) (0.114) (0.141) (0.095) (0.108) -­‐0.193* -­‐0.191* 0.025 0.022 -­‐0.002 0.004 Japan (0.101) (0.104) (0.114) (0.12) (0.0996) (0.098) -­‐0.071 -­‐0.069 -­‐0.045 -­‐0.056 0.039 0.053 China (0.098) (0.101) (0.115) (0.121) (0.099) (0.098) 0.146* 0.172* 0.13 0.175* -­‐0.055 -­‐0.067 Population (0.086) (0.09) (0.099) (0.105) (0.085) (0.085) -­‐0.59** -­‐0.804*** -­‐0.519* -­‐0.873** -­‐0.214 -­‐0.304 1st Quarter (0.24) (0.295) (0.284) (0.378) (0.193) (0.207) 0.08 -­‐0.027 0.002 -­‐0.179 0.08 -­‐0.268* 2nd Quarter (0.093) (0.177) (0.105) (0.211) (0.095) (0.161) -­‐0.478 -­‐0.167 -­‐0.543 -­‐0.336 -­‐0.321 -­‐0.245 rd

3 Quarter (0.395) (0.477) (0.4999) (0.576) (0.343) (0.443) Region 1 -­‐0.659*** -­‐0.361 -­‐0.173 — — — (Northeast) (0.19) (0.229) (0.153) Region 2 0.064 0.323** -­‐0.146 — — — (Midwest) (0.115) (0.136) (0.117) 0.095 0.349*** 0.127 Region 3 (South) — — — (0.112) (0.132) (0.114) State dummies NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐0.901*** -­‐0.873 -­‐1.585*** -­‐0.823** 0.127 9.258*** Constant (0.142) (0.637) (0.172) (0.345) (0.142) (1.423) Pseudo R-­‐

0.033 0.057 0.034 0.079 0.009 0.051 squared N 1276 1230 1281 1164 1281 1284 Notes: Coefficients of Probit models (for response rate and incentive offered) and OLS regression (for logged dollars). Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. The 4th Quarter is the omitted category for the quarterly dummies and Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 40

Table 5: Response rate, incentive offered, and logged dollars with interactions IVs Response rate Incentive offered Logged dollars -­‐0.026 -­‐0.037 0.017 0.003 0.01 -­‐0.003 After election (0.074) (0.075) (0.084) (0.088) (0.061) (0.061) -­‐0.122 -­‐0.125* 0.008 0.004 0.005 0.005 Japan (0.074) (0.076) (0.085) (0.088) (0.061) (0.061) -­‐0.063 -­‐0.073 -­‐0.024 -­‐0.035 0.11 0.093 China (0.097) (0.099) (0.113) (0.118) (0.08) (0.08) After election × -­‐0.004 0.014 -­‐0.078 -­‐0.071 -­‐0.168 -­‐0.141 China (0.128) (0.131) (0.149) (0.156) (0.105) (0.105) 0.211*** 0.212*** 0.204*** 0.219*** 0.03 0.035 Population (0.062) (0.064) (0.072) (0.076) (0.051) (0.052) -­‐0.512*** -­‐0.747*** -­‐0.565** -­‐0.918*** -­‐0.153 -­‐0.244* 1st Quarter (0.178) (0.215) (0.229) (0.2999) (0.12) (0.13) -­‐0.008 -­‐0.236* -­‐0.08 -­‐0.274* 0.058 -­‐0.087 nd

2 Quarter (0.072) (0.122) (0.082) (0.146) (0.061) (0.096) -­‐0.305 -­‐0.127 -­‐0.223 0.023 -­‐0.256 -­‐0.139 3rd Quarter (0.222) (0.29) (0.247) (0.336) (0.172) (0.239) Region 1 -­‐0.513*** -­‐0.403*** -­‐0.185** — — — (Northeast) (0.111) (0.14) (0.081) Region 2 0.142* 0.335*** -­‐0.083 — — — (Midwest) (0.086) (0.101) (0.074) 0.093 0.262** 0.023 Region 3 (South) — — — (0.087) (0.103) (0.074) State dummies NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐0.983*** -­‐0.365 -­‐1.4996*** -­‐1.252** 0.205** 3.089*** Constant (0.095) (0.46) (0.114) (0.583) (0.079) (0.88) Pseudo R-­‐

0.031 0.062 0.035 0.088 0.003 0.021 squared N 2527 2513 2534 2452 2534 2537 Notes: Coefficients of Probit models (for response rate and incentive offered) and OLS regression (for logged dollars). Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. The 4th Quarter is the omitted category for the quarterly dummies and Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 41

Appendix Table A1: Response rate, incentive offered, and logged dollars with government type interactions IVs Response rate Incentive offered Logged dollars -­‐0.305 -­‐0.341 0.334 0.432 0.334 0.384 Government type (0.264) (0.347) (0.39) (0.509) (0.278) (0.347) Government type × -­‐0.059 -­‐0.11 -­‐0.049 -­‐0.06 0.038 0.017 Population (0.189) (0.201) (0.221) (0.237) (0.183) (0.183) Government type × -­‐0.1 -­‐0.297 -­‐0.049 -­‐0.329 -­‐0.132 -­‐0.261 1st Half (0.201) (0.236) (0.231) (0.276) (0.196) (0.216) Government type × 0.126 -­‐0.098 -­‐0.374 -­‐0.47 -­‐0.203 -­‐0.199 Northeast (0.415) (0.534) (0.54) (0.704) (0.352) (0.42) Government type × 0.574** 0.837** -­‐0.19 0.027 -­‐0.134 -­‐0.074 Midwest (0.282) (0.379) (0.396) (0.528) (0.297) (0.375) Government type × 0.65** 0.683* 0.192 0.089 0.101 0.08 South (0.303) (0.408) (0.424) (0.568) (0.314) (0.3997) 0.192 0.247 0.163 0.21 -­‐0.081 -­‐0.077 Population (0.159) (0.172) (0.189) (0.203) (0.151) (0.152) 0.079 0.0002 -­‐0.017 -­‐0.061 0.125 -­‐0.067 1st Half (0.172) (0.249) (0.199) (0.296) (0.165) (0.219) Region 1 -­‐0.874*** -­‐0.129 -­‐0.027 — — — (Northeast) (0.301) (0.429) (0.287) Region 2 -­‐0.344 0.51 -­‐0.008 — — — (Midwest) (0.251) (0.367) (0.267) Region 3 -­‐0.455* 0.191 0.062 — — — (South) (0.277) (0.401) (0.288) State dummies NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐0.675*** -­‐0.775 -­‐1.726*** -­‐0.897** 0.037 9.11*** Constant (0.236) (0.654) (0.365) (0.381) (0.252) (1.457) Government type 7.15 8.89 5.69 5.72 1.48 1.23 interactions F-­‐test [0.307] [0.18] [0.459] [0.456] [0.181] [0.286] Pseudo R-­‐squared 0.027 0.056 0.031 0.077 0.007 0.052 N 1276 1230 1281 1164 1281 1281 Notes: Coefficients of Probit models (for response rate and incentive offered) and OLS regression (for logged dollars). Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. The “Quarter” variables are combined to avoid biased standard errors; they appear here as 1st and 2nd Half (where 2nd Half is the omitted variable). Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. P-­‐values for joint significance are shown in brackets under the F-­‐statistics. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 42

Table A2: Response rate, incentive offered, and logged dollars with after election interactions IVs Response rate Incentive offered Logged dollars -­‐0.052 -­‐0.06 -­‐0.007 0.015 -­‐0.064 -­‐0.069 After election (0.156) (0.159) (0.19) (0.201) (0.13) (0.129) After election × 0.034 0.027 0.007 -­‐0.02 0.006 0.028 Population (0.124) (0.127) (0.144) (0.151) (0.102) (0.101) After election × 1st -­‐0.107 -­‐0.113 -­‐0.065 -­‐0.045 0.079 0.066 Half (0.135) (0.14) (0.156) (0.163) (0.113) (0.113) After election × 0.769*** 0.804*** 0.821** 0.922** 0.09 0.086 Northeast (0.244) (0.255) (0.334) (0.378) (0.161) (0.161) After election × -­‐0.009 0.007 -­‐0.032 -­‐0.061 -­‐0.058 -­‐0.075 Midwest (0.169) (0.172) (0.1997) (0.209) (0.145) (0.144) After election × -­‐0.108 -­‐0.096 -­‐0.109 -­‐0.146 -­‐0.027 -­‐0.023 South (0.17) (0.176) (0.203) (0.217) (0.145) (0.144) 0.187** 0.195** 0.198* 0.229** 0.027 0.02 Population (0.088) (0.091) (0.103) (0.108) (0.072) (0.072) -­‐0.012 -­‐0.309** -­‐0.093 -­‐0.389** -­‐0.007 -­‐0.168* 1st Half (0.094) (0.13) (0.109) (0.156) (0.08) (0.1) Region 1 -­‐0.976*** -­‐0.941*** -­‐0.225** — — — (Northeast) (0.196) (0.284) (0.114) Region 2 0.189 0.387*** -­‐0.033 — — — (Midwest) (0.118) (0.14) (0.102) Region 3 0.141 0.312** 0.026 — — — (South) (0.118) (0.141) (0.103) State dummies NO YES NO YES NO YES -­‐1.05*** -­‐0.385 -­‐1.523*** -­‐1.29** 0.241*** 3.127*** Constant (0.11) (0.469) (0.135) (0.591) (0.092) (0.88) After election 16.74** 16.2** 9.36 9.47 0.35 0.4 interactions F-­‐test [0.01] [0.013] [0.154] [0.149] [0.91] [0.881] Pseudo R-­‐squared 0.033 0.067 0.038 0.092 0.000 0.02 N 2527 2513 2534 2452 2534 2534 Notes: Coefficients of Probit models (for response rate and incentive offered) and OLS regression (for logged dollars). Robust standard errors in parentheses clustered at the individual level. The “Quarter” variables are combined to avoid biased standard errors; they appear here as 1st and 2nd Half (where 2nd Half is the omitted variable). Region 4 (West) is the omitted category for the region dummies. P-­‐values for joint significance are shown in brackets under the F-­‐statistics. Significance Level: *p < 0.1, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01 43