Does the law and finance hypothesis pass the test of... Aldo Musacchio * and John D. Turner

advertisement

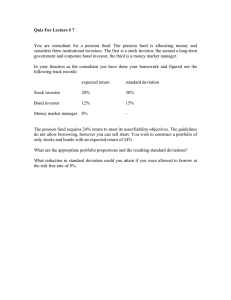

Business History Vol. 00, No. 0, 2012, 1–19 Does the law and finance hypothesis pass the test of history? Aldo Musacchioa* and John D. Turnerb a Harvard Business School, Boston, USA; bQueen’s University Management School and Queen’s University Centre for Economic History, Belfast, UK For the body of work known as the law and finance literature, the development of financial markets and the concentration of ownership across countries is to a large extent the consequence of the legal system nations created or inherited decades or hundreds of years ago. Despite the seemingly historical nature of this explanation, most of the body of work supporting the law and finance hypothesis has been ahistorical. This paper summarises the business history literature and provides evidence on investor protection and financial development over the long run that challenges the main tenets of the law and finance literature. Keywords: finance; legal origin; common law; civil law; history 1. Introduction In the 1990s, a group of US-based economists published several influential papers exploring the relationship between law (in the form of investor protection) and financial development. As financial development could affect law just as easily as law could affect financial development, these economists searched back in time for a variable that would allow them to test the direction of causation. The variable they used in their analysis was legal family or legal origin (i.e. French civil law, German civil law, Scandinavian civil law and common law). Thus, the law and finance hypothesis was born. This hypothesis can be summarised as follows. Early in their history, England, France and Germany had developed different legal styles of controlling business due to their unique histories; these styles of control were transplanted by these colonial powers and copied by independent nations rather than starting from scratch, and these styles have proved to be hysteretic as they determine economic outcomes such as financial development in the present.1 Because these legal systems were created or adopted before the development of modern financial markets, the causal story (going from legal origin to financial development) is easy to defend. Although many economists and lawyers have challenged the premises and findings of the law and finance hypothesis, much of the debate, with some notable exceptions discussed in this paper, has been ahistorical. This is somewhat puzzling given the explicit historical nature of the legal-origins hypothesis, which argues that history matters.2 It is *Corresponding author. Email: amusacchio@hbs.edu ISSN 0007-6791 print/ISSN 1743-7938 online q 2012 Taylor & Francis http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.741976 http://www.tandfonline.com 2 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner also puzzling given that history presents the greatest challenge to the law and finance hypothesis. The main proponents of the law and finance hypothesis, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-de-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer and Robert Vishny, have been so widely cited that Research Papers in Economics ranks them as the 27th, 19th, 1st and 5th (respectively) most cited economists in the world as of July 2012. According to Google Scholar, their seminal 1998 paper on the subject has been cited by 10,891 works as at July 2012.3 As their work has substantial normative implications, it has had an enormous effect on securities law and pro-market regulatory reform, particularly through the vehicle of the World Bank’s Doing Business reports.4 This influence has not always been appreciated, particularly in France and other French civil law economies.5 As recently suggested by Morck and Yeung, business history, given its methodological approach and global perspective, can make a valuable contribution to debates about causation in economics.6 Business historians can look at the broad sweep of history within different economies and observe and delineate the effect of legal changes and legal origins on financial development and vice versa. In addition, business history provides a helpful laboratory where we can look at the development of finance before the era of pervasive government regulation of financial markets and institutions as well as observing what happens whenever legal changes are introduced for the first time. The aim of this paper and this special issue of Business History is to outline the contributions business history has made and potentially can make to the law and finance debate. Our main contribution in this paper is to present a range of evidence from business history which seriously undermines important tenets of the law and finance hypothesis. This paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the law and finance debate as well as discussing some of the weaknesses with the law and finance hypothesis. The third section of the paper analyses and discusses the contribution business history can and has made to this debate as well as outlining the contribution of the papers in this special issue to the debate. The final section summarises the main findings as well as suggesting further avenues for investigation. 2. An overview of the law and finance debate Corporate governance is concerned with how suppliers of finance (i.e. shareholders and creditors) control managers and ensure that they get a return on their investment. According to Shleifer and Vishny, law and the quality of its enforcement are important determinants of what rights finance providers have and how well these rights are protected.7 Consequently, legal protection of suppliers of finance is a major determinant of the willingness of investors to finance firms.8 Ultimately, the protection of investors is a major factor in financial development.9 The above hypothesis in and of itself is uncontroversial. However, a group of USbased economists, whom we refer to as the law and finance school, in a series of papers developed the contentious hypothesis that an economy’s legal origin determines the strength of its investor protection laws and hence its financial development.10 In addition, these economists argue that corporate ownership and governance and corporate financial policy are also determined by a country’s legal origin.11 Legal origin refers to the broad legal traditions or families that countries adopted as the basis of their commercial laws either freely or by force. The two broad legal families are common law and civil law. Common law, which dates from after the Norman invasion of England and is mainly found in former British colonies, is formed by judges resolving specific disputes, with the Business History 3 judicial rulings and precedents arising from such cases shaping the common law.12 Civil law, which has its basis in Roman law and is the most widely distributed legal family, is created by jurists and legal scholars, and is codified. The most famous examples of civil codes are the French Commercial Code of 1807 and the German Civil Code of 1897. The French Code was introduced into several countries in Europe following Napoleon’s conquests and was imitated by Spain and Portugal, which resulted in the spread of French civil law to Central and South America. During the colonial era, French civil law was transplanted into the Near East, Oceania and Africa. The German legal family influenced some neighbouring European nations as well as Japan, Korea and China. Scandinavia had its own civil law tradition, but it was not transplanted into other economies. In the commercial sphere, civil law is viewed as inferior to common law as it is constructed by legal philosophers rather than emerging from the process of resolving specific business disputes. This, of course, means that civil law is potentially subject to greater political interference. In addition, the infrequent revisions of civil law codes means that they quickly become outdated, whereas the common law is inherently dynamic and pragmatic in responding to a new business environment and new business practices. For the law and finance school, ‘common law stands for the strategy of social control that seeks to support private market outcomes, whereas civil law seeks to replace such outcomes with state-desired outcomes’.13 According to the law and finance school, legal origins are largely exogenous as they were transplanted through conquest and colonisation. They therefore use legal origins as a way to overcome the identification problem associated with testing the hypothesis that investor protection laws strongly predict corporate ownership and control as well as financial development. Notably, other studies have shown that legal origin affects more than finance – e.g. legal origin is found to predict state ownership of banks, labour market regulation, military conscription, severity of currency and real crises, and government ownership of media.14 In its empirical work, the law and finance school constructs investor protection indices which attempt to measure how well an economy’s legal system protects minority shareholders and creditors from opportunistic directors. The chief leximetrics of the law and finance school are the anti-director-rights index, anti-self-dealing index and creditor rights index; the headline finding is that investor protection, as measured by these indexes, is higher in common law countries.15 A theoretical agency-based model by Shleifer and Wolfenzon implies that investor protection shapes corporate finance and the empirical evidence of the law and finance school supports this model.16 Firstly, common law and better investor protection are both associated with better developed stock markets and financial development.17 Secondly, common law and better investor protection are closely linked with diffuse ownership, whereas the civil law is associated with concentrated ownership.18 This relationship may arise because in an environment where there is poor legal protection of outside shareholders, concentrated owners may be better able to monitor managers and minority shareholders would only be willing to purchase shares at a deep discount. Thirdly, common law and better investor protection are both associated with higher dividend payouts.19 Again, this is consistent with agency theory as strong investor protection constrains managerial expropriation and empowers minority shareholders to extract dividends. Fourthly, common law and better investor protection are both connected to higher valuation of corporate assets, which is consistent with the idea that law constrains minority shareholder expropriation.20 Fifthly, poor investor protection is negatively correlated with the efficiency of capital 4 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner allocation.21 Sixthly, common law and better investor protection are both associated with better corporate investment returns.22 The law and finance school has generated much criticism from economists and legal scholars. One of the main criticisms is that the prevalence of statutory law, particularly in the financial realm, in modern-day common law countries would appear to undermine the concept and importance of judge-made law.23 However, the law and finance school responds that statutes reflect jurisprudence and the common law way of doing things and statutes often require judges to interpret and apply them as well as complex contracts.24 Another major criticism focuses on the coding, classification and empirical strategy of the law and finance school.25 For example, the coding of many Latin American economies as French civil law is a gross oversimplification.26 Comparative legal academics question whether legal origin is exogenous and static.27 Spamann using primary legal sources carefully recodes the anti-director-rights index of La Porta et al. and finds that none of their key findings hold using his more accurate index.28 A longitudinal shareholder protection index covering UK, USA, Germany, France and India for 1970–2005, which has been judiciously coded by comparative lawyers and economists, does not support the law and finance hypothesis.29 Using the La Porta et al. investor protection data, but making small changes to definitions and using different statistical techniques, Graff finds that common law is not better than civil.30 Another set of criticisms revolves around the suggestion that the legal origin may be acting as a proxy for some other variable which has been omitted from the analysis of the law and finance school. One possibility is that culture is a proxy for legal origins.31 For example, Stulz and Williamson find that civil law is usually found in societies where the dominant religion is hierarchical (e.g. Roman Catholicism) and common law is found in societies which stress individualistic religion (e.g. Protestantism). A further possibility is that legal origin is a proxy for a society’s historical decision about the role of the state and protecting property from expropriation by the state.32 In other words, societies which desired limited government and secure property rights selected a common law legal system. Another possibility is that legal origin could be a proxy for the way in which law was transplanted and received in a country.33 An additional possibility is that legal origin could be proxying for initial colonisation conditions.34 Yet another possibility is that legal origin is a proxy for a country’s political instability or its electoral system.35 3. Law, finance and business history History plays a central role in the legal-origin hypothesis as the hard-wiring of the legal system in the past determines the present state of investor protection and financial markets. But why did differences emerge between English common law and French (and to a lesser extent German) civil law? One explanation focuses on the Glorious Revolution in England and the French Revolution.36 In the case of the former, lawyers were on the winning side and, as a result, English law developed judicial independence, respect for private property and freedom of contract. In the case of the latter, lawyers were on the losing side and, as a result, there was no judicial independence in French law and the government administration was expanded to cope with social problems. Another explanation suggests that the differences did not emerge in the early modern period, but in the medieval era.37 England was relatively peaceful in this era whereas France faced internal and external threats. Consequently, dispute resolution in England was decentralised to independent juries, whereas in France, state-employed judges resolved disputes. However, as freely admitted by the law and finance school, history perhaps provides the greatest challenge to the legal-origin hypothesis.38 Business history challenges the law Business History 5 and finance school in at least four ways which we discuss below and which are addressed in this special issue of Business History. 3.1 Corporate ownership and legal origins The law and finance school argues that common law results in better legal protection for minority shareholders, which, in turn, facilitates a separation of ownership from control. Holderness has recently questioned the contemporary empirical basis for this hypothesis by providing evidence that ownership concentration in the US is similar to that of many civil law economies.39 However, business history provides two more substantial problems for the legal-origin view of ownership: (a) ownership dispersion occurred before the strengthening of shareholder protections in some countries, and (b) the separation of ownership and control in corporations was commonplace in some economies in the nineteenth century.40 The law and finance literature, for instance, influenced by the work of Berle and Means, assumes that ownership separated from control in the United States in the early part of the twentieth century and they envision it staying like that for decades. Yet Hilt finds that ownership was separated from control in early nineteenth-century US corporations despite the fact that corporate law offered few protections to shareholders.41 Furthermore, Lipartito and Morii use ownership data for the largest American corporations in the 1930s and find less separation between ownership and control, and more ownership concentration, than Berle and Means found in their 1932 book.42 In other countries, business historians have had similar findings challenging the historical ‘stability’ or monotonic trends assumed by the law and finance literature. Franks et al. find that corporate ownership in Japan was dispersed in the first half of the twentieth century and that the move to concentrated ownership in Japan coincided with a marked strengthening of investor protection law.43 In the case of Brazil before 1910, Musacchio finds that ownership concentration was relatively low compared to the modern period, which implies the modern-day concentration of ownership in Brazil is due more to its twentieth-century history rather than its civil law legal origin.44 One of the prime counterexamples to the law and finance hypothesis is the case of Germany prior to 1913. Recent evidence indicates that Germany, despite having a civil law system, had a very well-developed stock market before 1913 relative to the modern era and a trend towards diffuse ownership.45 In the case of the UK, Coffee, Cheffins, and Franks et al. argue that the separation of ownership from control, which by their reckoning occurred sometime between the 1930s and 1970s, preceded the strengthening of investor protection law.46 La Porta et al. have responded to this criticism by suggesting that new legislation passed at the turn of the twentieth century, as well as having the best commercial courts in the world, meant that shareholders in the UK were well protected, with the result that the rise of diffuse ownership in the twentieth century is unsurprising.47 However, the UK puzzle still persists because recent research has convincingly argued that diffuse ownership was commonplace by the first decade of the twentieth century,48 and this separation occurred in a laissez-faire environment with regard to shareholder protection.49 Firstly, little protection was afforded by legislative law or by the rules of the organised security markets.50 Secondly, and in complete contradiction to the above claims of La Porta et al., common law judges in Victorian Britain were averse to interfering in the internal business affairs of companies in order to protect the interests of outside shareholders apart from cases of outright fraud.51 If anything, the judiciary was ideologically hostile towards the concept of protecting outside shareholders, as demonstrated in the precedent set by Foss v. Harbottle,52 because laissez-faire theory and the practice of partnerships taught that capitalists could look after themselves.53 6 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner In this special issue, Cheffins, Koustas and Chambers contribute further to the debate regarding corporate ownership in early twentieth-century Britain by examining whether or not law, in the form of the listing rules of the London Stock Exchange, contributed to the separation of ownership from control. Consistent with the extant literature, they find that law does not contribute to the emergence of diffuse ownership. British companies as well as the wider economy may have seriously underperformed as a result of this corporate ownership structure, with severe agency problems and directors expropriating shareholders. However, two papers in this special issue suggest that this was not the case. First, Braggion and Moore find that despite the profitability of insider trading and the absence of laws against such practices, insider trading in this era was very moderate. Second, Foreman-Peck and Hannah find that the separation of ownership from control in Edwardian Britain did not harm shareholders. Although the UK evidence does not appear to support the hypothesis that legal origins do not determine corporate ownership and governance, the UK experience is consistent with Coffee, who suggests that dispersed ownership arose not because of specific legal rules per se, but because of the emergence of a decentralised and pluralistic political regime, which resulted in a private sector relatively free from government interference and which permitted entrepreneurs to use private contracts to make credible commitments to small shareholders.54 This is also consistent with Acemoglu and Johnson who argue that property rights institutions as described by Coffee are more important for economic and financial development than contracting institutions such as legal protection of investors.55 The question ultimately arises as to how investors protected themselves or how entrepreneurs made credible commitments to not expropriate minority shareholders in these laissez-faire regulatory environments where ownership was separated from control. One possibility is that early corporations constrained the power of insiders vis-à-vis minority shareholders by using graduated and capped voting scales instead of one-share-one-vote rules.56 In a sense, these rules had an investor protection rationale. Parglender and Hansmann in their paper in this special issue argue that this was not the primary rationale for these voting schemes. They suggest a consumer protection rationale for these rules as most shareholders in early corporations were also customers, and graduated voting rules prevented corporations abusing their monopoly power. Hilt takes issue with this view in his paper in this special issue: his archival evidence of New York corporations in the early nineteenth century supports the investor protection rather the consumer protection rationale. In the case of the UK in the Victorian era, recent evidence suggests that graduated voting schemes did not perform an investor protection role; they appear to have been a hangover from an earlier era.57 Evidence from the Victorian and Edwardian eras suggests that corporate governance structures which were contained in firm’s founding constitutions provided investors with protection.58 Dividend policy and capital-market pressure may also have acted as a substitute for investor protection at this time.59 Trust and proximity of investors to directors may also have been important in this market.60 3.2 Financial development and law in the long run If the law and finance hypothesis is correct, common law countries should have been more financially developed and had higher investor protection in the past than their civil law counterparts. A further implication of the legal-origin hypothesis is that investor protection laws and financial development should be correlated over time. Bordo and Rousseau find a relationship between legal origin and financial development in the past.61 However, their measure of financial development is the ratio of broad money to Business History 7 GDP, which is more a measure of banking development rather than financial market development. Rajan and Zingales, using more appropriate measures of financial market development, challenge the legal-origin school by highlighting the great reversal puzzle: financial markets prior to 1913 were more developed in civil law countries than their common law counterparts, but after 1913, financial markets in civil law countries declined and were overtaken by common law countries.62 However, the data used by Rajan and Zingales have been criticised for overestimating stock market capitalisation for several civil law regimes, whilst underestimating it for some common law countries.63 Musacchio, using new estimates of financial development in 1900 and 1913, finds little evidence to support the view that there were substantial differences across legal origins at the turn of the twentieth century.64 According to Table 1, which contains six measures of financial development for 24 economies in 1913, civil law countries in 1913 may have been more financially developed than their common law counterparts according to five of the six financial development metrics we include in this table. In terms of the sixth metric, stock market capitalisation/GDP, the common law average is a lot higher than the French civil law average, but below the German civil law average and just above the Scandinavian civil law average. Overall, the main implication of Table 1 is that the financial systems of common law countries were not more developed in 1913 than those of civil law countries, which should not be the case if the law and finance hypothesis holds. In Table 2, we compare shareholder rights across several economies in c.1910, 1997 and 2005 using the anti-director rights index (ADRI), which measures how well minority shareholders are protected vis-à-vis directors. Three things are worthy of note. First, there was not much difference between legal regimes in c.1910, which is contrary to the law and finance hypothesis. Second, shareholder protection improved in the twentieth century in all legal regimes. Third, Spamann’s recoding of the anti-director rights index (see above) means that that the common law no longer provides higher shareholder protection than its civil law counterparts at the end of the twentieth century. From Table 3, which compares creditor rights across 13 countries in c.1910 and 1995, we can see that creditor rights were similar across legal regimes in c.1910. Similarly, Sgard’s study of bankruptcy law across European economies suggests that all legal traditions provided strong creditor protection over the period 1808 –1914, but that English common law provided less protection than its continental counterparts.65 Notably, we also see from Table 3 that creditor rights have been weakened in these 13 economies during the twentieth century, particularly in civil law countries. The fact that there are few differences in shareholder and creditor protection across legal systems in c.1910 suggests that if legal origin does affect financial development it is not through the channel of investor protection laws. Furthermore, the changes in investor protection laws over the twentieth century do not appear to be correlated with legal origin. Indeed, one of the puzzles for business historians which emerges from the above analysis is why creditor protection laws appear to have weakened in many countries over the twentieth century, whereas shareholder protection laws have been strengthened. There is also an emerging literature which examines the time-series variation of investor protection laws and financial development. For example, in the case of Brazil, a civil law country, there is a lot of time variation in creditor rights and corporate bond market size from the late nineteenth century up to the present day.66 In addition, contrary to the law and finance hypothesis, there is no evidence to suggest that Brazilian bond market development is correlated with creditor rights. In Table 4, we examine the evolution of shareholder and creditor protection laws and the development of the UK’s stock and bond markets over the course of the twentieth 0.39 0.74 0.02 0.22 0.98 0.95 0.55 0.76 0.44 0.49 1.23 0.73 0.17 0.99 0.20 0.17 0.33 0.44 0.54 0.17 0.56 0.31 0.16 0.37 Australia Canada India South Africa United Kingdom United States Common law average Austria Germany Japan Switzerland German civil law average Argentina Belgium Brazil Chile Cuba Egypt France Italy Netherlands Spain Uruguay French civil law average Stock market capitalisation/GDP – 0.23 – – – – 0.14 0.07 0.38 0.01 – 0.17 – 0.07 0.08 0.03 0.06 – – – – 0.14 0.04 0.07 Fraction of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity Table 1. Financial development around the world, 1913. 0.01 0.25 0.15 – – 0.06 0.38 0.05 – 0.31 0.01 0.15 0.20 0.07 0.02 0.18 0.12 0.01 0.10 – 0.04 0.19 0.37 0.14 Stock of corporate bonds/GDP 0.37 1.00 0.38 – – – 1.50 0.48 – – 0.71 0.74 – 1.66 0.58 0.88 1.04 – 0.42 – 0.40 1.07 0.96 0.71 Private credit/GDP 15.29 108.70 12.43 20.62 12.69 16.58 13.29 6.32 65.87 – 15.60 28.74 38.72 27.96 7.53 61.53 33.94 61.74 14.65 0.82 – 47.06 4.75 25.80 Listed companies per million people 0.29 0.68 0.12 0.16 – – 0.42 0.23 0.22 0.07 – 0.27 1.12 0.53 0.13 0.93 0.68 0.37 0.22 0.04 0.09 0.10 0.33 0.19 Deposits/ GDP 8 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner 0.86 0.16 0.47 0.51 Stock market capitalisation/GDP – – 0.08 0.08 Fraction of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity 0.03 0.06 – 0.06 Stock of corporate bonds/GDP 2.23 1.12 – 1.67 Private credit/GDP 38.22 33.51 20.64 30.79 Listed companies per million people 0.76 0.65 0.69 0.70 Deposits/ GDP Sources: Stock market capitalisation/GDP, private credit/GDP, and stock of corporate bonds/GDP are from Musacchio, “Law and Finance,” 58. The United Kingdom’s stock of corporate bonds/GDP is from Coyle and Turner, “Law” and the UK’s stock market capitalisation/GDP for 1913 is based on Musacchio, “Law and Finance” and Coyle and Turner, “Law.” Proportion of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity, listed companies per million people, and deposits/GDP are from Rajan and Zingales, “Great Reversals,” 14–17. The listed companies per million people for Uruguay for 1913 Musacchio, “Law and Finance,” 58. Denmark Norway Sweden Scandinavian civil law average Table 1 – continued Business History 9 10 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner Table 2. Shareholder rights across countries, c.1910, 1997 and 2005. ADRI, LLSV’s original Spamann’s Corrected c.1910 ADRI, 1997 ADRI, 1997 Spamann’s Corrected ADRI, 2005 Common law United Kingdom United States 2 3/4 5 5 4 2 5 2 German civil law Germany Japan 1 2 1 4 4 5 4 5 French civil law Italy France Brazil Chile Egypt 1 2 2 0 2 1 3 3 5 2 2 5 5 5 4 4 5 5 5 4 Scandinavian civil law Sweden 2 3 4 4 Sources: The ADRI for UK in 1910 is from Cheffins, Corporate Ownership, 36. The ADRI for the US in 1910 is for the state of Delaware and is from the Cheffins, Banks and Wells paper in this special issue. All the other ADRI scores for c.1910 are from Musacchio, “Law and Finance,” 68. LLSV original ADRI scores are from La Porta et al., “Law and Finance,” Table 2. Spamann’s corrected ADRI for 1997 and 2005 are from Spamann, “Antidirector Rights Index,” Table 1. Notes: ADRI is the Anti-Director Rights Index, which measures the power of minority shareholder vis-à-vis directors. It has the following six components: (i) proxy voting by mail allowed; (ii) shares not blocked before shareholder meetings; (iii) cumulative voting/proportional representation; (iv) provision for minority shareholders to challenge directors; (v) shareholders have a pre-emptive right to new issues; (vi) capital required to call an extraordinary general meeting is less than or equal to 10%. If present, each component contributes a one to the ADRI, which means the maximum ADRI is six. A score of six implies that minority shareholders are well protected. century. It is clear that the time-series variation in the size of the UK bond market cannot be explained by changes in creditor protection scores, which stay constant throughout the century.67 Similarly, there does not appear to be much correlation between shareholder protection and the development of the stock market. For example, the anti-director rights index and the ex post private control of self-dealing index both increased after World War II, but, as can be seen from Table 4, the ratio of stock market capitalisation to GDP as well as the fraction of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity declined. Building on these previous studies which look at the time-series variation of investor protection laws and financial development, Cheffins, Bank and Wells in their paper in this special issue look at the development of investor protection law and the stock market in the US over the period 1930 – 70. They find that, contrary to what the law and finance hypothesis would predict, US corporate law did not provide extensive protection to shareholders in this era. In addition, they highlight that while federal securities law increased investor protection, this did not result in stock market development. 3.3 Law and finance during industrialisation If legal origin matters today, it should also have mattered during the first and second eras of industrialisation. Lamoreaux and Rosenthal suggest that the supposed inflexible civil law of France offered businesspeople a greater menu of organisational choice during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries than the common law of the US.68 The Business History 11 Table 3. Creditor rights across countries, c.1910 and 1995. Creditor rights index, c.1910 Creditor rights index, 1995 Common law United Kingdom United States Canada Australia Hong Kong India Singapore Mean of common law 4 2 4 4 2 3 2 3.0 4 1 1 1 4 4 4 2.7 French civil law France Belgium Spain Argentina Uruguay Brazil Mean of French civil law 3 3 3 3 3 3 3.0 0 2 2 1 2 1 1.3 Sources: Creditor rights for c.1910 are from Musacchio, “Can Civil Law,” 99 and Musacchio, “Law and Finance,” 67. Creditor rights for 1995 are from La Porta et al., “Law and Finance,” Table 4. Notes: The four components of the creditor rights index are as follows: (a) no automatic stay on assets; (b) secured creditors have first priority; (c) creditors approve reorganisation; (d) management does not stay during reorganisation. Each component scores a one if it is present, with the result that the maximum score for the creditor rights index is four. Table 4. The twentieth-century evolution of legal protection and financial development in the United Kingdom. Anti-director rights index Ex post private control of self-dealing Creditor protection index Stock market capitalisation/GDP Stock of traded corporate bonds/GDP Fraction of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity 1900 1913 1938 1950 1970 1999 2.00 0.14 4.00 1.06 0.19 – 2.00 0.14 4.00 0.98 0.19 0.14 2.00 0.14 4.00 1.14 0.12 0.09 3.00 0.14 4.00 0.33 0.061 0.08 3.00 0.64 4.00 0.66 0.032 0.01 5.00 0.64 4.00 1.52 0.01 0.12 Sources: Anti-director rights index and ex post private control of self-dealing index are from Cheffins, Corporate Ownership, 36–8. Creditor protection index is from Coyle and Turner, “Law.” Stock market capitalisation/GDP for 1900 and 1913 are based on Musacchio, “Law and Finance” and Coyle and Turner, “Law.” The stock market capitalisation/GDP figures for 1938, 1950, 1970 and 1999 are from Rajan and Zingales, “Great Reversals,” 15. Stock of corporate bonds/GDP figures are from Coyle and Turner, “Law.” Proportion of gross fixed-capital formation raised via equity is from Rajan and Zingales, “Great Reversals,” 16. Notes: 11946 figure; 21969 figure. Anti-Director Rights Index, which measures the power of minority shareholder vis –à –vis directors. It has the following six components: (i) proxy voting by mail allowed; (ii) shares not blocked before shareholder meetings; (iii) cumulative voting/proportional representation; (iv) provision for minority shareholders to challenge directors; (v) shareholders have a pre-emptive right to new issues; (vi) capital need to call an extraordinary general meeting is less than or equal to 10%. If present, each component contributes a one to the index, which means the maximum is six. A score of six implies that minority shareholders are well protected. The ex post private control of self-dealing averages scores which measure the constraints on a corporate insider engaging in self-dealing – the maximum score is one (see Djankov et al., “Law and Economics” for the details). 12 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner French civil law was also better able to adapt to new business and economic needs than the common law of the US, and in the US new statutes were required to introduce new business organisational forms. Similarly, a study of the menu of organisational choices in Germany, France, the UK and the US reveals that, if anything, the menu of organisational choices offered to entrepreneurs by the legal systems of the two common law countries in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries was inferior to that of the two civil law countries.69 Likewise, in the case of late nineteenth-century Mexico, which had a civil law regime, it appears that there was also a wider variety of organisational choice than in common law countries, but this wider menu appears to have had a negligible effect on capital formation.70 Overall, this evidence questions the supposition made by the legal-origin school that common law is a lot more flexible and business-friendly than civil law. A flaw with much of the law and finance research agenda is that it compares the political sensitivity of judicial systems because modern legal systems are predominantly based on statutory law. Therefore, a comparison of the Scottish civil law system with the English common law system during the first era of industrialisation makes for an interesting study as it predates the Benthamite-inspired statutory intervention in business law. Thus, we have a relatively pure contrast of the efficacy of these two legal origins. Acheson et al. find that the Scottish system gave entrepreneurs wishing to establish banks a greater organisational flexibility during the Industrial Revolution.71 Unlike their English counterparts under the common law, Scottish partnership law allowed banks to separate ownership from control in that only designated officers of the bank, and not every owner, could enter binding contracts on behalf of the bank. In addition, shares in Scottish banks were transferable, whereas English partnership law meant dissolution of the bank if one of the partners wanted to exit. This difference appears to have had real economic consequences as the Scottish banking system was more stable than England’s during this era. Freeman et al. in their contribution to this special issue also compare Scotland with England. They argue that, in the case of England, statute law had a greater impact than the common law on the development of corporate governance, whereas in Scotland, judicial rulings rather than statutes were more important. They also find that law influenced corporate governance practices less than the law and finance school predicts, with practices converging after 1825. This, of course, is the opposite of what the legal-origin school argues. The legal systems of both England and Scotland appear to have been reluctant to promote joint-stock enterprises at the expense of the partnership organisational form.72 Indeed, the English common law during the Industrial Revolution was so conservative that the resulting legal stasis hindered the rise of the joint-stock corporation.73 Ultimately, it required parliamentary intervention via statutes to facilitate the development of the jointstock corporation in the nineteenth century.74 The role of the legislature in promoting incorporation activity was not unique to Britain. Hilt’s paper in this special issue stresses that the legislatures in the US engaged in legal innovation which stimulated the establishment of corporations in order to promote economic development. Ultimately, according to Sylla and Wright’s contribution to this special issue, what mattered for the development of US corporations was not legal tradition, laws or politics, but the development of a superior form of government ushered in by the Constitution. Business History 13 3.4 Legal origin, politics and history A significant challenge to the legal-origin school is that investor protection is endogenous to the prevailing views of the political majority. One strand of this political-economy view of financial development essentially argues that a country’s experience of military invasion, war and occupation during the twentieth century resulted in differences in politics and political ideologies, which in turn resulted in different policies towards finance and stock markets.75 Civil law countries experienced greater devastation than common law countries as a result of the major conflicts of the twentieth century (particularly World War II), and this difference explains the findings of the legal-origin school. Similarly, Roe and Roe and Siegel suggest that to understand the disparity in current financial development, we need to comprehend the effect of the cataclysmic events of the twentieth century on financial markets.76 Additional support for the political-economy view of financial development comes from ancient Rome. Ancient Rome is important to the law and finance debate because civil law has its origins in Roman law, which was documented for posterity by Justinian in the Corpus Iuris Civilis. Notwithstanding this, Roman law has had considerable influence and continues to have influence on the development of English common law, which raises concerns about the sharp dichotomy between civil and common law which is at the heart of the law and finance hypothesis.77 In addition, Roman law was case law, which made Roman law highly flexible and enabled it to adapt to the transformation of Rome from a rural backwater to a sprawling empire.78 A closer look at Roman law and the societas publicanorum, a form of proto-company in ancient Rome, reveals that this institutional form flourished in a legally primitive but politically supportive era of the Roman Republic, but disappeared when Rome became legally sophisticated and when its political support disappeared.79 This is consistent with the view that law matters little for economic development and that law merely reflects the interests of the political classes. 4. Conclusions Business history suggests that legal origins do not matter – they are not deterministic. On the other hand, business history suggests that contingent factors such as conflict, political upheaval, inflation and economic disorder play a larger role in driving financial development. There is thus a new synthesis emerging when it comes to studying corporate finance and governance in the past. Laws were important, but legal origins did not determine significant differences across countries. In fact, differences across countries were not as cross-cutting as today. The role of law in the past was simply to uphold and enforce private contracts. As entrepreneurs, businesspeople and investors were aware of governance problems and the potential for opportunistic behaviour, they contracted privately to ameliorate these problems. This implies that rather than waiting for reforms of the whole legal system of a country or set of countries, business history teaches us that companies need to do their part. Following on from this special issue, business history can contribute further to the law and finance debate in at least four ways. First, we need to know a lot more about the early development of stock markets and corporate ownership in civil law economies of Europe, Latin America and Asia. Second, we need case studies on how changes in investor protection laws occurred across time and space – who championed or lobbied for changes to investor protection law? Third, we need to know more about how legal families and laws governing business enterprises were transplanted into colonies and how colonies 14 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner received legal families and adapted mother-country commercial laws. Fourth, we need to know more about doing business in the past and, in particular, how businesspeople across the globe structured contracts with investors. Consequently, there needs to be much more archival work looking at company by-laws and constitutions. Our hope is that the essays included in this special volume will energise the debate and inspire business historians to work on the history of corporate governance, investor protections, financial regulation, and financial development. Acknowledgements This paper serves as the introduction of the special issue of Business History entitled ‘Law and Finance: A Business History Perspective’. Thanks to Steve Toms and John Wilson, the journal’s editors for all their assistance. Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. La Porta et al., “Economic Consequences,” 306– 7. See Xu, “Role of Law” for a recent survey. The legal-origin hypothesis is part of a growing literature in economics which stresses the importance of the effect of historic events on long-term economic development (Engerman and Sokoloff, “Factor Endowments”; Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson, “Colonial Origins,” “Reversal of Fortune”). See Nunn, “Importance” for a recent survey. La Porta et al., “Law and Finance.” Michaels, “Comparative Law.” Fauvarque-Cosson and Kerhuel, “Is Law an Economic Contest?” Morck and Yeung, “Economics, History, and Causation.” Shleifer and Vishny, “Survey of Corporate Governance.” La Porta et al., “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation.” La Porta et al., “Legal Determinants,” “Law and Finance,” “Economic Consequences”; Djankov et al., “Debt Enforcement,” “Law and Economics”; Levine, “Legal Environment,” “Law”; Levine, Loayza and Beck, “Financial Intermediation.” La Porta et al., “Legal Determinants,” “Law and Finance.” La Porta et al., “Investor Protection and Corporate Governance,” “Corporate Ownership,” “Agency Problems.” See Dam, “Legal Institutions,” for an overview of the common and civil legal traditions. La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Economic Consequences,” 286. Botero et al., “Regulation of Labor”; Djankov et al., “Who Owns the Media?”; Du, “Institutional Quality”; Mulligan and Shleifer, “Conscription”; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Government Ownership.” The details of these leximetrics can be found in La Porta et al., “Law and Finance”; Djankov et al., “Law and Economics,” “Private Credit.” Shleifer and Wolfenzon, “Investor Protection.” La Porta et al., “Legal Determinants.” La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Corporate Ownership.” La Porta et al., “Agency Problems.” La Porta et al., “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation.” See also Claessens et al., “Disentangling.” Wurgler, “Financial Markets.” Gugler, Mueller and Yurtoglu, “Corporate Governance.” Dam, “Legal Institutions.” La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Economic Consequences,” 290– 91. See Armour et al., “Shareholder Protection,” for a good summary. Dam, “Legal Institutions.” Pistor, “Rethinking”; Michaels, “Comparative Law.” Spamann, “Antidirector Rights Index.” Armour et al., “Shareholder Protection,” “How Do Legal Rules Evolve?,” “Law and Financial Development”; Sarkar and Singh, “Law.” Business History 30. 31. 32. 33. 34. 35. 36. 37. 38. 39. 40. 41. 42. 43. 44. 45. 46. 47. 48. 49. 50. 51. 52. 53. 54. 55. 56. 57. 58. 59. 60. 61. 62. 63. 64. 65. 66. 67. 68. 69. 70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. 77. 78. 15 Graff, “Law and Finance.” Licht, Goldschmidt and Schwartz, “Culture”; Stulz and Williamson, “Culture.” Mahoney, “Common Law”; Klerman and Mahoney, “Legal Origin.” Berkowitz, Pistor and Richard, “Economic Development.” Acemoglu and Johnson, “Unbundling Institutions.” Pagano and Volpin, “Political Economy”; Roe and Siegel, “Political Instability.” Merryman, Civil Law; Klerman and Mahoney, “Legal Origin.” Glaesar and Shleifer, “Legal Origins.” Curran, “Comparative Law,” 863; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Economic Consequences,” 315. Holderness, “Myth of Diffuse Ownership.” See Morck and Steier, “Global History,” 38 Hilt, “When Did Ownership.” Lipartito and Morii, “Rethinking the Separation”; Berle and Means, The Modern Corporation. Franks, Meyer and Miyajima, “Equity Markets.” Musacchio, Experiments, 126; Musacchio, “Laws Versus Contracts.” See Fohlin, “History,” 227; Fohlin, “Does Civil Law,” Finance Capitalism. Cheffins, “History,” “Does Law Matter?,” Corporate Ownership; Coffee, “Rise of Dispersed Ownership”; Franks, Mayer and Rossi, “Ownership.” La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Economic Consequences,” 319. Hannah, “Divorce of Ownership”; Foreman-Peck and Hannah, “Extreme Divorce”. Braggion and Moore, “Dividend Policies,” also find something similar for a small sample of companies at the turn of the twentieth century. Campbell and Turner, “Substitutes.” Ibid., 574 –5. See Emden, Shareholders’ Legal Guide, 77 – 80. Foss v. Harbottle (1843) 2 Hare 461 (Chancery Division) Wigram V-C. Jefferys, Business Organisation, 394. Coffee, “Rise of Dispersed Ownership.” Acemoglu and Johnson, “Unbundling Institutions.” Hilt, “When Did Ownership”; Musacchio, Experiments. See also Dunlavy, “Social Conceptions,” who argues that voting rights of early corporations reflected social and political conceptions of democracy. Campbell and Turner, “Substitutes.” Ibid. See also the Foreman-Peck and Hannah paper in this special issue. Campbell and Turner, “Substitutes”; Cheffins, “Dividends.” See Braggion and Moore in this special issue as well as Chambers and Dimson, “IPO Underpricing.” Bordo and Rousseau, “Legal – Political Factors.” Rajan and Zingales, “Great Reversals.” La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes and Shleifer, “Economic Consequences,” 316– 19; Sylla, “Schumpeter Redux.” Musacchio, “Law and Finance,” “Can Civil Law.” Sgard, “Do Legal Origins Matter?” Musacchio, “Can Civil Law.” Coyle and Turner, “Law.” Lamoreaux and Rosenthal, “Legal Regime.” Guinnane et al., “Putting the Corporation.” Gómez-Galvarriato and Musacchio, “Organizational Choice.” Acheson, Hickson and Turner, “Organizational Flexibility.” Freeman, Pearson and Taylor, “Different.” Harris, “Industrializing.” Dicey, Lectures, 245– 6. Rajan and Zingales, “Great Reversals”; Roe, “Legal Origins”; Perotii and von Thadden, “Political Economy.” Roe, “Legal Origins”; Roe and Siegel, “Political Instability.” See Malmendier, “Roman Law,” “Law and Finance.” Malmendier, “Roman Law,” 8. 16 79. A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner Malmendier, “Law and Finance.” Notes on contributors Aldo Musacchio is an associate professor at Harvard Business School and a Faculty Research Fellow at the NBER. He is the author of Experiments in Financial Democracy: Corporate Governance and Financial Development in Brazil (CUP, 2009). He has published a number of articles studying the connection between law and financial development circa 1900. John D. Turner is a professor of finance and financial history at Queen’s University Belfast and the director of the Queen’s University Centre for Economic History. He has been a Houblon-Norman Fellow at the Bank of England as well as the Alfred D. Chander Jr. Visiting Fellow at Harvard Business School. He has published numerous journal articles on law, finance and history. References Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. “The Colonial Origins of Comparative Development: An Empirical Investigation.” American Economic Review 91 (2001): 1369– 1401. Acemoglu, Daron, Simon Johnson, and James A. Robinson. “Reversal of Fortune: Geography and Institutions in the Making of the Modern World Income Distribution.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (2002): 1231– 1294. Acemoglu, Daron, and Simon Johnson. “Unbundling Institutions.” Journal of Political Economy 113 (2005): 949– 995. Acheson, Graeme G., Charles R. Hickson, and John D. Turner. “Organizational Flexibility and Governance in a Civil Law Regime: Scottish Provincial Banking during the Industrial Revolution.” Business History 53 (2011): 505– 529. Armour, John, Simon Deakin, Priya Lele, and Matthias Siems. “How Do Legal Rules Evolve? Evidence from a Cross-Country Comparison of Shareholder, Creditor, and Worker Protection.” American Journal of Comparative Law 57 (2009): 579– 629. Armour, John, Simon Deakin, Priya Lele, and Matthias Siems. “Law and Financial Development: What We Are Learning from Time-Series Evidence.” Brigham Young University Law Review (2009): 1435– 1500. Armour, John, Simon Deakin, Prabirjit Sarkar, Matthias Siems, and Ajit Singh. “Shareholder Protection and Stock Market Development: An Empirical Test of the Legal Origins Hypothesis.” Journal of Empirical Legal Studies 6 (2009): 343– 380. Berle, Adolf A., and Gardiner C. Means. The Modern Corporation and Private Property. Rev. ed. New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc., 1967 [1932]. Berkowitz, Daniel, Katharina Pistor, and Jean-Francois Richard. “Economic Development, Legality, and the Transplant Effect.” European Economic Review 47 (2003): 165– 195. Bordo, Michael D., and Peter L. Rousseau. “Legal – Political Factors and the Historical Evolution of the Finance – Growth Link.” European Review of Economic History 10 (2006): 421– 444. Botero, Juan C., Simeon Djankov, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “The Regulation of Labor.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 119 (2004): 1339– 1382. Braggion, Fabio, and Lyndon Moore. “Dividend Policies in an Unregulated Market: The London Stock Exchange 1895– 1905.” Review of Financial Studies 24 (2011): 2935– 2973. Campbell, Gareth, and John D. Turner. “Substitutes for Legal Protection: Corporate Governance and Dividends in Victorian Britain.” Economic History Review 64 (2011): 571– 597. Curren, Vivian G. “Comparative Law and the Legal Origins Thesis: ‘Non Scholae Se Vitae Discimus’.” American Journal of Comparative Law 57 (2009): 863– 876. Chambers, David, and Elroy Dimson. “IPO Underpricing Over the Very Long-Run.” Journal of Finance 64 (2009): 1407– 1443. Cheffins, Brian R. “History and the Global Corporate Governance Revolution: The UK Perspective.” Business History 42 (2001): 87 – 118. Cheffins, Brian R. “Does Law Matter? The Separation of Ownership and Control in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Legal Studies 30 (2001): 459– 484. Cheffins, Brian R. “Dividends as a Substitute for Corporate Law: The Separation of Ownership and Control.” Washington and Lee Law Review 63 (2006): 1273– 1338. Business History 17 Cheffins, Brian R. Corporate Ownership and Control: British Business Transformed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. Claessens, Stijn, Simeon Djankov, Joseph P. H. Fan, and Larry H. P. Lang. “Disentangling the Incentive and Entrenchment Effects of Large Shareholdings.” Journal of Finance 58 (2002): 2741– 2771. Coffee, John C. “The Rise of Dispersed Ownership: The Roles of Law and the State in the Separation of Ownership and Control.” The Yale Law Journal 111 (2001): 1 – 82. Coyle, Christopher, and John D. Turner. “Law, Politics and Financial Development: The Great Reversal of the UK Corporate Debt Market.” Queen’s University Belfast Working Paper (2012). Dam, Kenneth W. “Legal Institutions, Legal Origins, and Governance.” John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper (2006): 303. Dicey, A.V. Lectures on the Relation between Law and Public Opinion in England during the Nineteenth Century. London: Macmillan, 1917. Djankov, Simeon, Caralee McLeish, Tatiana Nenova, and Andrei Shleifer. “Who Owns the Media?” Journal of Law and Economics 46 (2003): 341–381. Djankov, Simeon, Caralee McLeish, and Andrei Shleifer. “Private Credit in 129 Countries.” Journal of Financial Economics 84 (2007): 299– 329. Djankov, Simeon, Rafael La Porta, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “The Law and Economics of Self-Dealing.” Journal of Financial Economics 88 (2008): 430– 465. Djankov, Simeon, Oliver Hart, Caralee McLeish, and Andrei Shleifer. “Debt Enforcement around the World.” Journal of Political Economy 116 (2008): 1105– 1149. Du, Julan. “Institutional Quality and Economic Crises: Legal Origin Theory Versus Colonial Strategy Theory.” Review of Economics and Statistics 92 (2010): 173– 179. Dunlavy, Colleen A. “Social Conceptions of the Corporation: Insights from the History of Shareholder Voting Rights.” Washington & Lee Law Review 63 (2006): 1347– 1387. Emden, Alfred. The Shareholders’ Legal Guide; Being a Statement of the Law Relating to Shares, and of the Legal Rights and Responsibilities of Shareholders. London: William Clowes and Sons, 1884. Engerman, Stanley L., and Kenneth L. Sokoloff. “Factor Endowments.” Inequality, and Paths of Development among New World Economies. NBER Working Paper 9259 (2002). Fauvarque-Cosson, Bénédicte, and Anne-Julie Kerhuel. “Is Law an Economic Contest? French Reactions to the Doing Business World Bank Reports and Economic Analysis of Law.” American Journal of Comparative Law 57 (2009): 811– 830. Fohlin, Caroline. “The History of Corporate Ownership and Control in Germany.” In A History of Corporate Governance Around the World, edited by Randall K. Morck, 223– 282. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Fohlin, Caroline. Finance Capitalism and Germany’s Rise to Industrial Power. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007. Fohlin, Caroline. “Does Civil Law Tradition and Universal Banking Crowd Out Securities Markets? Pre-World War I Germany as a Counter-Example.” Enterprise and Society 8 (2007): 602–641. Foreman-Peck, James, and Leslie Hannah. “Extreme Divorce: The Managerial Revolution in UK Companies before 1914.” Economic History Review 65 (2012): 1217– 1238. Franks, Julian, Colin Mayer, and Stefano Rossi. “Ownership: Evolution and Regulation.” Review of Financial Studies 22 (2009): 4009– 4056. Franks, Julian, Colin Mayer, and Hideaki Miyajima. “Equity Markets and Institutions: The Case of Japan.” RIETI Discussion Paper Series 09-E-039 (2009). Freeman, Mark, Robin Pearson, and James Taylor. “Different and Better? Scottish Joint-Stock Companies and the Law, c.1720– 1845.” English Historical Review 122 (2007): 61 – 81. Glaeser, Edward L., and Andrei Shleifer. “Legal Origins.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 117 (2002): 1193– 1229. Gómez-Galvarriato, Aurora, and Aldo Musacchio. “Organizational Choice in a French Civil Law Underdeveloped Economy: Partnerships, Corporations and the Chartering of Business in Mexico, 1886– 1910.” Harvard Business School Working Paper 05 – 024 (2004). Graff, Michael. “Law and Finance: Common Law and Civil Law Countries Compared – An Empirical Critique.” Economica 74 (2008): 60 – 83. Gugler, Klaus, Dennis C. Mueller, and B. Burcin Yurtoglu. “Corporate Investment and the Returns on Investment.” Journal of Law and Economics 47 (2004): 589– 633. 18 A. Musacchio and J.D. Turner Guinnane, Timothy, Ron Harris, Naomi R. Lamoreaux, and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. “Putting the Corporation in its Place.” Enterprise and Society 8 (2007): 687– 729. Hannah, Leslie. “The Divorce of Ownership from Control from 1900: Re-Calibrating Imagined Global Historical Trends.” Business History 49 (2007): 404– 438. Harris, Ron. Industrializing English Law: Entrepreneurship and Business Organization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. Hilt, Eric. “When Did Ownership Separate from Control? Corporate Governance in the Early Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Economic History 68 (2008): 645– 685. Holderness, Clifford G. “The Myth of Diffuse Ownership in the United States.” Review of Financial Studies 22 (2009): 1377– 1408. Jefferys, J.B. Business Organisation in Great Britain 1856– 1914. New York: Arno Press, 1977. Klerman, Daniel, and Paul G. Mahoney. “Legal Origin?” Journal of Comparative Economics 35 (2007): 278– 293. Lamoreaux, Naomi R., and Jean-Laurent Rosenthal. “Legal Regime and Contractual Flexibility: A Comparison of Business’s Organizational Choices in France and the United States during the Era of Industrialization.” American Law and Economics Review 7 (2005): 28 – 61. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “Corporate Ownership Around the World.” Journal of Finance 54 (1999): 471– 517. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “Government Ownership of Banks.” Journal of Finance 57 (2002): 265– 301. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. “The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins.” Journal of Economic Literature 46 (2008): 285– 332. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. “Legal Determinants of External Finance.” Journal of Finance 52 (1997): 1131– 1150. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. “Law and Finance.” Journal of Political Economy 106 (1998): 1113 –1155. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. “Agency Problems and Dividend Policies Around the World.” Journal of Finance 55 (2000): 1 –33. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. “Investor Protection and Corporate Governance.” Journal of Financial Economics 58 (2000): 3 – 27. La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, Andrei Shleifer, and Robert W. Vishny. “Investor Protection and Corporate Valuation.” Journal of Finance 57 (2002): 1147–1169. Levine, Ross. “The Legal Environment, Banks, and Long-Run Economic Growth.” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 30 (1998): 596– 613. Levine, Ross. “Law, Finance, and Economic Growth.” Journal of Financial Intermediation 8 (1999): 8 –35. Levine, Ross, Norman Loayza, and Thorsten Beck. “Financial Intermediation and Growth: Causality and Causes.” Journal of Monetary Economics 46 (2002): 31 – 77. Licht, Amir N., Chanan Goldschmidt, and Shalom H. Schwartz. “Culture, Law, and Corporate Governance.” International Review of Law and Economics 25 (2005): 229–255. Lipartito, Kenneth, and Yumiko Morii. “Rethinking the Separation of Ownership from Management in American History.” Seattle University Law Review 33 (2010): 1025– 1063. Mahoney, Paul G. “The Common Law and Economic Growth.” Journal of Legal Studies 30 (2001): 503– 525. Malmendier, Ulrike. “Law and Finance ‘At the Origin’.” Journal of Economic Literature 47 (2009): 1076– 1108. Malmendier, Ulrike. “Roman Law and the Law-and-Finance Debate.” University of Berkeley mimeo (2010). Merryman, John H. The Civil Law Tradition: An Introduction to the Legal Systems of Western Europe and Latin America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1969. Michaels, Ralf. “Comparative Law by Numbers? Legal Origins Thesis, Doing Business Reports, and the Silence of Traditional Comparative Law.” American Journal of Comparative Law 57 (2009): 765– 796. Morck, Randall K., and Lloyd Steier. “The Global History of Corporate Governance: An Introduction.” In A History of Corporate Governance around the World, edited by Randall K. Morck, 223– 282. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. Morck, Randall K., and Bernard Yeung. “Economics, History, and Causation.” Business History Review 85 (2011): 39 – 53. Business History 19 Mulligan, Casey B., and Andrei Shleifer. “Conscription as Regulation.” American Law and Economics Review 7 (2005): 85 –111. Musacchio, Aldo. “Can Civil Law Countries Get Good Institutions? Lessons from the History of Creditor Rights and Bond Markets in Brazil.” Journal of Economic History 68 (2008): 80 –108. Musacchio, Aldo. “Laws Versus Contracts: Legal Origins, Shareholder Protections, and Ownership Concentration in Brazil, 1890–1950.” Business History Review 82 (2008): 445– 473. Musacchio, Aldo. Experiments in Financial Democracy: Corporate Governance and Financial Development in Brazil, 1882– 1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. Musacchio, Aldo. “Law and Finance c.1900.” NBER Working Paper 16216 (2010). Nunn, Nathan. “The Importance of History for Economic Development.” Annual Review of Economics 1 (2009): 65 – 92. Pagano, Marco, and Paolo Volpin. “The Political Economy of Corporate Governance.” American Economic Review 95 (2005): 1005– 1030. Perotti, Enrico C., and Ernst-Ludwig von Thadden. “The Political Economy of Corporate Control and Labor Rents.” Journal of Political Economy (2006): 145– 174. Pistor, Katharina. “Rethinking the ‘Law and Finance’ Paradigm.” Brigham Young University Law Review (2009): 1647– 1670. Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. “The Great Reversals: The Politics of Financial Development in the Twentieth Century.” Journal of Financial Economics 69 (2003): 5 – 50. Roe, Mark J. “Legal Origins and Modern Stock Markets.” Harvard Law Review 120 (2006): 460– 527. Roe, Mark J., and Jordan L. Siegel. “Political Instability: Effects on Financial Development, Roots in the Severity of Economic Inequality.” Journal of Comparative Economics 39 (2011): 279–309. Sarkar, Prabirjit, and Ajit Singh. “Law, Finance and Development: Further Analyses of Longitudinal Data.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 34 (2010): 325– 346. Sgard, Jérôme. “Do Legal Origins Matter? The Case of Bankruptcy Laws in Europe, 1808– 1914.” European Review of Economic History 10 (2006): 389– 419. Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert Vishny. “A Survey of Corporate Governance.” Journal of Finance 52 (1997): 737– 783. Shleifer, Andrei, and Daniel Wolfenzon. “Investor Protection and Equity Markets.” Journal of Financial Economics 66 (2002): 3 – 27. Spamann, Holger. “The ‘Antidirector Rights Index’ Revisited.” Review of Financial Studies 23 (2010): 467– 486. Stulz, René M., and Rohan Williamson. “Culture, Openness, and Finance.” Journal of Financial Economics 70 (2003): 313– 349. Sylla, Richard. “Schumpeter Redux: A Review of Raghuram G. Rajan and Luigi Zingales’s ‘Saving Capitalism from the Capitalists.’.” Journal of Economic Literature 44 (2006): 391– 404. Wurgler, Jeffrey. “Financial Markets and Allocation of Capital.” Journal of Financial Economics 58 (2000): 187– 214. Xu, Guangdong. “The Role of Law in Economic Growth: A Literature Review.” Journal of Economic Surveys 25 (2011): 833– 871.