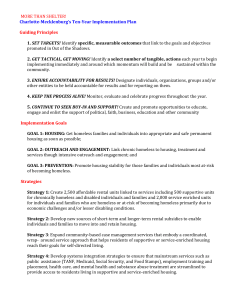

HOMELESSNESS: Programs and the People They Serve Findings of the

advertisement