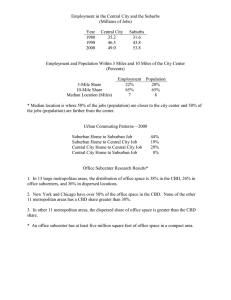

Poverty Suburbanization: Theoretical Insights and Empirical Analyses Kenya L. Covington

advertisement