California State University, Northridge

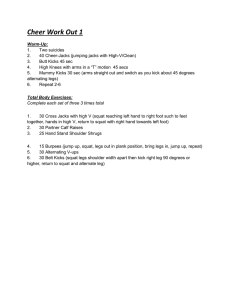

advertisement