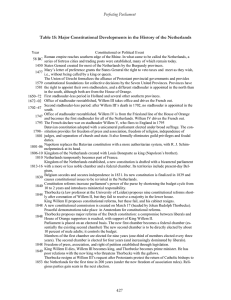

Chapter 15: Constitutional Reform in the Netherlands: from Republic, to

advertisement