Chapter 12:The Emergence of Democracy in the Kingdom of the

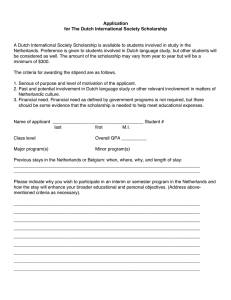

advertisement