America’s Neglected Debt to the Dutch, An Institutional Perspective

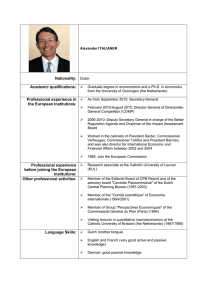

advertisement