National Perspectives on Housing Rights – Ireland. 13

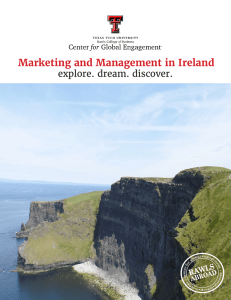

advertisement