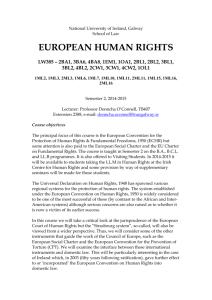

Local Authorities and the European Convention on Human Rights Act 2003 Introduction

advertisement