CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE AMERICANS BEHIND THE BARBED WIRE:

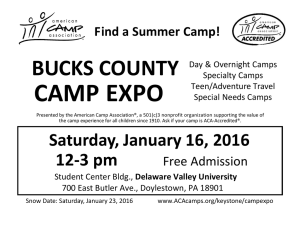

advertisement