CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE RESTORING HOPE WITHIN AN INVISIBLE POPULATION:

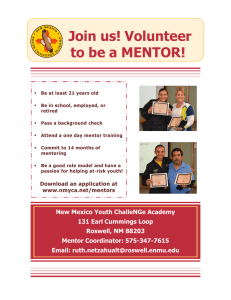

advertisement