The evolution of customised executive education in supply chain management

advertisement

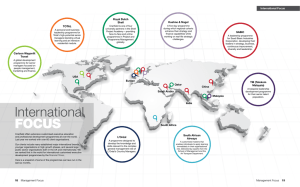

The evolution of customised executive education in supply chain management Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Cranfield School of Management, Cranfield University, Cranfield, UK Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to explore the evolving nature of supply chain management customised executive education over the past decade and present a conceptual framework for curriculum development and design. Design/methodology/approach – The paper adopts a combination of methods utilising both in-depth interviews with academics and practitioners and a single longitudinal case study based on records of 197 customised executive education programmes delivered since 2000. Findings – The findings show that the needs of practitioners have evolved from acquiring competency-based training to obtaining support for wider strategy deployment and change management programmes within organisations. Moreover, the design and delivery of programmes have developed over the period considering the requirements for experiential learning, project work involving deeper faculty engagement, pre- and post-course project activity, supported by internet-based learning portals. Research limitations/implications – The authors’ research provides evidence that the nature of supply chain executive education has changed and that further research is needed to explore the implications for the delivery of programmes. Practical implications – The adoption of the framework will provide course directors and programme managers involved in supply chain management executive education with insights for successful design and execution of programmes. Similarly, the framework can support decisionmaking processes conducted by organisations commissioning customised executive education programs. Originality/value – Although there is a body of research relating to curriculum development and design generally, there is little empirical research focusing on supply chain management executive education. Keywords Supply chain management, Executive education, Training, Adult learning, Andragogy Paper type Research paper Introduction role that supply chain programmes have in supporting organisational change. In this paper, we focus on the relationship between the emergence of SCM as an integrating discipline within organisations and the customisation of executive education programmes to support the successful implementation of SCM change programmes. More specifically, the paper addresses two research questions: The field of supply chain management (SCM) has emerged over the past decade from a functional perspective whose central focus was the management of the physical distribution of goods, to a multidisciplinary concept where supply chains compete as a whole utilising global networks (Christopher, 2010). This has produced significant changes in organisational culture, structures, information systems capability and operating planning processes. Many organisations have relied on executive education programs to help drive these changes (Büchel and Antunes, 2007; Kets de Vries and Korotov, 2007; Freeman and Cavinato, 1992; Giunipero et al., 2006; Carter et al., 2006). Although there is clear evidence in the literature of the growing importance of SCM, there is a dearth of empirical research reporting on the changing role of executive education. Through the use of case study research and expert interviews, we seek to explore the engagement of providers of supply chain executive education to support the delivery of strategy and behavioural change and the emerging RQ1. How has supply chain management executive education changed in the last decade? RQ2. What are the implications of contextual changes for providers of executive education in supply chain management? To address these questions empirical data have been used to develop a framework that maps three key stages in the evolution of executive education in SCM and details the key relational, educational and design characteristics of programmes in SCM. Following this introduction we present a literature review discussing executive education in SCM. The methodology section discusses the research design and the methods for data collection and analysis. The findings section presents the results obtained from the analysis of the records provided and The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1359-8546.htm Received July 2012 Revised October 2012 November 2012 Accepted November 2012 Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 18/4 (2013) 440– 454 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited [ISSN 1359-8546] [DOI 10.1108/SCM-07-2012-0262] 440 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 the interviews, focusing on three illustrative programmes to exemplify the different educational characteristics. The discussion section presents the “Supply Chain Management Executive Education Framework” which was developed inductively, based on the findings. Finally, we discuss the conclusions, limitations and opportunities for further research. that to learn we start with concrete experiences, followed by a period of reflection. Reflection in turn leads to a conceptualisation of the experience which can be used to make decisions and act on them. Participants in executive education courses already have concrete experiences to build on, but often lack the time and space to reflect on them and develop conceptualisations. Executive education can provide time and space for practitioners, helping them to solve pressing problems and improve their performance at work (Garvin, 2007). Another important consideration in executive education, and indeed in any other form of education, is to recognise that students have different learning styles. Honey and Mumford (1982), classify learning styles into four categories: 1 activists; 2 reflectors; 3 theorists; and 4 pragmatists. Literature review Teaching and learning in executive education Executive education programmes serve needs at both the individual and organisational level. For individuals, the goals can include acquiring knowledge and understanding of a particular subject, improving performance at work, and finding help to resolve specific problems (Garvin, 2007). For organisations commissioning executive education, programmes represent drivers for change (Kets de Vries and Korotov, 2007), “both the nuts-and-bolts of change and the leadership of change” (Büchel and Antunes, 2007, p. 403). Central to both individual and organisational goals of executive education is the process of learning. Learning is a complex construct because it involves a range of different activities such as understanding, recognising, remembering, mastering, reasoning, debating, and developing behaviour (Fry et al., 2003). These activities ultimately lead to meaning and can potentially change the way we perceive and understand the world (Morton and Booth, 1997). One of the most prominent theories of learning is constructivism (Piaget, 1950; Bruner, 1960, 1966), which proposes that people learn by continuously building and amending structures and constructs as new experiences are assimilated (Fry et al., 2003). If these structures do not change, learning will not take place. The constructivist perspective promotes the use of reflection, understanding and experiential learning and opposes more traditional methods of teaching that focus on passive learning and memorisation (Fry et al., 2003). The use of experiential learning or action-learning methods is particularly relevant in an executive education context, where most course participants are mature students with business experience and good understanding of organisational realities and management practices (Garvin, 2007; Newman and Stoner, 1989). Often what they look for in executive education is a larger framework or theory from which they can make sense of their own experiences (Garvin, 2007). The use of teaching and facilitation methods that promote actionlearning such as simulations, case studies, specific problems and projects is common in many business schools (Beaty, 2003). Furthermore, in executive education, action-learning programmes have shown to enhance both individual and organisational outcomes compared to traditional formats (Tushman et al., 2007). Experience alone will not necessarily lead to better understanding and learning. If experiences are to generate learning it also is important to reflect on them and assimilate them (Beaty, 2003). Kolb (1984, 1993) conceptualised a model of experiential learning based on the learning models of Lewin, Dewey and Piaget (Kolb, 1993). His model proposes It is impossible to box business executives into any of these categories, and their preferred learning style could combine elements of several categories. Nevertheless, Garvin (2007) asserts that participants in executive courses often have a more pragmatic approach to education, have specific problems in mind when attending courses and are less motivated by intellectual concerns. This would indicate that they tend to be more pragmatists or activists, rather than reflectors or theorists. Recognising and understanding these learning styles can support the design of courses that can cater for all these learning styles ensuring individuals are not being left behind. Executive education participants are mature students and they tend to approach learning in different ways (Fry et al., 2003). The concept of andragogy, defined by Knowles (1984) as the “art and science of helping adults learn” is very relevant in an executive education context. Knowles (1980) characterises adult learners as: . being mature and self-directing; . bringing learning situation resources from their previous experience and training that is a rich resource of one another’s learning; . being task-centered, problem-centered and life-centered in their orientation to learning; . being intrinsically motivated to learn. Knowles (1974) contrast the traditional model for child education (i.e. pedagogy) with that for the education of adults (Andragogy) and argues that the inherent differences in the learner require a different model of education. For adults, he advocates a process model rather than a content model; a model that is “concerned with providing procedures and resources for helping learners acquire information, understanding, skills, attitudes, and values” (Knowles, 1974, p. 117). The andragogical approach, according to Knowles (1974, 1979), requires changing the assumption that education consists of transmitting knowledge, and accepting that adult education represents a process of acquiring skills, attitudes and values, as well as knowledge (Knowles, 1979). This also requires the educator to change its approach and become a 441 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 facilitator of learning and a resource provider (Knowles, 1979). Understanding the goals of executive education students, their learning styles, and the general characteristics of adult learners are important elements in designing, delivering and assessing courses to meet specific requirements. In the case of customised education it is also necessary to take into consideration the needs of the organisation, which will often include a transformational agenda (Kets de Vries and Korotov, 2007). Executive education in supply chain management combines the challenges of general executive programmes with the technical complexities of the subject matter. The following section concentrates on the literature of SCM education and its implications for executive education. required are technical (e.g. transport, logistics, network design, inventory management). However, Giunipero et al. (2006) argue that supply chain management has taken a more strategic role in organisations creating a need for more strategic skills (e.g. leadership, influencing, planning). Table I categorises the different skills required from SCM professionals as purported in the literature: Freeman and Cavinato (1992) evaluate an executive course in procurement and argue that executive education is frequently used as a mechanism to transform a functional area “from a reactive stance to one that fulfils a critical role in the strategic management of the firm” (Freeman and Cavinato, 1992, p. 25). This transformational role requires practitioners to build on their technical/functional skills, to develop more general management skills and ultimately leadership and strategy skills. In this respect, Table I could be interpreted as a staircase in which executive education is designed to move participants upwards. Supply chain management executive education Supply chain management (SCM) is a nascent field which started to be incorporated into syllabi during the 1990s (Johnson and Pyke, 2000), and research into SCM education is relatively scarce. Existing research tends to focus on undergraduate and postgraduate courses (e.g. Johnson and Pyke, 2000; Rock Kopczak and Fransoo, 2000; Carter et al., 2006; Birou et al., 2008; van Hoek et al., 2011), overlooking executive education. Educational research is more developed in subjects that are closely associated with SCM, such as logistics, transport and procurement. For the purpose of this paper we have decided to take a unionist perspective (Larson and Halldorsson, 2004) and draw on educational developments in all of these subjects to create a broader picture of SCM education The literature proposes various models to describe the knowledge and competencies that supply chain professionals apply – see McKevitt et al. (2012). Gammelgaard and Larson (2001) suggest a three-factor model of supply chain management skills, which they interpret as interpersonal/ basic managerial skill, quantitative/technological skill, and core SCM skills, while Mangan and Christopher (2005), in a survey of supply chain professionals, rank their skills as communication followed by people management and problem solving. Gravier and Farris (2008) conducted a review of the educational literature in logistics from the 1960s through to 2008, and identified 81 relevant articles. They categorised the publications in three primary themes: content and skills, curriculum development and delivery methods. Of these three themes, curriculum has received the most attention, with 60 per cent of the papers, however, teaching methods, which accounted for 21 per cent of the papers, did not emerge until the 1990s and has received substantial attention since then (Gravier and Farris, 2008). The categorisation of Gravier and Farris provides a useful structure for discussing education in the broader field of SCM and has been used to structure the remainder of this section. Curriculum development The literature on curriculum development for executive programmes in supply chain management is practically nonexistent. However, a number of studies have analysed and recommended curricula for supply chain education, mainly with a focus on undergraduate studies (e.g. Johnson and Pyke, 2000; Lancioni et al., 2001; Myers et al., 2004; Wu, 2007; Gravier and Farris, 2008; Birou et al., 2008). The main focus of undergraduate and even post-graduate courses tends to be on technical/functional areas, with general management, and strategy and leaderships receiving lesser attention. van Hoek et al. (2002), highlight a similar issue, claiming that teaching in supply chain management tends to focus on technical aspects and overlook the human aspects. They argue for education that is more strategic and more sensitive to emotional aspects. In one of the few publications on open executive education in a field related to SCM, Freeman and Cavinato (1992) evaluate the “Strategic Purchasing Management Program” delivered at Penn State University (USA). They argue that to give a new perspective it is necessary to provide not just a programme, but an “educational experience” to teach the participants the “language and culture of general management”. Further, they claim that to deliver this objective the content of the course has to focus on general management subjects such as: strategic management, finance, organisational structures, international business, and communications (Freeman and Cavinato, 1992). It appears that while undergraduate and postgraduate students with limited work experience require a heavy load of technical and functional courses, executives need a different balance with greater emphasis on general management, finance, leadership and strategy. Delivery in executive education in SCM The differences between undergraduate/postgraduate and executive education also affect delivery methods. Freeman and Cavinato (1992) argue that executive educational needs are to be highly interactive and include case studies, discussions and simulations to help participants understand the implication of their decisions on the competitive Content and skills Supply chain management education is often targeted at developing professionals that can apply their skills and knowledge in organisations. Hence, it is important to understand the skills demanded by the profession as a starting point to develop the curriculum. Many of the skills 442 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 Table I Skills in supply chain management Theme Skills Sources Leadership and strategy Strategy formulation, influencing, leading change, negotiation, compromising, team building facilitation, innovation, entrepreneurship Freeman and Cavinato (1992); Giunipero et al. (2006); Carter et al. (2006) Financial Accounting, activity based costing (ABC), total cost analysis, break even analysis, writing business cases Giuinipero and Handfield (2004); Giunipero et al. (2006) General management Goal setting, decision-making, problem solving, creative thinking, execution, communication (writing, presentation, listening), project management, change management, information systems, time management, risk management, human resource management Carter et al. (2006); Giunipero et al. (2006); Gravier and Farris (2008); Myers et al. (2004) Technical/functional Transport, logistics, procurement, supplier selection, network design, materials management, Inventory/JIT, operations management, quality and service, simulation and modelling Giunipero et al. (2006); Gravier and Farris (2008) lead to the same learning as resolving a real problem for an organisation. Carter et al. (2006) provide one of the few publications discussing customised executive education in supply chain management. The key difference in customised education is that a single organisation, with specific needs, reaches out to the academic community for a program to educate their executives. Based on reflections over a three year executive education program for IBM, Carter et al. (2006) offer advice to organisations looking to buy executive education programmes in supply chain management. They propose seven prescriptive recommendations summarised in Table II. The recommendations offered by Carter and colleagues are useful for academics because they give an indication of what customers of executive education in this field are looking for. This has implications for course design, delivery methods and faculty expertise and skills. For instance, point 1 implies that educational institutions might need to look for partners, to landscape of the organisation. Furthermore, they argue that executive education should equip participants with the tools to lead transformational change (Freeman and Cavinato, 1992, p. 30). Rock Kopczak and Fransoo (2000) provide a good example of how to improve the understanding of the “soft” issues through the use of global projects with global project teams. They describe how Master level students from Stanford, Eindhoven University of Technology and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology would form teams and companies that resolve specific problems. This approach helps students learn about general management issues in a supply chain and although not applied to executive education, elements of this problem-based learning approach should be applicable to practicing executives. A less expensive and time consuming way of embedding “insights from industry” in supply chain programmes is to use guest lecturers as argued by van Hoek et al. (2011), although it is unlikely that this will Table II Recommendations for executive education programmes in SCM Recommendation Rationale 1. Consider drawing from multiple providers To include diverse expertise and perspectives to avoid groupthink ant to benefit from a broader selection of faculty 2. Include some element of project work or action planning This will help to facilitate knowledge and skill transfer when participants return to their organisations 3. Incorporate some aspect of experiential learning such as case study or simulation To enhance involvement of participants and help them to visualize the links between strategy and decision making 4. Ensure that providers can incorporate a strong global component Most supply chains are global and this should be reflected in the design of the programme 5. Integrate the design of the programme with the evaluation and advancement programme To ensure programme is used to support the career development of the participants 6. Programme coordinators should monitor the results for the action plans Organisations want to see changes in performance from participants 7. Measure deliverables against programme objectives Organisations went to know if the programme is delivering against an initial set of objectives Source: Developed by authors based on Carter et al. (2006) 443 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 satisfy the clients’ needs. Points 2 and 3 call for case studies, action learning and experiential learning materials as well as faculty with appropriate facilitation skills and technical knowledge. Point 4, could be handled in different ways, including collaboration with institutions in other parts of the world as well as international faculty who can provide a global perspective. Finally points 5, 6 and 7, indicated that a substantial amount of work might be required after the course to evaluate performance and support participants’ action plans. The studies by Freeman and Cavinato (1992) and Carter et al. (2006) may have methodological limitations because they focus on single cases. However, they are useful because they provide a clear indication that executive education in SCM, and particularly customised education, is substantially different from traditional education and places different demands on the faculty designing and delivering this type of course. Both studies provide stepping stones to continue investigating this relatively unexplored subject. phenomenon and its surrounding context (Voss et al., 2002; Meredith, 1998). Furthermore, the mixed methods approach improved the reliability, as well as the internal and external validity of the study. Selection of case study and interviewees The academic institution selected for the case study provides a unique setting for the research because it has been involved in executive education in the field of supply chain management, logistics and transportation for over 25 years. Detailed records of programmes including learning objectives, number of participants, programme duration and timetables are available providing a rich source of longitudinal data to be analysed. In total, 197 programmes with 49 different organisations, accounting for 4623 delegates during the period 1st January 2000 through to 31st May 2012, were included in the study. Two types of interviewees were involved in the research: practitioners and academics. Focus groups had been considered as they may have afforded more interaction but, due to the geographies involved, were not feasible. Interviews with practitioners were selected on either the basis of holding a senior supply chain role or a senior role within a human resource function with direct involvement in SCM executive education. Eight interviews with practitioners were conducted within three different organisations. These three organisations are used as illustrations of customised programmes in the findings section. Academic interviewees were selected on the basis of their involvement on executive education with particular emphasis on supply chain programmes. Seven interviews with academics from five different institutions in the UK (Cranfield and Oxford), the USA (MIT and Babson) and France (HEC Paris) were conducted. All of the academics interviewed have at least ten years’ experience in executive education and two of them have over 40 years’ experience. Two of them are currently heads of executive education in their respective institutions and two of them are former heads. The remaining three have acted as course directors for numerous executive education courses. The purpose of these interviews was to understand changes in the executive education market and the response of academic institutions to these changes in andragogical terms. Methodology This study investigates changes in customised executive education in supply chain management. Given the exploratory nature of the research, we decided to use a mixed methods approach (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Leonard-Barton, 1990) combining a single longitudinal case study using archival data and a series of 15 interviews with academics and practitioners. These methods are both complementary and synergistic and help to overcome some of the weaknesses of using each of the methods independently. The longitudinal case study involved the analysis of a population of 197 archival records of supply chain customised executive programmes delivered by a single UK-based academic institution since 2000. Each individual programme was treated as a unit of analysis providing a basis of comparison. The benefit of this approach is that it allowed unique access to unique factual data that has been systematically recorded over a long period of time. This helps increase the study’s internal validity by allowing the investigation of causal links (Leonard-Barton, 1990). Semi-structured interviews with both academics delivering executive education programmes and practitioners involved in acquiring customised executive programmes. The interviews helped to understand the contextual changes in the executive education market, the changing needs of organisations and supply chain practitioners, and the educational approaches used by institutions to satisfy the needs of executive education clients. Semi-structured interviews provided flexibility to explore an under-researched phenomenon (Oppenheim, 2001; Bryman and Bell, 2007) and provided an opportunity to investigate the phenomenon from the perspectives of both the consumer and the educator (Burgess, 1982, p. 107, in Easterby-Smith et al., 2008). These interviews strengthen the external validity of the research by allowing triangulation and allowing the investigation of the phenomenon from different vantage points. The combination of methods and data helped gain rich empirical results and a deep understanding of the research Analysis of archival records Four main sources of archival records were analysed. Information was retrieved from the electronic accounting system to provide transaction data including, company name, programme title, programme duration, number of delegates, delegate names, and whether the programme was run on-site at the academic institution or off-site. Further analysis relating to course content was undertaken by reviewing the individual course timetables and course presentation media. The timetables contained the title of each individual session, the duration and the facilitators’ name(s). The detailed course content was retained in the Powerpoint presentations used in the programmes that were stored on the University databases. Finally, the course appraisal sheets were also used to gather information on delegate feedback. The appraisal forms were 444 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 not stored electronically but were archived at the University’s store rooms. Purposeful sampling was used to select only executive education programmes that were solely based on supply management themes. As a consequence, a significant number of general management programmes, where supply chain concepts were an element of the overall course specification, were omitted from the analysis. Despite the increasing maturity some of the interviewees have also acknowledged that there is a skills and knowledge gap and that education is still required. The need for skills is greater than it’s ever been. Globalisation Many supply chains were global a decade ago. The process of globalisation has continued, creating more complex and interconnected supply chains. One of the interviewees has noted: Analysis of interviews and secondary data Interviewees were initially contacted by e-mail and provided with a background to the research and the semi-structured interview protocol in advance of meeting. Following agreement to take part, the duration of interviews ranged from thirty minutes to two hours. To supplement the interviews, secondary data was also collected including company documentation and archival records specifically concerning the objectives, design, delivery and appraisal of programmes. Combining primary and secondary sources of data provided validation through triangulation (Yin, 2008). Notes were taken during the interviews and the data analysed through the identification of emergent patterns (Glaser and Strauss, 1967; Yin, 2008). Following the data analysis the initial findings were e-mailed to the participants to verify that their views had been correctly interpreted. We’re managing global supply chains and there is a need to understand the intricacies of global logistics. Many of these skills now live in large logistics companies. This globalisation process also has implications for education as practitioners around the world have access to the same knowledge. One interviewee has commented: The world is flat, distance in learning opportunities is smaller. We have more access to knowledge; now it’s about how we use this knowledge. Competition Most of the interviewees have noted that competition in executive education has increased substantially over the last ten years. Academic institutions have strengthened their offerings and some have developed a global reach, but the greatest challenges have come from other types of organisations, such as, consultancies, professional organisations and small niche players. The following quotes exemplify this trend: Findings 10 years ago there were few universities doing SCM. Now every university has a programme. To answer the first research question “How has supply chain management executive education changed in the last decade?” we initially looked for general trends in the archival data. Table III shows the total number of programmes considered in the study, detailing the location of the program and the average number of participants. Table IV shows the average number of days per programme since January 2000 and Figure 1 presents a breakdown of the programmes by industry sector showing a wide variety of industries involved, with logistics and service providers being the dominant sector, followed by retail, home and personal care and food and drink. The interviews with academics provide much greater depth concerning the contextual factors that have affected customised executive programmes in recent years. Based on these interviews five key trends affecting supply chain management education over the past decade were identified: maturity, globalisation, competition, technology, and change management. Each of these is briefly discussed below: Other organisations, such as, CIPS and CILT have also entered the market, covering specific subjects such as warehousing, etc. Consultants have always been in the frame, but now they are doing more knowledge into action. . . This trend has pushed universities to be more competitive in terms of their offering. One of the interviewees has claimed: We are really being pushed on the value; consultancies coming into the marketplace, start-up organisations and small “niche” players and other challengers of ideas from outside business schools. Change management Another trend that has been consistently recognised by interviewees is that customised programmes are being used for transformational purposes. They are often part of a larger change management agenda in which education is used partly to provide knowledge and skills and partly to legitimize the change initiative. The following quotes support this view: Today companies have very specific requirements, normally around a significant change management programme. For customised programmes it’s important to clarify the “real” objectives, which are often beyond supply chain training. Maturity Supply chain management has developed substantially over the past decade. Practitioners are now familiar with the terminology and companies accept it needs to be managed. Increasing maturity has implications for the depth and breadth of programmes. The following quotes exemplify these changes: These changes are also affecting the design of programmes, the educational approaches used and the relationship with the clients. This is evident from the following quotes: 10 years ago it was about awareness rising. Now it’s moved to addressing specific business problems and resolving them. It’s more how-to and implementation. Before, action learning would be on the job. Now the runway is shorter and it requires a different kind of executive education. We need much more action learning and experiential learning. Courses are targeted at changing hearts and minds and supporting the new strategy. The university is used to gain external credibility. 445 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 Table III Number of organisations and executive education programmes – 1 January 2000 to 31 May 2012 Total number of organisations Total number of individual programmes Number on-site Number off-site Average number of delegates per programme 197 164 33 23 49 Table IV Average number of days per programme 2000 to 2012 Average number of days/programme 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 3.2 3.3 3.6 3.8 3.6 3.5 4.6 5.8 7.1 4.7 3.3 3.4 2.3 Figure 1 Companies by sector Programmes are highly customised, taking up to a year or longer to develop and pilot material. These require a much greater level of intimacy with the client. A classification of programmes From the coding of the programme objectives, timetables and company documentation three main themes emerged: . Knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes. . Specialist technical programmes. . Strategic support programmes. Technology Changes in technology have affected both the content of programmes and the tools used in education. Although technological changes are perhaps obvious and natural it’s important to recognise the changes they can bring. One of the interviewees has noted that technology was very influential in SCM at the turn of the century, but technology is less significant today. He claimed that: Knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes These programmes are designed to cover a broad spectrum of general supply chain concepts and technical subjects with the objective of raising the overall awareness of supply chain theory and bridge a knowledge gap within an organisation. As an example, it was noted in our interviews that in a response to customers increasing needs or more complex supply chain services, the logistics service provider (LSP) sector had recognised a need to raise the standard of their organisations overall supply chain knowledge. Several major LSP’s had therefore used knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes as part of this initiative. These programmes often have a number of iterations (or cohorts) that repeat several times per year over several years to immerse or “sheep dip” a large number of personnel within an organisation. Typical objectives for these programmes included: At the turn of the century there were technological advances, such as, ebusiness that dominated the agenda, now the need is organisational change. The impact of technology is also significant for the educational process as new tools such as webinars and podcasts have become popular. One of the interviewees has noted: 10 years ago it was mainly class, now there is more pre-learning, webinars, on-line exercises, filming, podcasts. The changes outlined above have affected both the content and the design of programmes. In the following subsection we’ll classify different types of programmes before illustrating the impact of these changes using specific programmes. To expose delegates to the latest in supply chain thinking. 446 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 planning. Delegate numbers range between 18- 30 and the length of programmes were typically 3-5 days. To support a consistent and integrated approach to supply chain management across the business. To embed a common “language” within the supply chain functions. Specialist/technical programmes Specialist/technical programmes have a narrow subject focus or emerging theme. They typically involve teaching practitioners in more operational roles and provide a detailed examination of the subject matter often with hands on training. They are normally shorter in duration than skills gap/sheep dip programmes and have a smaller number of total delegates due to the specialist nature of the training – between 10 and 20. Examples of programmes include: . Warehousing. . e-Procurement: from strategy to value. . The changing role of logistics service providers in Europe. . Inventory optimisation – tools and techniques. . Supply chain mapping. . Design of distribution centres The curriculum for this kind of programme would exhibit a high level of commonality. The educational approach combined traditional lectures with experiential learning, mainly through published case studies, business simulation games, exercises and activities. Extracted from the timetables, Table V illustrates the most highly used supply chain concepts, case studies, business games and exercises used for these programmes. The analysis revealed that as the influence of the Supply Chain Councils’ SCOR framework (Supply Chain Council, 2010) has increased, the structure of programme timetables have increasingly been aligned to their key of “Plan, Source, Make, Deliver and Return” process model. A mixture of learning methods would be deployed in support of more formal lectures including, cases studies, business simulations and games and exercises. Delegates would be exposed to short buzz sessions, group exercises and break-out sessions, open debate, reflection periods, journal writing, and general action Strategic support programmes From the analysis of the data contained in the programme objectives and timetables, a clear trend was established. Between 2000 to 2005, the majority of programmes were knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes or specialist/technical programmes with a small number coded as “Others” (for example, senior management briefings/workshops and company annual conferences) forming the remainder. From 2006 to 2012 strategic support programmes emerged and now form the majority of programmes as illustrated in Figure 2. These programmes require a highly customised design whose purpose is to support the delivery of strategy deployment and business transformation for companies. Archival records show that these programmes demand significant engagement between the client and the academic institution, ranging between 6-18 months prior to the commencement of the first programme running. Knowledge gap/sheep dip and specialist/technical programmes in supply chain management are, for the most part, well established and the mechanisms for their design and delivery are well understood. Conversely, there is little in the literature that explores the characteristics of strategic support programmes. The next section seeks to bridge this gap by presenting empirical data from three illustration programmes. Table V Knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes: repeating themes, SCM concepts taught, cases studies, business games and exercises SCM concepts Introduction to supply chain concepts Managing global supply chains Agility/lean and leagile supply chains Forecasting and inventory management Manufacturing operations in a supply chain context Strategic sourcing and procurement Distribution and warehouse operations IT and software selection Supply chain finance Lean and time compression Collaboration Supply chain performance measurement Outsourcing and third party logistics Sales and operations planningj Change management Case studies Dell Marks & Spencer Li & Fung Super models – time compression Zara – fast fashion Finn Forest Scotts Hewlett Packard Mattel and the Toy Recalls Illustration programmes Illustration programme Alpha Alpha is one of the world’s leading international oil and gas companies. Its main activities include the exploration and extraction of oil and gas, moving and making fuels and products and providing its customers with fuel for transportation, energy for heat and light, retail services and petrochemical products for everyday items. To maximise the value of its operations, during 2008 the company embarked on a major restructuring of its global refining, logistics, retail and marketing functions around a business strategy called fuels value chain (FVC). The concept was to integrate all the elements of the business into a single value chain to meet customer demands and enhance profitability. The company also set about changing the way Business games Supply chain game – manual simulation of a multi echelon supply chain Supply chain game simulation – computer based simulation with costs and service objectives Exercises Demand forecasting Inventory management Lean and time compression Network design 447 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 Figure 2 Percentage of programmes delivered 1 January 2000 to 31 May 2012 electronic presentation media, including, strategy reports, examples of commercial defined practices, and “the way we work” report. It took nine months to develop the first pilot programme. To ensure the quality of the programme, a “dry run” was performed at the company’s head office where the material was “walked through” and final amendments were identified. The programme was finally delivered by seven subject experts, one external practitioner expert and four senior managers from the company over three days. of operating and implementing a series of initiatives based on ensuring a more “systematic” way of working across all FVCs. This programme extended to covering major planning processes, such as sales and operations planning (S&OP), operating procedures, such as, safety and a new performance measurement system. The strategy was supported by the central supply chain team who set the standards and published a series of “commercial defined practices” and a capability framework. Historically, the company developed and delivered most of their training in house. In a break from this trend they looked to an external provider to support the development needs for the FVC initiative. After the initial tendering process the academic institution was selected as the supplier in June 2011 and the first pilot executive programme ran in March 2012. The company had a very clear set of objective and the programme content needed to be highly customised to address these. They were: . To embed the mindset and behaviours necessary for a systematic management approach. . To provide a comprehensive understanding of the philosophy, components and processes leading to a systematic management approach through lectures, best practice examples, games, case studies and discussions. . To provide executive development and education in supply chain excellence, commercial business management, performance measurement, change management, project management, and knowledge management. Illustration programme Beta Beta is a builders’ merchant and one of the largest suppliers to the UK’s building and construction industry. They provide more than 100,000 products to trade professionals and offer tool and equipment hire services. The company has two main themes to their supply chain strategy: “the language of profit” and “easy to do business with supplier”. The “language of profit” strategy was to embed a culture focussing managers on the goal of profit. This was explained as either growing the business or taking cost out of the business. As the Director of Supply Chain expressed: [. . .] our company is essentially a supply chain business, we have great opportunity to find ways to improve the bottom line by working better across our various businesses. The company’s supply chain senior management team (SMT) worked with the academic institution for six months to develop a programme relevant to colleagues from supply chain, from other functions and from the Group’s trading businesses. The challenge was to design a programme that would support the business strategy by equipping delegates with concepts, methods and techniques that would benefit managers in a wide range of roles, that would promote crossfunctional working and that could demonstrate a clear payback. One of the interviewees commented: Initial meetings were held with senior supply chain executives, including, the Commercial VP – Refining and Marketing and the Global Head of Supply Chain Management, and representatives from the Central Learning and Development function to scope out the core of the programme. A team of academics worked with the central supply chain team, members of the learning and development group and specialists within the company, to create the detailed lesson plans, learning outcomes and develop course materials. The company also provided numerous internal documents and 25 per cent of the material was customised and this was supplemented with examples from us and tailoring of the business games, for example, the supply chain game was adapted to better reflect our supply chain operations. 448 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 The programme was designed for managers across the whole organisation, to develop an understanding of supply chain strategy, best practice and its impact on the business, ultimately delivering strategic benefits of improved customer service, competitiveness and cost and capital control. A significant element of the course was related to supporting post-course project work. Delegates were assigned in groups to pre-defined projects identified by the SMT. The course was specifically designed as a facilitator for the projects in several ways. First, the knowledge transferred during the programme was grounded in relevant supply chain management concepts. Second, it contained tools and techniques for change management and project management. Time was dedicated to the delegates during the programme as “a conscious decision was taken during the design of the course to allow them to work on their projects using tools and templates provided to create their project charters, stakeholder analysis and identify inhibitors and facilitators”. The group working would then be presented back to representatives of the SMT and the academic team and get “agreement and sign off to proceed”. Two months after the programme, the delegates returned to the academic institution for a further development day. They were exposed to additional supply chain improvement tools and reported against the progress of their projects. Finally, after six months, project teams presented their findings to the SMT. Overall, approximately 50 per cent of the programme time was dedicated to facilitating projects. The company saw the programme as part of a deeper engagement with learning and development through sponsoring selected staff for graduate programmes, and also membership of the supply chain research forums. Beta viewed their relationship as a strategic collaboration, going far beyond the provision of courses. The leadership team spent four days at the academic institution in a strategy development workshop to develop a five year transformation plan. To be successful the company recognised two key objectives: 1 A passionate and rigorous approach to putting complex key account customers at the centre of everything we do and building an organisation to deliver this vision. 2 A recognition that these key account customers will require exceptional supply chain knowledge/capability from the organisation/people – and a raising of the bar to have consultant level knowledge and thinking when dealing with board level people in our customers operations. The programme was seen as central to the delivery of the strategy and the curriculum was specifically designed to integrate a series of modules to support a successful transformation. The content included: . Strategic account management . Value selling and account management. . Supply chain and logistics management. The company put in place a balanced scorecard to monitor the success based on a number of key milestones. Discussion Commonalities across programmes The programmes evaluated in this research came from organisations in different sectors, and each had its own distinctive strategy. However, some common themes for their executive education programmes emerge. In all cases, programmes were not seen as a discrete learning and development activities but as part of a wider organisational strategy deployment; an argument that has been highlighted in the literature (e.g. Freeman and Cavinato, 1992; Garvin, 2007; Kets de Vries and Korotov, 2007). The programmes were sponsored by senior management within the organisations; for example, Global Head of Supply Chain Management (Alpha), Group Supply Chain Director (Beta) and National Key Accounts Manager (Gamma). The anticipated outcome for these programmes was to have an immediate and effective behavioural change towards the new strategy with demonstrable results. Care was taken by the companies in selecting managers that would be able to affect change and become advocates of the strategy when they returned to their respective part of the business. It is important to acknowledge that this type of programs have an implicit political agenda within the business involved and the educational institutions play a role in this agenda. Acknowledging this role can help educators decide how they want to engage with the business. Engagement with the companies involved was significant and required the academic institution to have a high level of contact to develop the desired level of intimacy with the company and to have empathy with the delegates. The institutions’ staff made visits to the companies and “buddy up” with nominated company experts to assure the congruence between the strategy and the material being developed. Further, the companies provided internal reports Illustration programme Gamma With 7,000 people and a global network, Gamma is one of the world’s largest freight management companies. They provide customers with integrated supply chain solutions that deliver cargo by sea and air. They operate in several sectors including high-tech, pharmaceuticals, textiles and automotive products and also specialise in marine logistics, industrial projects and other niche markets. They have a network of offices and air and ocean hubs in over 50 countries with a strong presence in Europe, the Americas and the Asia Pacific region. They also have offices in the Middle East and in Africa. In 2008, the company acquired a competitor to gain access to some larger customers and to enhance shipping capability for the UK operation. This integration gave rise to several objectives to be met by the management including: . Manage a successful integration of two organisations with minimal loss of customers. . Establish the new UK Brand as a market leading supply chain and logistics provider. . Significantly increase supply chain capability within the organisations customer facing personnel. . Deliver aggressive growth targets in a competitive market place. 449 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 and PowerPoint presentation media relating to their strategy, operating procedures and other material that would provide relevant background information. The course design also had common elements. Pre- and post-course activity was a significant element for all programmes. Pre-course questionnaires, data collection and some analysis was a pre-requisite along with pre-course reading of case material. Course material was a blend of theory and examples supplemented with company analogies and case vignettes. It was important to all companies that the delegates attending the course should be able “to relate the theory to what’s happening...we are used to doing this ourselves and our people will expect to see lots of our own examples....to some it won’t be normal to get an outside view so we need to be sensitive to this” (Alpha). It was also evident that care was taken so that delegates could immediately see the alignment with their company’s strategy and reflect this directly back to their “day to day” jobs. Examples of this came from the timetables and lesson plans where each company had workshops designed to explore the link between theory and the company. This argument may partly explain the emergence of strategic support programmes as companies look to develop and deploy business wide supply chain strategies. Moreover, companies are looking for external providers who can offer external legitimacy to their strategy so that “the course is not seen as another centre driven initiative....we want to get an external perspective to show how others are doing it and what’s best in class.” It was seen as essential for Strategic Support programmes that the institution needed to have a high level of understanding of the company’s strategy direction and its culture and to “keep our academic integrity but also act in many ways as extension of their own business”. Institutions will need to consider the change in relational forms between delivery of more traditional programmes and strategic supporting programmes. It should also be noted that we found that these relationships can become quite entrenched. As noted by one academic expert, “I can remember working with a company and I felt we had almost gone native and when I heard things were not going their way I felt it too”. As a consequence, strategic support programmes may need a more comprehensive approach to the contract negotiations and careful budgeting to take account of the development period and post-course support. Moreover, the legal aspects for the contracts between the parties may also be more complicated, for example, to take account of the intellectual property from co-developed material, handling and confidentiality of company documentation. Customers of strategic support programmes may also be seeking a deeper relationship with the provider and a broader service offering. Our findings show that many of the companies who received strategic support programmes also engaged in additional service offerings as part of a wider “framework agreement”. Services included, consultancy, memberships to research forums, sponsorship for graduate programmes and support for thesis projects. Consequently, the course director for these programmes acted as relationship manager. Differences across programmes Although a high commonality can be seen among programmes there are some notable differences. Surprisingly, the level of post course activity varied significantly. For one programme, it was a significant component. Cross functional teams of five delegates worked on post course projects and applied their learning to a real business issue within the company. Half-way through the project (a period of six months) the teams returned to the academic institution for a one-day workshop to report on progress and made a final presentation of the results to the supply chain senior management team. For another company, there was no formal post-course activity. The delegates were asked to consider the learning from the programme, to identify further development needs and to present what they will do differently after the course. Our findings build on the literature relating to supply chain executive education (Carter et al. 2006; Freeman and Cavinato, 1992; Rock Kopczak and Fransoo, 2000). Although the literature covers a range of facets pertaining to undergraduate and post-graduate education and general executive education, there is no framework that delineates supply chain executive education programmes and their dimensions. The first contribution of this paper is to present a framework for supply chain executive education, illustrated in Table VI, which identifies two dimensions: 1 relational form; and 2 education and programme design. Programme design The implications for programme design and for the overall educational approach are significant for strategic support programmes. The use of experiential and action learning (Fry et al., 2003; Beaty, 2003; Carter et al. 2006) is consistent with other types of programmes, but Strategic support programmes rely more on problem-based and project-based approaches that focus on existing situations, as well as customised case studies based on the organisation’s current challenges. On the other hand, traditional lectures take a back seat as experienced practitioners “resent being told the facts of life” (Newman and Stoner, 1989, p. 133) and prefer to look for practical applications. These approaches would tend to favour activist and pragmatist learning styles (Honey and Mumford, 1982). In terms of Kolb’s learning cycle (Kolb, 1984, 1993), practitioners already have a wealth of experiences to draw on, but often lack the time to reflect on these experiences and close the cycle. Course materials for strategy support programmes, although based in theory, are co-developed and highly The results indicate that there are several implications for providers of supply chain executive education programmes. First, interviews with academics revealed a recurring observation that the discipline of supply chain had matured over the past decade as implied in such quoted statements: [. . .] supply chain management has now evolved from a functional operation about trucks and sheds and distribution strategy to be a strategically important area to many companies today and they are looking for management schools to deliver more than just training. 450 Knowledge gap/sheep dip programmes 451 Personal action plans None or limited Joining instructions, course objectives, pre-read material Delegate post-course work Post course contact with delegates Information support requirements Delegate pre-course work Deployment of tools and techniques None or limited Joining instructions, course objectives, pre-read material, data collection Low – expertise exists within the academic institution Pre-reading/data collection Embed deep technical skills and expertise to a focussed target group Experiential learning Cooperative learning Case-based learning Game-based/ simulation-based learning Lecturing Semi customised building on established concepts/theory 1-3 Functional experts Provide wide dissemination and knowledge within a wide target group Experiential learning Cooperative learning Case-based learning Game-based/ simulation-based learning Lecturing Based on established theory/concepts and delivery mechanisms 2-5 Middle to senior executives Medium – material is adjusted to suit organisational context Pre-reading Low for both company and institution Fee with limited obligations Single transaction Low level of interfaces between institutional and company personnel; sign off made by a single entity Follow on support for specific technical support Learning and development function Low Programme design and material content led by institutional provider Specialist/technical programmes Low for both company and institution Fee based with limited obligations Single transaction Low level of interfaces between institutional and company personnel; sign off made by a single entity None or very limited Pre-course development time Typical programme duration/days Delegate type Programme content Main educational approaches Resource commitment Contract terms Range of services Programme design Programme objectives Post course contact with delegates Institution/company organisational relationships Relational form Company sponsorship Learning and development function Intimacy with company strategy and culture Low Programme design process Programme design and material content led by institutional provider Factors Table VI Supply chain management executive education framework Pre-reading, attitudinal surveys, personal learning objectives Individual/group based projects Multifaceted support Joining instructions, pre-learning, pre-read material, delegate questionnaires, personal objectives Support and influence behaviours towards business transition programmes Experiential learning Cooperative learning Case-based learning (customised) Problem-based and project based learning Coaching Highly customised applying theory and concepts within the company context 3-5 Managers able to impact on business change within the organisation High – material is highly customised Continued support for delegates and access to academics and institutional facilities High for both company and institution Complex cost structure and legal structuring Part of a wider portfolio of services Senior supply chain High intimacy across the full academic team Deep collaboration and intimacy with client company – Co- development of material and high number of design iterations High level of interfaces between multiple actors in the institution and company Strategic support programmes The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 customised to have relevance within the company context. Strategic support programmes include a higher degree of workshops and discussion sessions focussing on the implications for theory and the business strategy and facilitators and barriers to change management within the organisation. This is in line with the presence of a transformational agenda in customised programmes discussed by Kets de Vries and Korotov (2007). The theoretical input, combined with the opportunity to discuss and interact with peers give participants the space and time to both reflect and conceptualise (Kolb, 1984, 1993), allowing them to learn from their experiences. The inclusion of company based information and case examples takes significant time to generate. The analysis of timetables showed that a number of company specific cases were presented by company experts. These cases give participants an initial opportunity for active experimentation, closing Kolb’s (1984, 1993) learning cycle. For one programme this was nearly 30 per cent of the total class time. From the academic course director’s perspective, the benefit was the first hand experience offered by the external presenters, however assuring the consistency and quality of these sessions was often problematic. The nature of post-course delegate work varied but where it was a major component of the programme, significant planning was required to ensure the project work was managed. This included, defining the projects in advance of the programme, assigning delegates to appropriate projects with sufficient skill sets, providing access to online information and learning systems, and interim and final presentation feedback days. This level of post-course involvement is consistent with the recommendations of Carter et al. (2006) in terms of measurement of deliverables and monitoring of results. Furthermore, these projects allow participants another opportunity for active experimentation (Kolb, 1984, 1993) in order to consolidate the learning cycle. These changes also have important implications for faculty. For Strategic support programmes the traditional lecture is less relevant, and skills like facilitation and coaching are much more important. As one of the interviewees has put it: For practitioners it provides evidence documenting the changing requirements of supply chain executive education. The framework shows how educational programmes can support a transformational agenda and provides guidance that can help commission, design and manage executive education programmes. For academics the framework can help to evaluate the changes affecting customised executive education in SCM, to design and deliver programmes for clients requiring customised programmes, and to articulate the relationship with existing and prospective clients. The framework also contributes to the educational literature by highlighting the changing educational needs in specialist subjects, such as, SCM; trends that might affect other domains. The evolution towards strategic support programmes also present challenges for SCM academics, because it calls for greater understanding and better engagement with industry. Furthermore it requires academics to accept that at least some of the “students” might be subject experts in their own right. Hence, academics not only need to have command of their subject matter, but also have the humility to learn from course participants. Ultimately this two-way learning process is likely to benefit both academics and practitioners. The research design aimed to mitigate the limitations of both methods used in terms of reliability and internal as well as external validity. Despite the efforts of the authors, the work still suffers from limitations which could be overcome through further research. For instance, a wider evaluation of trends in different industries and different regions could help to understand if the trends identified here are applicable in other countries and other institutions. The authors propose undertaking a quantitative survey of customers and providers to validate and further develop the framework. They also propose further exploration of the relationships between academic institutions and customers of executive education. This could lead to a better understanding of the types of customer-supplier relationships operating in this arena and the factors that affect the success of these relationships. This would benefit both customers and suppliers of executive education. Faculty who believe they are the sole repository of knowledge are seriously deluded. Now we have to help practitioners execute on knowledge and promote their curiosity. We have to be experts on the process of learning as well as on the subject matter. References Beaty, L. (2003), “Supporting learning from experience”, in Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshal, S. (Eds), A Handbook for Teaching & Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice, 2nd ed., Routledge-Falmer, London, pp. 134-147. Birou, L., Croom, S. and Lutz, H. (2008), Global Benchmarking Study SCM Syllabi: Topics, Reading Assignments, Assignments and Course Requirements, DSI, November. Bruner, J.S. (1960), The Process of Education, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Bruner, J.S. (1966), Towards a Theory of Instruction, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA. Bryman, A. and Bell, E. (2007), Business Research Methods, Oxford University Press, Oxford. Büchel, B. and Antunes, D. (2007), “Reflections of executive education: the user and provider’s perspective”, Academy of Conclusions and future research directions Based on the empirical results, this paper makes two contributions. First, it contributes to the extant literature by bridging the gap in exploring the evolving nature of executive education programmes. It presents a conceptual framework documenting the relational form, andragogical education and programme design for three different types of programmes: 1 knowledge gap; 2 specialist/technical; and 3 strategic support. Second, it uses the framework to explore the implications for practitioner and for providers of executive education. 452 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 Management Learning and Education, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 401-411. Carter, J., Closs, D.J., Dischinger, J.S., Grenoble, W.L. and Maxon, V.L. (2006), “Executive education’s role in our supply chain future”, Supply Chain Management Review, September. Christopher, M. (2010), Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 4th ed., Financial Times/Prentice Hall, Harlow. Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe\, R. and Lowe, A. (2001), Management Research: An Introduction, 2nd ed., Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA. Freeman, V.T. and Cavinato, J.L. (1992), “Fostering strategic change in a function through executive education: the case of purchasing”, Journal of Management Development, Vol. 11 No. 6, pp. 25-30. Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshal, S. (2003), “Understanding student learning”, in Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshal, S. (Eds), A Handbook for Teaching & Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice, 2nd ed., RoutledgeFalmer, London and New York, NY, pp. 9-25. Gammelgaard, B. and Larson, P.D. (2001), “Logistics skills and competencies for supply chain management”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 27-50. Garvin, D.A. (2007), “Teaching executives and teaching MBAs: reflections on the case method”, Academy of Management Learning and Education, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 364-374. Giuinipero, L.C. and Handfield, R.B. (2004), Purchasing Education and Training II, CAPS, Research Report, Tempe Arizona. Giunipero, L., Handfield, R.B. and Eltantawy, R. (2006), “Supply management’s evolution: key skill sets for the supply manager of the future”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 26 No. 7, pp. 822-844. Glaser, B.G. and Strauss, A.L. (1967), The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research, Aldine Publishing Company, Chicago, IL. Gravier, M.J. and Farris, M.T. (2008), “An analysis of logistics pedagogical literature: past and future trends in curriculum, content, and pedagogy”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 233-253. Honey, P. and Mumford, A. (1982), The Manual of Learning Styles, Peter Honey, Maidenhead. Johnson, M.E. and Pyke, D.F. (2000), “A framework for teaching supply chain management”, Production and Operations Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 2-18. Johnson, R.B. and Onwuegbuzie, A.J. (2004), “Mixed methods research: a research paradigm whose time has come”, Educational Researcher, Vol. 33 No. 7, pp. 14-26. Kets de Vries, M.F.R. and Korotov, K. (2007), “Creating transformation executive education programs”, Academy of Management, Learning & Development, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 375-387. Knowles, M.S. (1974), “Human resources development in OD”, Organization Development, March/April, pp. 115-124. Knowles, M.S. (1979), “Speaking from experience: the professional organization as a learning community”, Training and Development Journal, May, pp. 36-42. Knowles, M.S. (1980), “How do you get people to be selfdirected learners?”, Training and Development Journal, May, pp. 96-101. Knowles, M.S. (1984), Andragogy in Action: Applying Modern Principles of Adult Learning, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, CA. Kolb, D.A. (1984), Experimental Learning, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Kolb, D.A. (1993), “The process of experiential learning”, in Thorpe, M., Edwards, R. and Hanson, A. (Eds), Culture and Processes of Adult Learning, Routledge/OUP, London, pp. 138-155. Lancioni, R., Forman, H. and Smith, M.F. (2001), “Logistics and supply chain education: roadblocks and challenges”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 31 No. 10, pp. 733-745. Larson, P.D. and Halldorsson, A. (2004), “Logistics versus supply chain management: an international survey”, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, Vol. 7 No. 1, pp. 17-31. Leonard-Barton, D. (1990), “A dual methodology for case studies: synergistic use of longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites”, Organization Science, Vol. 1 No. 3, pp. 248-266. McKevitt, D., Davis, P., Woldring, R., Smith, K., Flynn, A. and McEvoy, E. (2012), “An exploration of management competencies in public sector procurement”, Journal of Public Procurement, Vol. 12 No. 3, pp. 333-355. Mangan, J. and Christopher, M. (2005), “Management development and the supply chain manager of the future”, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 178-191. Meredith, J. (1998), “Building operations management theory through case and field research”, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 1 No. 6, pp. 441-454. Morton, F. and Booth, S. (1997), Learning Awareness, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ. Myers, M.B., Griffith, D.A., Daugherty, P.J. and Lusch, R.F. (2004), “Maximizing the human capital equation in logistics: education, experience, and skills”, Journal of Business Logistics, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 211-232. Newman, W.H. and Stoner, J.A.F. (1989), “Better vision for old dogs: teaching experienced managers”, Proceedings of the 1989 Annual Academy of Management Meeting, pp. 132-136. Oppenheim, N.A. (2001), Questionnaire Design, Interviewing and Attitude Measurement, Continuum, London. Piaget, J. (1950), The Psychology of Intelligence, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. Rock Kopczak, L. and Fransoo, J.C. (2000), “Teaching supply chain management through global projects with global project teams”, Production and Operations Management, Vol. 9 No. 1, pp. 91-104. Supply Chain Council (2010), Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) Model – Overview – Version 10.0, available at: http://supply-chain.org/f/SCOR-OverviewWeb.pdf (accessed 19 July 2012). Tushman, M.L., O’Reilly, C.A., Fenollosa, A., Kleinbaum, A.M. and McGrath, D. (2007), “Relevance and rigor: executive education as a lever in shaping practice and research”, Academy of Management Learning & Education, Vol. 6 No. 3, pp. 345-362. van Hoek, R., Chatham, R. and Wilding, R. (2002), “Managers in supply chain management, the critical 453 The evolution of customised executive education in SCM Supply Chain Management: An International Journal Mike Bernon and Carlos Mena Volume 18 · Number 4 · 2013 · 440 –454 dimension”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 7 No. 3, pp. 119-125. van Hoek, R., Godsell, J. and Harrison, A. (2011), “Embedding ‘insights from industry’ in supply chain programmes: the role of guest lecturers”, Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, Vol. 16 No. 2, pp. 142-147. Voss, C., Tsikriktsis, N. and Frohlich, M. (2002), “Case research in operations management”, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 22 No. 2, pp. 195-219. Wu, Y.J. (2007), “Contemporary logistics education: an international perspective”, International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, Vol. 37 No. 7, pp. 504-528. Yin, R.K. (2008), Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed., Sage Publications, New York, NY. management development programmes as well as directly supporting the development of individual senior company personnel. Apart from lecturing on postgraduate courses at Cranfield, Mike regularly teaches at academic institutions across Europe and Asia. As a supply chain specialist, Mike also engages in consultancy projects with organisations across a broad spectrum of industries. Carlos Mena is Director of the Centre for Strategic Procurement and Supply Management and head of the Executive Procurement Network (EPN). The EPN is a joint initiative with the Chartered Institute of Purchasing and Supply (CIPS) to develop a vibrant network of procurement professionals engaged in a collaborative effort to create and disseminate thought leadership in the field of procurement. Carlos has been responsible for more than ten research projects in supply chain-related fields such as global sourcing, sustainable supply chains and collaboration. In these projects, he has collaborated with world-leading organisations such as ASDA (Wal-Mart), British Airways, Coca-Cola, Ford, M&S, Tata, Tesco and P&G. He regularly presents at international conferences and lectures in a variety of subjects including procurement, supply chain management, lean manufacturing, operations strategy and sustainability. Carlos received his doctorate degree (EngD) from the University of Warwick, as well as an MSc in Engineering Business Management. He also holds a BEng in Industrial Engineering from the Iberoamericana University in Mexico. Carlos Mena is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: carlos.mena@cranfield.ac.uk Further Reading Biggs, J. (1987), Student Approaches to Learning and Studying, Australian Council for Education and Research, Hawthorn, Victoria. About the authors Mike Bernon is Executive Development Director - Supply Chain and Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Cranfield School of Management. As Executive Development Director, Mike works with global companies to design and develop senior To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints 454