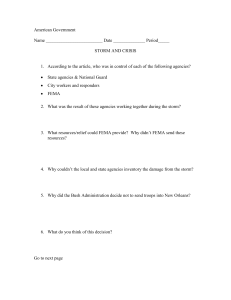

Understanding the Consequences of Hurricane Katrina for ACF Service Populations:

advertisement