HOUSING DEMAND AMONG PANAMA’S MIDDLE- AND LOW-INCOME POPULATION Prepared by

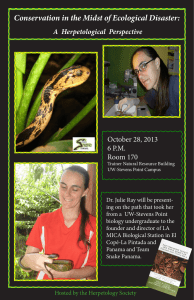

advertisement