States, Citizens, and Local Performance Management Pat Dusenbury

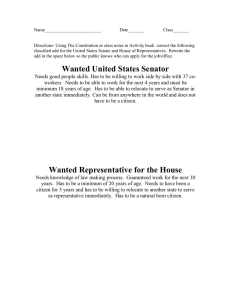

advertisement