i THE SYNTACTIC DIFFICULTY OF RELATIVE CLAUSES FOR KOREAN STUDENTS:

advertisement

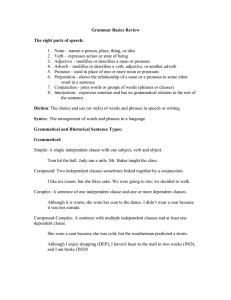

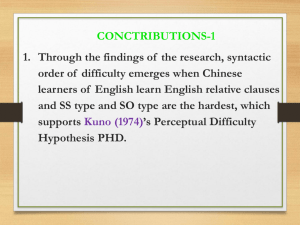

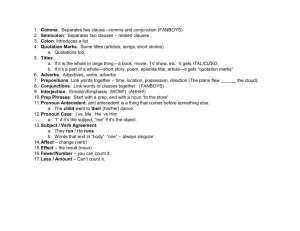

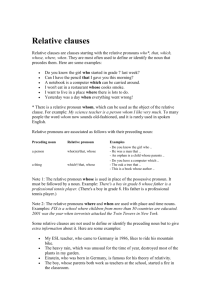

i THE SYNTACTIC DIFFICULTY OF RELATIVE CLAUSES FOR KOREAN STUDENTS: AN ANALYSIS OF ERRORS AND AVOIDANCE STRATEGIES by Chanyoung Park An Applied Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Teaching English as a Second Language ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY DECEMBER 2000 THE SYNTACTIC DIFFICULTY OF RELATIVE CLAUSES FOR KOREAN STUDENTS: AN ANALYSIS OF ERRORS AND AVOIDANCE STRATEGIES by Chanyoung Park ii has been approved December 2000 APPROVED: _________________________________________________________________, Chair ______________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________ Supervisory Committee ACCEPTED: __________________________________ Department Chair __________________________________ Dean, Graduate College iii ABSTRACT This paper reports on the syntactic difficulty order of relative clauses (RCs), and analyzes the errors and avoidance strategies used by 10 Korean learners of English. Three hypotheses from previous studies are examined in the present study, that is, the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis (PDH), Noun Phrase Accessibility Hypothesis (NPAH), and Parallel Function Hypothesis (PFH), which indicate the difficulty of center embedding, pronoun fronting, and non-parallel function, respectively. A one-page questionnaire, which contains 12 sets of sentence combining tasks, was constructed and used. The questionnaire was designed to force the students to write each 3 of 4 different types of RCs: OS, OO, SS, SO types ( O for Object and S for subject). The first symbol shows the function of the noun phrase (NP) in the main clause, and the second, that of the relativized clause. The present study supports NPAH and PDH, but not PFH. The data show the order of usage as SS/SO, OS, and OO from the greatest to the least. Many errors were made in SS and SO types; this indicates the difficulty of center embedding and thus supports the PDH. A novel finding of this paper is that L1 transfer influences the perceptual difficulty of RC, and is shown in access and avoidance strategies. Another contribution of this paper is the introduction of a 4-step teaching method for RCs. iv ABBREVIATIONS The following abbreviations are used to label the linguistic terms employed in this volume. * Ungrammatical (when placed before an example) AdjP Adjective Phrase C Complementizer D Determiner ESL English as a Second Language EFL English as a Foreign Language L1 First language L2 Second language NP Noun Phrase NPAH Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis (NPAHH) PDH Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis PFH Parallel Function Hypothesis RC Relative Clauses V Verb VP Verb Phrase v TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ……………………………………………………………………… i ……………………………………………………………… ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ………………………………………………………….. iii ……………………………………………… 1 CHAPTER 2: RELATIVE CLAUSES ……………………………………………. 4 2.1. Definition and the Structure …………………………………………… 4 2.2. Different Types of Relative Pronouns and Relative Clauses ………….. 6 2.2.1. The Relativization of the Subject ………………………………... 6 2.2.1.1. Subject-subject Relatives ………………………………. 6 2.2.1.2. Object-subject Relatives ……………………………….. 7 ABBREVIATIONS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 2.2.2. The Relativization of the Object ……………………..…………… 8 2.2.2.1. Subject-object Relatives ………………………………… 8 2.2.2.2. Object-object Relatives ………………………………….. 8 2.2.3. Relativization of the Possessive ………………………………….. 9 2.3. Relative Pronoun Deletion Rules ………………………………………… 10 CHAPTER 3: STUDIES IN THE ACQUISITION OF RELATIVE CLAUSES …….. 12 3.1. The Complexity of Relative Clauses …………………………………….. 12 3.2. The Order of Difficulty and Three Hypotheses on the Difficulty of Relative Clauses …………………………………………………………………… 13 3.3. Native Language Transfer ……………………………………………….. 17 vi 3.4. Corpus-Based Approach ………………………………………………… 18 CHAPTER 4: HYPOTHESES AND METHODS …………………………………... 20 4.1. Research questions ………………………………………………………. 21 4.2. Hypotheses ………………………………………………………………. 21 4.3. Methodology …………………………………………………………….. 22 4.3.1. Subjects ……………………………………………………………. 22 4.3.2. Materials …………………………………………………………… 23 4.3.3. Procedure …………………………………………………………... 24 CHAPTER 5: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ……………………………………… 25 5.1. The Order of Difficulty …………………………………………………... 25 5.2. Data Analysis …………………………………………………………….. 27 5.2.1. Error Analysis ……………………………………………………… 28 5.2.1.1. Error Type 1. Pronoun Retention …………………………….. 29 5.2.1.2. Error Type 2. Relative Clause Marker Selection …………….. 29 5.2.1.3. Error Type 3. Adjacency ……………………………………... 30 5.2.1.4. Error Type 4. Be-verb Omission ……………………………... 31 5.2.1.5. Error Type 5. Misplacing or Omitting Subject in Objective RCs.31 5.2.1.6. Error Type 6. Modifying Wrong Antecedent ………………… 32 5.2.2. Avoidance Strategy Analysis ………………………………………. 33 5.3. Discussion ………………………………………………………………... 36 CHAPTER 6: TEACHING SUGGESTIONS AND CONCLUSION ……………….. 40 6.1. Conclusion ……………………………………………………………….. 40 6.2. Teaching Suggestions: 4 steps …………………………………………… 41 vii 6.3. Implicit Activities …………………………………………………….…. 43 REFERENCES …………………………………………………………………….… 46 APPENDIX …………………………………………………………………………... 48 viii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION From my own experience of learning English as a foreign language, I remember that a friend of mine one day came to me, pointing to another person, and said “She must be very good at English. She even uses relative clauses when she talks in English.” Relative clauses (RCs) have been considered as the symbol of complex English structure and even some extent, the indicator of mastery in English. The reason can be found in the process of producing RCs. In order to acquire relative clauses, students have to learn the identification of identical NPs, relative pronoun substitution, word order rearrangement, and the process of embedding. In addition, English is syntactically very different from Korean. Korean is an SOV language, while English is an SVO language. Korean RCs are prenominal modifiers, but English RCs are post-nominal modifiers. Korean has an invariable relative pronoun, whereas, English has variable relative pronouns. Schachter (1974) and Gass (1980) explored acquisition of relative clauses in the perspective of native language transfer. Chiang (1980)’s replication of Schachter’s study reports that overall target language proficiency is the best predictor of relative clauses production. Several SLA researchers have studied on the order of natural difficulty among four types of relative clauses, that is, SS, SO, OS, and OO. The first letter stands for the function of the head noun in the main clause and the second letter stands for the function of the relative pronoun of the relative clause. Kuno (1975) argued that center embedding is perceptually more difficult and therefore, OS/ OO clauses are easier than SS/ SO ix clauses. On the other hand, Keenan (1975), in his noun phrase accessibility hierarchy, focused on embedded relative clauses rather than the main sentences. He hypothesized that relativized subjects are more accessible than relativized objects, which means SS/ OS types are easier than SO/ OO types. The hierarchy is as follows, from most “accessible” to the least “accessible”: subject NP, direct object NP, indirect object NP, oblique object NP, genitive object NP, and object NP of a comparison. Ioup and Kruse (1977)’s data supported Kuno’s study and a later study by Schumann (1980) also supported Kuno’s hypothesis. The present study questions an assumption in Schumann’s study, namely that the more frequently produced type is the easiest form. It is plausible that easier structures are used more often because his subjects were non-native speakers of English. However, there can be a variable that subjects produced OS, OO more often, just because those are occurring more frequently in a daily conversation. Stauble (1978)’s research provided the same frequency of these four types of relative clauses with native English speaker subjects; this weakens the logic of Schumann’s study, which assummed that if one type of RC is used more often, it can be considered as easier . However, certain types of RCs can be used more often by the nonnative speakers just because they are more often used in a real language. Therefore, in this study, errors and avoidance rate were also considered to in measuring the difficulty of each relative clauses type in addition to the frequency of production. In this paper, I investigate the syntactic difficulty that lies in the formation of relative clauses and I analyze the errors and avoidance strategies of 10 Korean learners of x English. The methodology used was a questionnaire with 12 sets of combining sentence tasks, which force the subjects to write 3 of 4 different types of RCs. Chapter 2 contains a general description of relative clauses, including definitions and different types of relative clauses. Chapter 3 reviews the theories and studies regarding L2 acquisition of relative clauses. It discusses three different hypotheses on the difficulty of relative clauses. The Parallel Function Hypothesis, the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis, and the Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis. It also includes the studies from the perspective of native language transfer, and corpus-based approach. Chapter 4 explains the research questions, hypothesis, and methodology of data collection, the subjects and the procedure. Chapter 5 investigates the result obtained by the questionnaire. It also provides an error analysis and an avoidance strategy analysis. Chapter 6 draws the conclusion from the study and gives some teaching suggestions. xi CHAPTER 2. 2.1. RELATIVE CLAUSES Definition and Structure Clauses that function inside the phrase as modifiers are called relative clauses (RCs). For example, the clause in brackets, who crossed Antarctica in (1), is a relative clause. (1) The man [who crossed Antarctica] was happy. English relative clauses are introduced by a relative pronoun and modify their NP antecedents or head noun. In (1), man is the antecedent that is modified by the RC in brackets. The relative pronoun who indicates or replaces the antecedent man and also serves as a complementizer. The relative clause always contains a gap t, which is indicated by the trace of the relative pronoun as in (2). (2) S NP VP S’ NP D N C V S NP t The man who AdjP VP V crossed NP Antarctica was happy. The basic structural relationship in RCs is formed by a process called embedding, which is the generation of one clause within another higher-order or superordinate clause such that the embedded clause becomes a part of the superordinate main clause. For example: xii (3) The fans [who were attending the rock concert] had to wait in line for three hours. (NP[S] ) a. The fans had to wait in line for three hours. b. The fans were attending the rock concert. (Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999, p572) Originally, sentence (3) is derived from (3a) and (3b). (3a) is a main clause and (3b) was embedded in (3a). The fans is the noun that occurs in both sentences. When embedded, this noun will be substituted by the relative pronoun, which is who in the sentence (3). In this process, the relative pronoun will take the same case as the original embedded sentence. In other words, the fans in the second clause, (3b) is the nominative case, therefore, it will be replaced by the nominative relative pronoun, who. In the main sentence, the fans will be an antecedent that will be modified by the relative clause. There are four processes in producing RCs. First, the identical NP or modified antecedent should be identified. Second, proper relative pronoun should be chosen and substitute the identical NP in the relativized clause. Third, relative pronoun should be fronted when the function of the identical NP is an object in the relativized clause. Fourth, the relativized clause should be placed after the modified antecedent. This process, as I mentioned above, is called embedding. When the relative clause modifies the subject of the main clause, the relative clause is embedded in the middle of the main clause; this is called center embedding. Identifying identical NPs, relative pronoun substitution, and embedding applies to all types of relative clauses. On the other hand, relative pronoun fronting and center xiii embedding applies to certain types. The following section introduces the different types of relative clauses and explains the process involved in each types. 2.2. Different Types of Relative Pronouns and Relative Clauses Relative clause structures can be broadly categorized in terms of function of the head noun in the main clause and of the function of the identical noun in the relative clause. In the main clause, head nouns can function as subject, direct object, indirect object, object of the preposition, or predicate noun. In the relative clause, heads of the NP can function as subject, direct object, indirect object, or object of a preposition. Moreover, the possessive determiner whose can relativize any noun functioning as a subject, direct object, object of a preposition, or predicate noun. I will go into these in the following sections. 2.2.1. The Relativization of the Subject 2.2.1.1. Subject-subject Relatives (SS type) When the subject of the embedded sentence is relativized, it will be replaced by a nominative relative pronoun, who, which, or that. Consider the following sentence: (4) The man who speaks Korean is my brother. This sentence is formed through embedding The man speaks Korean into The man is my brother. Who is the relative pronoun that can be used to refer to persons of either gender in singular or plural. In this sentence, who replaces the man. The man in the embedded sentence functions as subject, and the man in the main clauses also functions as subject. In order to function as a relative clause, the embedded clause must contain an NP that is xiv identical in form and reference to the NP in the main clause. In the above example, NP is the man which refers to the same thing in both sentences and it is in identical form. The relative clause is functioning as an adjective, modifying the noun preceding it. The relative pronoun which replaces a non-human thing, and that replaces both which and who. The processes involved in the producing of SS type RCs are relative pronoun substitution and center embedding. 2.2.1.2. Object-subject Relatives (OS type) The subject of the sentence can be relativized and embedded into the main clause modifying the object of the main clause. In this case also, the identical NP, subject of the embedded sentence and the object of the main sentence, is needed. For example: (5) I know the man who speaks Korean. This sentence is composed of two base sentences. I know the man and The man speaks Korean. In the former sentence, which is the main sentence, the man is the object. And in the latter sentence, the man is a subject. A relative pronoun is replacing the subject of the embedded sentence; therefore, it adopts subject case. In the above, sentence, the man was the direct object of the sentence. Indirect objects and the object of the main sentence can be modified by the subject relative clauses as well. The process involved in OS type of RCs is relative pronoun substitution. xv 2.2.2. The Relativization of the Object 2.2.2.1. Subject-object relatives (SO type) In this type of relative clause, the object NP of the embedded sentence will be relativized to modify the subject of the main sentence. For example: (6) The girl whom you met is my sister. In this sentence, You met the girl is embedded into The girl is my sister. The girl is an object in the embedded sentence and the subject of the main sentence. Since the object of the embedded sentence is relativized, it will take the relative pronoun with the objective case, as whom in the above sentence. The objective relative pronouns are who, whom, which, and that. The relative pronoun who is used for both nominative and accusative cases, and whom is used for formal accusative cases and after prepositions. The two identical NPs are not adjacent as they were in the two previous sentences discussed above. Therefore, after replacing the object with the relative pronoun, the relative pronoun has to move to the front of the relative clause to be adjacent to the noun modified. This rule is referred to as “relative pronoun fronting” (Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman, 1999, p576). The processes involved in SO type of RCs are relative pronoun substitution and relative pronoun fronting. 2.2.2.2. Object-object relatives (OO type) In this type of relative clauses, the object of the embedded sentence will be relativized to modify the object of the main sentence. For example: (7) I read the book that you wrote. xvi The base sentences are I read the book and you wrote the book. The book is the identical NP in both sentences. In the embedded sentence, the book is replaced by the relative pronoun that, which takes the object case of the original sentence. In summary, the process of identical NP identification, relative pronoun substitution, and embedding applies to every type of RC. Objective relative clauses, such as SO and OO types, require relative pronoun fronting. When the subject of the main sentence is an antecedent such as SS and SO types, center embedding is required (see table1). When a target language construction has several processes involved, it is more complicated and more difficult for second language learners than simple structures. Therefore, from the table 1, we can infer that SO type may be the hardest and OS type may be the easiest. Table 1. The Process in Each Type of RC. Identical NP identification Relative pronoun substitution Embedding Relative pronoun fronting Center embedding Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No Yes No Yes Yes Yes No No SS SO OS OO 2.2.3. The Relativization of the possessive In sentence (8), whose replaces his in (8-b). Whose generally refers to human head noun but sometimes it refers to inanimate noun too as in (9). (8) I met the man whose name is John. a. I met the man. xvii b. (9) His name is John. I found an old coin whose date has become worn and illegible. Table 2. Relative Pronoun HUMAN NON-HUMAN SUBJECTIVE Who That which that OBJECTIVE Whom Who That which Whose whose POSSESSIVE that Table 2 shows a summary of the types of relative pronouns. Subjective relative pronouns are who, which, and that. Who is used for indicating humans and which for nonhumans. That can be used for both. Objective relative pronouns are who, whom, which, and that. Who, whom, and that are used for humans, and which and that for non-humans. Who is used as both subjective and objective. Whom is more formal and used mostly after prepositions. The possessive relative pronoun is whose and can be used for both human and non-human antecedents. 2.3. Relative Pronoun Deletion Rules A relative pronoun in a relativized object can be deleted unless it follows a preposition, which is fronted with the pronoun. The relative pronoun +be verb deletion rule applies when a restrictive relative clause containing 1) a relativized subject and a verb in the progressive aspect , 2) a relativized subject and a verb in the passive voice, xviii and 3) a relativized subject followed by the be copula and a complex adjective phrase. Following is the example of each cases: (10) I saw a man (who was) crossing the street. (11) I like cookies (which are) made by mom. (12) I stayed in a hotel (which is) the most luxurious in the world. xix CHAPTER 3. STUDIES IN THE ACQUISITION OF RELATIVE CLAUSES 3.1. The Complexity of Relative Clauses Relative clauses are considered as complex postnominal modifiers in English. Therefore, they appear in the latter part of second-language English textbooks, and are taught at an intermediate level in an English class. For example, the Grammar Book (Azar, 1995), which is used for beginning classes at the American English and Culture Program, the language institute in Arizona State University, doesn’t include relative clauses at all. Doughty (1990) also shows that English relativization is learned or acquired relatively late for L2 students. This indicates the syntactic complexity of the relative clauses. In her study, among six levels in an intensive English institute in Philadelphia, the highest levels had already acquired considerable knowledge of relativization while the lowest level of students couldn’t understand the grammaticality judgment task at all. Relativization ability begins to appear in the middle proficiency level of students. Chiang (1980) also shows that overall language proficiency is the first predictor of the production of the relative clauses. His study is a replication of Schachter (1974)’s study which found that Chinese and Japanese students committed significantly fewer errors in using English relative clauses in an English composition task than did Persian and Arab students. However, Schachter also found that the relative clauses used by Persian and Arab students were more complex than the ones used by Japanese and Chinese students. Even in the total number, Persian and Arab students produced more. xx Chiang found that the language background also affects the use of relative clauses; however, overall language proficiency was the major factor that affects the production of RCs. 3.2. The Order of Difficulty and Three hypotheses on the difficulty of relative clauses As Doughty (1990) emphasized, finding the universal orderings is crucially important to the enhancement of instructed interlanguage (IL) development because such knowledge can be used to decide the sequencing and timing of instruction. Studies have been done to find the order of difficulty among four types of relative clauses, that is, subject-subject(SS), object-subject(OS), subject-object(SO), and objectobject(OO) relative clauses. Among studies of ordering the difficulty of relative clauses, three hypotheses explain the respective universal factors that affect the acquisition of relative clauses: the Parallel Function Hypothesis, the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis, and the Noun Phrase Accessibility Hypothesis. The Parallel Function Hypothesis (hence PFH, Sheldon, 1974) focuses on both functions of the head noun in the main sentence and the relative pronoun. The PFH assumes that if two functions are same, it is easier to produce. That is to say, subjectsubject (SS) and object-object (OO) sentences are easier than subject-object (SO) and object-subject (OS) sentences. PFH was formulated originally to account for first language relativization. Sheldon (1977) investigated four to five year old English speaking children, on their ability to comprehend sentences with above four types of relative clauses. He found that the subjects showed the average of over 50% of correctness in SS and OO type xxi sentences, whereas less than 30% correctness in SO and OS type of sentences; this shows the simplicity of SS and OO types. The Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis (PDH) deals with the universal factor of interruption. Kuno (1974) assumed that center embedding would interrupt the flow of the main sentence and would be the most difficult kind of embedding. The main sentence is interrupted by the embedded relative clause when it modifies the subject, and comes directly after the subject of the main clause. Therefore, he hypothesized that OS and OO types would be easier for the learners to acquire than SS and SO types in English because they modify the object of the main clause that comes at the end of the main sentence, and the relative clause follows right after that without interrupting the main sentence. For example, in the sentence (13), we can see that there is no interruption at all. Only the subject of the embedded sentence was substituted by who. Moreover, nothing moved in the embedded sentence. (13) I know the man who speaks English. a. I know the man. (object) b. The man speaks English. (subject) Sentence (14) is an example of an OO relative clause. The embedded sentence does not interrupt the main sentence; however, the place of the object of the embedded sentence should move to the front to be adjacent to the antecedent, the cake. Because of the object movement, OO is less simple than OS. (14) I ate the cake which you made. a. I ate the cake. (object) b. You made the cake. (object) xxii Ioup and Kruse (1977) supported Kuno’s hypothesis and later study by Schumann (1980) also seems to support Kuno’s Hypothesis. Schumann examined the data from seven ESL learners and found the order of OS, OO, SS, SO relative clauses in the frequency of their use. This supports the PDH and is against PFH. In a subsequent study by Wong (1991) done with 170 Cantonese speakers, the same acquisition order was found. Stauble (1978, in Celce-Murcia & Larsen-Freeman, 1999) examined the frequency of these relative clauses among native speakers and found the same order. The data was drawn from different discourse types: informal speech, spontaneous writing, and published writing. There is correlation between the rank order and frequency of occurrence of the different types of relative clauses used by native speakers and second language acquisition order. It allows for the possibility that Schumann’s study is the reflection of the occurring frequency of the usage of RCs in real life, rather than the reflection of the difficulty orders; this weakens the logic of Schumann’s study, which claimed the correlation of frequency of production and simplicity. The final hypothesis is the Accessibility Hypothesis, or Noun Phrase Accessibility Hypothesis (NPAH), proposed by Keenan and Comrie in 1972. This hypothesis is different from the two previously mentioned hypotheses in that it focuses only on the relativized clauses and the functions of the relative pronouns inside these clauses (described in detailed six categories). The following lists their most “accessible” type of NP at the top and the least accessible type at the bottom: Subject NP (most accessible or most able to become a relative pronoun) Direct object NP xxiii Indirect object NP Oblique object NP (i.e., object of a preposition that is not an indirect object) Genitive (i.e., possessive) NP Object NP of a comparison (least accessible or least able to become a relative pronoun) For this hypothesis, Keenan and Comrie analyzed many languages and aimed to find elements of universality. For example, Tagalog can relativize only subjects. On the other hand, Slovenian can relativize object NPs of comparisons, which implies that it can also relativize all the other five types of NPs that are higher in hierarchy. If it is more universal it is less marked, according to markedness theory, therefore, more accessibility can be validly interpreted as easier form. Sadighi (1994) examined the comprehension of English restrictive relative clauses containing three universal factors mentioned above: interruption, word order rearrangement, and parallel function. His subjects were Chinese (24), Japanese (20), and Korean (12) adult native speakers (n=56). His study concentrated on the comprehension of these English RC structures. The purpose of his study was to probe the relative difficulty of comprehension of the various types of English Restrictive RCs among the Chinese, Japanese, and Korean speakers, whose native languages have pre-nominal relativization, and find whether the results are the same with the native speakers of English (L1 learners) and Arabic and Farsi (L2 learners), whose native languages have post-nominal relativization. Sadighi’s results show an order of difficulty from easy to hard: OS, SO, OO, SS. The results of his study confirm the dominance of language universals in the course of xxiv language acquisition regardless of particular languages’ specificities. It shows the influence of the influence of the two factors, interruption and word-order rearrangement, but not the Parallel Function. 3.3. Native Language Transfer One way to explain the learner’s interlanguage is through language transfer, which means the effect of L1 in the acquisition of L2. Studies by Gass (1980), Chiang (1980), and Schachter (1974) were conducted on the acquisition of relative clauses from the perspective of native language transfer or Contrastive Analysis. Gass (1980) shows the transfer of resumptive pronouns, in other words, pronoun retention or pronominal reflexes. She studied the acquisition of English relative clauses by 17 adult speakers of typologically diverse language backgrounds. A grammaticality judgment task and a combining task were used to examine L1 transfer. Gass’s study reports transfer in pronoun retention. Especially in the three highest positions on the NPAH, that is, subject NP, direct object NP, and indirect object NP positions, the speakers of the languages that have pronoun retention had the tendency to choose the sentence with pronoun retention to be correct. Schachtler (1974) investigated the structure of English relative of adult learners of English from Farsi, Arabic, Chinese, and Japanese L1 backgrounds. In their free composition, Persian and Arab students produced significantly more errors in relative clauses than Chinese and Japanese students, and the total number of RCs produced by Persian and Arab students was higher than that of Chinese and Japanese students, which shows the influence of the native language transfer. Farsi and Arabic have postnominal xxv relative clauses, while Japanese and Chinese have prenominal relative clauses, therefore, Persian and Arab students find English RCs so similar to their native languages and they assume that they can dirctly transfer their native language forms to English, and they make numerous errors in pronominalization since Persian and Arab has pronominal reflexes. Meanwhile, Chinese and Japanese students avoid using relative clauses and they produce RCs when they are relatively sure that they are correct. Chiang’s (1980) study replicated Schachter’s (1974) study and investigated the relationship between frequency of relative clause production and first language. Chiang found that the role of L1 in acquisition of English relative clauses is less significant than the overall language proficiency in predicting RC use. 3.4. Corpus-based Approaches Biber, Conrad and Reppen (1994), in their corpus-based study, examined the frequency of different types of postnominal modifier used in three registers: editorials, fiction, and letters. They also reviewed several ESL grammar books and counted the number of pages devoted to three types of postnominal modifiers, and contrasted the actual patterns in use and attention received in teaching. Biber, et al. found out that relative clauses are clearly regarded as a central construction and receive extensive discussion among post-nominal modifications; meanwhile, prepositional phrases as post-nominal modifiers receive the least attention in teaching. For example, in four grammar books reviewed, 10 to 22 pages were allotted to relative clauses, whereas, only 1 to 3 pages were used for prepositional phrases and participial phrases as noun modifiers. However, the actual patterns of use in three written xxvi registers are quite different from the emphases in these pedagogical grammars. Prepositional phrases as noun modifiers are far more common than either of these other constructions. Fiction and letters show similar patterns, and their overall frequency of postnominal modifiers is much lower than in editorials. There are few relative clauses or participial clauses in fiction, and almost none of these features occur in personal letters. In contrast, there are moderate but notable numbers of prepositional phrases as postnominal modifiers in both fiction and letters. In conclusion, the PFH, which claims that a sentence is easier when the NP in the main clause and the relative pronoun have the same functions, predicts the following order of difficulty: SS/OO >SO/OS (left of > indicates the easier one). The PDH, which attributes the difficulty to center embedding, predicts that the order of difficulty is OS/OO >SS/SO types. The NPAH, which discovered the universal order of accessibility among all languages, says the hierarchy is Subject NP>Direct object NP>Indirect Object NP>Oblique Object NP> Genitive NP> Object NP of comparison. Schumann’s study says the order is OS >OO >SS >SO types. From the perspective of the process involved in each type, mentioned in chapter 2, the order of difficulty is SO > SS/OO > OS. xxvii CHAPTER 4. 4.1. HYPOTHESES AND METHODS Research Questions This paper is designed to answer the following research questions. 1. Is there any difference in syntactic difficulty among different types of relative clauses, in relation to the function of the antecedent and the relative pronoun in main clauses and embedded clauses? Especially, is there any syntactic order of difficulty among the four types of relative clauses: OO, OS, SS, and SO types? 2. Previous studies on ranking difficulty of relative clauses show the relevance of the Parallel Function Hypothesis, the Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis (i.e. center embedding difficulties), and the Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis (preference for relativized subjects over relativized objects). Will the result of this study show the same as what these hypotheses claim? 3. What is the role of transfer in acquiring English relative clauses for Korean students? 4. What is the relationship between a student’s TOEFL score and her/his acquisition of relative clauses? 4.2. Hypotheses 1. Regarding the order of syntactic difficulty, I hypothesize that the PDH, and the NPAH would be supported in this study. I also hypothesize that center embedding and relative pronoun fronting would be major factors that increase the complexity. Therefore, I hypothesize that SO sentences such as John, whom we love, left the town, would be the most difficult and error producing type because it includes both center xxviii embedding and relative pronoun fronting. OS would be the easiest and SS, OO, and SO, from the easiest to the hardest. 2. I hypothesize that PDH and NPAH will be validated and that PFH will not. 3. I assume that relative pronoun fronting is more difficult than center embedding for Korean students who are stronger in Korean than English, because they have tendency to interpret the English sentences in Korean. SS and SO relative clauses have center embedding in English but not when translated in Korean. This is explained as language transfer from Korean. 4. I also hypothesize that the TOEFL score shows a strong correlation with acquisition of relative clauses. Chiang’s study also shows that second language learners produce relative clauses more when their overall proficiency is higher. 4.3. Methodology 4.3.1. Subjects Initially, 4 Korean speakers and 5 speakers of English participated in a pilot study. The subjects for the main study were 10 Korean students studying at Arizona State University. Subjects included 6 females and 4 males. The average age was 27.6 years old. 8 of them were graduate students and 2 were undergraduate students. Their average period of stay in USA or English speaking counties was 1.5 years. Their average time studying English was 11 years. Most of them learned English in a formal classroom environment in Korea. The average self-reported TOEFL score was 594 , and all of the subjects scored above 560, which shows that all of them are at an advanced level of English. xxix 4.3.2. Materials The materials used in this study are a one-page questionnaire (see appendix 1). The questionnaire contains 12 sets of questions requesting the subject to combine two sentences into one. The first 2 or 3 words were written on the paper in order to direct the answer toward the structure this paper is expecting to examine. Those 12 questions are composed of 3 sets of 4 different types of relative clauses, that is OO, OS, SS, and SO types. From the pilot study, I found that without guiding words, subjects tend to switch the main sentence and the relative clauses, which may hinder observing the expected usage. Therefore, by providing the first couple of words, I confined the possible expression and thus pushed the subjects to produce desired relative clause types. From the pilot study, I found that both native and non-native speakers of English prefer to use subjective relative clauses, and one way of doing it is through changing the voice to passive voice. Therefore, I included the passive voice to see whether they maintain that the voice or change it to active voice. TOEFL scores are asked about in the survey question (Appendix 2), in order to measure the correlation between RC performance and TOEFL scores, which I assumed to represent overall language proficiency. 4.3.3. Procedure In the first pilot study, I used a questionnaire with 3 different writing tasks (Appendix 4). The first task was answering the definitions of words, the second task was xxx to describe a picture, and the third task was combining sentences. The findings from the pilot study were that both native and non native speakers of English preferred subjective relative clauses, and that Korean students didn't use relative clauses in describing the picture, but all native English speakers used relative clauses in that task. However, the result was not enough to show the order of difficulty, which I intended to find in this study. Therefore, I revised the questionnaire by expanding the third part of combining task. With the revised questionnaire, I tested with native English speaker and got the same answer I expected. Therefore, I used them for the main research. Each subject was given a page of questionnaire (Appendix 1) and a survey of learning background information (Appendix 2). There were no time limit; however, to prevent consulting the dictionary or getting other help to fill out the questionnaire, I gathered the data on the spot. Before I gave the questionnaire to the subjects, I explained that the data would be stored without a connection to their names. It took 5 to 10 minutes for them to finish. xxxi CHAPTER 5. 5.1. RESULTS & DISCUSSION The Order of Difficulty The results show that in terms of amount of usage, SS and SO types were produced the most, as shown in table 3. Among the total 120 sentences, SS and SO types were produced 31 times respectively, OS were used 27 times, and OO types were used 26 times (see table 3). Table 3. Number of relative clauses and errors NUMBER OF USAGE GRAMMATICAL ERROR COMBINING ERROR AVOIDANCE SS SO OS OO 31 5 31 3 27 1 2 5 26 2 1 No RC (AND) TOTAL 5 5 120 11 2 11 In terms of number of usage of each type, the data describes that to Korean students when antecedents are functioning as subjects in the main sentences, they are easier to access. At first glance, this result seems to be different from what Kuno (1974) hypothesized in the PDH. According to Kuno, center embedding is the major obstacle in relative clause production. On the contrary, my results show that both types with center embedding process were used the most. It indicates that to Korean students center embedding is not an obstacle to production or access at all, which is the same as I hypothesized. Table 3 also indicates the avoidance pattern, that OO and OS types were avoided 5 times each, whereas SO types were avoided only once, and SS was not avoided xxxii at all. This goes along with above finding that to Koreans English center-embedding is not a big hindrance in terms of accessibility, on the contrary, non-center embedding in English were easily accessed. The reason can be found in transfer from Korean language which is overruling the English. Due to the exact opposite structure of Korean and English, center embedding in English means non-center embedding in Korean, and vice versa. Therefore, we can conclude that center embedding is one of the major difficulty factors shown here, but due to overruling transfer, the center embedding in L1 causes avoidance of the OO and OS types. Kuno’s PDH is supported by the result. I will discuss this in detail later in this chapter. The number of errors explains the syntactic difficulty differently of center embedding. In table 1, the grammatical error rate shows the inter-sentential grammatical errors committed by subjects. Five errors were made in the SS type, which comprises the 45% of total errors. Three errors were also made in SO types. These facts support Kuno (1974)’s hypothesis claiming the difficulty of center embedding process. Moreover, only one error was made in OS types, and two errors were made in OO types, which explains relative easiness when center embedding is not included. The results reject the Parallel Function Hypothesis. In order to validate what Sheldon (1977) claimed, both SS and OO should be the easiest one. Even though SS type is used the most, OO type is produced the least. In addition to that, there’s no difference in the total number of usage of SS type and SO type. Errors were made more when the function was the same. Errors in SS and OO types are 7, meanwhile, only 4 errors were made in SO and OS types. Neither the frequency of usage and error rates supports the PFH. xxxiii In this paper, as for Accessibility Hypothesis, we are only looking for the upper part of the hierarchy, which is subject NP and Object NP. The pilot study clearly shows a preference for subjective relativization. The full study also supports that we cannot deny NPAH, because as far as the function in the main clause is same, subject relativization is used more often. Total number of subject NP usage is 58, whereas, total number of object NP usage is 57. Even though the difference in the number is only one, the subject NP is more accessible, which supports Keenan and Comrie’s NPAH. In terms of errors, 6 errors were made in subject NP, and 5 errors were made in object NP. Among 6 errors in subject NP, 5 of them were made in SS types, which indicates the big possibility that the errors were caused by center embedding, rather than being in subject NP. Therefore, this error analysis also supports the NPAH. 5.2. Data Analysis In this section, errors and avoidance strategies are analyzed. These errors were examined across different types of RCs. Table 4 shows the relative clause production by the 10 Korean subjects and their TOEFL scores. The correlation between the performance on RCs and the TOEFL score was examined. In measuring RC performance, errors and avoidance strategies were excluded from correct usage, and RC performance was calculated in a percentile. The correlation coefficient shows 0.35, which is very low (Table 5); however, only seven TOEFL scores are known, therefore, we need more data to confirm the result. Table 4. Number of RC Production of 10 Korean Subjects. xxxiv SS SO OS OO Errors Avoidance Errors & Avoidance Errors & Avoidance (%) RC Performance (%) TOEFL Score S1 3 3 2 2 3 2 5 42 58 N/A S2 3 3 3 3 0 0 0 0 100 623 S3 3 3 3 3 0 0 0 0 100 580 S4 3 3 2 4 0 1 1 8 92 600 S5 3 3 3 3 1 0 1 8 92 N/A S6 4 3 2 3 3 2 4 33 67 612 S7 3 3 5 1 2 2 4 33 67 N/A S8 3 3 3 3 0 0 0 0 100 597 S9 3 4 2 3 0 1 1 8 92 583 S10 3 3 2 1 2 3 5 42 58 563 N/A : not available Table 5. RC Performance (%) TOEFL Score 5.2.1. RC Performance (%) TOEFL Score 1 0.35 1 Error Analysis Table 6. Error Types Produced By 10 Korean Subjects Error Type No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 Total Description Pronoun retention Relative clause marker selection Adjacency Be verb omission Misplacing subject in objective RCs Modifying wrong antecedent Number of occurrence 2 1 2 4 2 2 13 Table 6 shows error types found in this research. Gass (1980) introduces four error types in the production of RCs; 1) relative clause marker omission, 2) pronoun retention, 3) relative clause marker selection, and 4) adjacency. In this study I found the same error types Gass mentioned except relative clause omission. In addition to that, I Total 31 31 27 26 11 11 21 18 83 N/A xxxv found ‘be verb omission’, ‘misplacing a subject in objective RCs’, and ‘modifying wrong antecedent’ error types. Following are example of errors from the subjects : 5.2.1.1. Error type 1. Pronoun retention Two errors were made: The dress you bought it at Sears fits well on you. The boy …whom you met him at school. This error is definitely not from transfer because in Korean there is no pronoun retention except genitive relative clauses. The above sentences are both SO type RCs. Therefore, I could find the reason in processing, which is a language-independent factor. Objective relativization requires relative pronoun fronting. However, it could be interpreted as that the subject 6 and the subject 10 may have not paid enough attention to the form for these specific sentences, or didn’t acquire relative pronoun fronting fully yet. It would require more research to link pronoun retention to SO difficulty. 5.2.1.2. Error type 2. Relative clause marker selection One error was made: My mother made apple pies what I love so much. The subject is using what instead of that as an objective relative pronoun. What is also used as a relative pronoun in certain sentences. Those clauses are called free relative clauses and have no head noun in the main clause. They are the result of either the head noun deletion rule or the free relative substitution rule that allows what to replace a head xxxvi noun and relative pronoun in subject, object or predicate position. For example, My mother made what I love so much is a correct sentence of using free relative clause. What is an interrogative pronoun and shows the similar syntax with relative pronoun. For example, what is an interrogative in My mother asked what I love. Only the semantics is different. Errors in relative marker selection can also be understood as part of transfer. Korean has an invariable marker and therefore, it is predictable that Korean students will have trouble in choosing the appropriate relative pronoun among variable relative markers. 5.2.1.3. Error type 3. Adjacency Two errors in adjacency were made by the Korean subjects: The boy is my brother whom you met at school. The research required 1000 subjects which was directed by ETS. Error type 3 shows that the subject tried to avoid center embedding. In both sentences, the function of the antecedent in the main sentences is a subject, and therefore, to be modified by a relative clause, center embedding is inevitable. As Kuno claimed, center embedding is one of the obstacles to learners and this error supports Kuno’s hypothesis. 5.2.1.4. Error type 4. Be verb omission Four errors were made: The research which (was) directed by ETS …. The research which (was) directed by ETS …. xxxvii The lady who (is) carrying a huge globe is my teacher. Megan who (is) 16 years old won the … Error type 4 is the most frequent error type. This is very interesting because it is not mentioned in previous studies. I think the error came from the over-generalization of the relative pronoun + be deletion rule. The subject, who knows this rule vaguely, misapplied the rule and deleted only the be verb. The error occurs with both auxiliary and copula verb. The relative pronoun +be deletion rule applies when a restrictive relative clause containing 1) a relativized subject and a verb in the progressive aspect, 2) a relativized subeject and a verb in the passive voice, and 3) a relativized subjects followed by be copula and a complex adjective phrase. 5.2.1.5. Error type 5. Misplacing or omitting subject in objective RCs Two errors were made: The dress which bought you at Sears… We read the book that (John) recommended. The first error in type 5 occurred due to over-generalization. The subject knows that the objective relative pronoun should be fronted. Therefore, which was moved to the front. However, after changing the order of the object, she changed the order of subject you also. The second error in type 5 can be interpreted as either mismatching the antecedent, or overgeneralization of the deletion rule. In the latter case, the subject might xxxviii have thought the sentence to be We read the book that (was) recommended (by John). This is the same phenomenon as be-verb omission, which was mentioned in error type 4. 5.2.1.6. Error type 6. Modifying wrong antecedent Two errors were made: Jane Austin who were loved by many readers wrote several novels. Jane Austin loved by many readers wrote several novels. The original two sentences in question 12 are Jane Austin wrote several novels. They were loved by many readers. The above two are errors of modifying the wrong antecedent. It is an error because the pronoun in the second original sentence, they, cannot indicate Jane Austin. This error shows the subject preference (SO +SS). This sentence is originally intended to be OS type. However, two subjects changed it to the SS type, which involves center embedding. This is another bit of evidence for the above finding that to Korean students center embedding may not be much of a big hindrance. I also think that the reason they were confused in finding the right antecedent is due to transfer. The pronoun they is usually thought of as a person. In Korean, we use two different words to indicate they: kudul for persons, and kuguttul for things. Therefore, the subject at first glance might have thought that they would indicate a person, which is Jane Austin in the sentence. 5.2.2. Avoidance Strategy Analysis xxxix In English, there are several ways to replace relative clauses. (15) can be replaced by an attributive adjective phrase as in (16). (15) The man who has only one eye stared at me. (16) The one-eyed man stared at me. However, RCs cannot be replaced by attributive adjective phrase all the time. (18) sounds incorrect if replaces (17). (17) The man who ate the whole pie is walking a dog. (18) *The [whole pie ate] man is walking a dog. Another way to replace RCs is to use two independent sentences, as in (19), or two clauses conjoined with a conjunction, as in (20). However, as Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999, p571) indicate, it is “more wordy and less elegant”. (19) The man ate the whole pie. He is walking a dog. (20) The man ate the whole pie, and he is walking a dog. (20) is not embedding, and all three ways to replace RCs are less complex than RC structures. Therefore, all these can be used as avoidance strategies. Among them, the first one was found in a pilot study by an English native speaker, who avoided (21) and produced (22). (21) The man who is wearing a blue cap is walking a dog. (22) The blue capped man is walking a dog. In this study, conjoining with the conjunction and is used as an avoidance strategy. It is a basic and easy way to combine sentences. There is no complex process in coordination. Subject 1 and subject 10 used such a conjunction strategy. Subject 1 used xl conjunction in questions 6 and 12, and subject 10 in questions 2, 6, and 12. Questions 2 and 6 are OO types and question 12 is OS type. Their responses follow. Q2. We read the book and John recommended it. Q6. The police questioned the man and we suspected him. The police questioned the man and we suspected him. Q12. Jane Austin wrote several novels and they were loved by many readers. Jane Austin wrote several novels and they were loved by many readers. Question 2 and 6 require the process of relative pronoun fronting, and question 12 has a passive voice embedded sentence. Subject 1 also made an error in Q2, which shows that OO types may be more complex. The other avoidance strategy is more subtle. In it, subjects still produce relative clauses but change the type. The underlying reason can be either avoiding difficult RC types to adopt easy ones, or just choosing what seems more natural to them. The patterns of this type of avoiding strategy are shown in a way to avoid relative pronoun fronting. Two of the errors were from OO to OS, and one is from SO to SS. All of them were changed from object NP to subject NP. Q2. We read the book. John recommended the book. We read the book that John recommended. (OO type. Expected answer) We read the book which is recommended by John. (OS type. Shows avoidance of pronoun fronting and supports NPAH) Q6. The police questioned the man. We suspected him. The police questioned the man we suspected. (OO type. Expected answer) xli The police questioned the man who was suspected by us. (OS type. Shows avoidance of pronoun fronting and supports NPAH) Q10. The actor is famous. We expect to see him tonight. The actor whom we expect to see tonight is famous.(SO type. Expected answer) The actor who is famous is expected to be seen tonight. (SS type. Shows avoidance of pronoun fronting and supports NPAH) The subjects changed the active voice to the passive voice to make a relativized object a relativized subject in all 3 examples of Q2, 6, and 10. The same phenomenon was discovered in the pilot study of the native English speaker’s production of relative clauses. They preferred relativized subjects rather than relativized objects. This supports Keenan and Comrie’s Accessibility Hierarchy Hypothesis. However, the opposite case was also found. Subject 4 changed the passive voice to active voice and preferred a relativized object; this happened only once. 5.3. Discussion This study analyzed Korean learners’ production of English relative clauses through the task of combining two sentences. In analyzing the results, in addition to the number of RCs they produced, errors and avoidance strategies used by subjects were considered, especially in analyzing the syntactic difficulty. The results show that to Korean students, SO and SS types were most accessible, even though they were more complex and error causing types. I found the xlii reason in transfer. As I mentioned earlier and as Kuno (1974) claims Korean is an SOV language, whereas, English is an SVO language. In SOV languages, relative clauses are pre-nominal modifiers, meanwhile, in SVO languages, relative clauses are post nominal modifiers. I found that many Korean learners of English have a tendency to translate English sentences into their mother tongue, Korean, when they produce them. It is especially strong when the syntax is more complex, because those sentences require conscious thinking to produce them. Translation is one kind of common learning strategy students use. A study by O’Malley et al (1985), on identifying the range, type and frequency of learning strategies used by beginning and intermediate ESL students, categorized learning strategies into meta-cognitive strategies and cognitive learning strategies. Translation is considered to be a cognitive strategy. They discovered that intermediate-level students tend to use proportionately more meta-cognitive strategies than students with beginning level proficiency. In the present study, we found the transfer, in relation with L2 proficiency. In producing L2 sentences, when the L1 is stronger than L2, transfer is shown more; when the L2 is improved and is as strong as the L1, the L2 is not affected by the L1 anymore. When we apply Kuno (1974)’s Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis to the Korean students’ production of relative clauses, we can find that Korean structure influenced the results in a positive way; this reduced the perceptual difficulty of English relative clauses’ center embedding procedure. Table 7 shows the process involved in producing relative clauses comparing English and Korean. As for center embedding, Korean and English are totally opposite. Examples of each type of sentence are given in 1 to 4. Relative clauses xliii are in brackets, showing the contrast of English and Korean clearly in terms of center embedding. Table 7. Processes involved in producing RCs in comparison with English and Korean Relative pronoun substitution Relative pronoun fronting Center embedding Yes No Yes No No No SS English Korean SO English Korean Yes No Yes No Yes No OS English Korean Yes No No No No Yes OO English Korean Yes No Yes No No Yes 1.OS Type I love the man [who has a red sports car]. Na-nun [Pbalgan sports car-lul I-NOM red kajigo itnu-N] sports car-ACC have namja-lul -REL man-ACC saranghanda. love 2. SS Type The man [who has a red sports car] sent a letter to me. [Pbalgan sports car-lul Red kajigo itnu-N] sports car-ACC have 3. SO Type namja-ga naege pyunji-lul bonaetta. -REL man-Nom to me a letter-ACC sent xliv The man [whom I love] has a red sports car. [Nae-ga saranghanu-N] namja-nun Pbalgan sports car-lul kajigo itta. I-NOM love - REL red sports car -ACC have man-NOM 4. OO Type I love the red sports car [that he owns]. Na-nun [ku-ga soyooha-N] I-NOM Pbalgan sports car-lul saranghanda. he-NOM own-REL red sports car -ACC love As you see in the above examples, English and Korean is exactly opposite in center-embedding. Therefore, when the subjects think about the structure before they produce, they think in Korean, and therefore, the center-embedding in Korean language interferes; this explains why SS and SO clauses are used more often than OS and OO clauses. However, when they actually produce, center-embedding in English interferes; this explains why there are more errors made in SS and SO clauses than OS and OO clauses. xlv CHAPTER 6. CONCLUSIONS AND TEACHING SUGGESTIONS In this chapter, along with a conclusion, I introduce “4 steps” of teaching English relative clauses, the order of teaching RCs, and some other implicit teaching ideas on RCs. 6.1. Conclusion In sum, in this study, I found the following: 1. There is a syntactic difficulty order and also an accessibility order in different types of relative clauses. The order of accessibility shows SS/SO > OS > OO (left of > shows the more used one). The order of syntactic difficulty is OS > OO> SO > SS (left of > shows the easier one), which is the order of difficulty explained in terms of the process involved in RC production. 2. The results support Perceptual Difficulty Hypothesis and Noun Phrase Accessibility Hierarchy. On the other hand, Parallel Function Hypothesis was rejected. 3. The role of the transfer was found to be significant in this study. However, the pattern of transfer found in this study is different from the previous studies. Transfer influenced the perceptual difficulty of RC, and is shown in access and avoidance strategies rather than in errors. English relative clauses with center embedding is translated into Korean with no center embedding, and therefore, becomes easier for Korean students to access, and vice versa. 4. The relationship between TOEFL score and RC performance was not clearly shown in this study, but more study is needed. xlvi 6.2. Teaching Suggestions: 4 Steps. From the results of the present study, I propose the teaching orders and teaching ideas. The results show that many of the errors were made by overgeneralization of the grammar rules, that is, students’ lack of clear knowledge of the RC structure. Therefore, it is very important to teach students the rules how to make relative clauses explicitly. Since many errors were made due to overgeneralizing the relative pronoun deletion rules, it is also necessary to teach them the relative pronoun deletion rules clearly. As for teaching orders, I suggest to follow the order found in the present paper, that is, teach OS type first, and then, OO, SS, SO types. This is the order of difficulty according to the process involved in RC production. If we follow this order, we will teach the common process of identifying the identical NP and relative pronoun substitution first, and then add relative pronoun fronting, and finally, will teach the type with center embedding in addition to the previous processes. As for explicit teaching, it is important to teach students the process of RC formation step by step. Following is an example of the 4 steps I suggest in teaching the formation of relative clauses. First, start with two sentences like (23a) and (23b). (23) a. I know a girl. b. The girl likes the summer in Arizona. Step 1. Find the noun that occurs in both sentences. I know a girl. xlvii The girl likes the summer in Arizona. Step 2. Decide the main sentence and the subordinating sentence. I know a girl. – main sentence The girl likes the summer in Arizona. –subordinating sentence Step 3. Insert the subordinating sentence in a bracket, after the noun that will be modified. I know a girl [the girl likes the summer in Arizona]. Step 4. Replace the noun in the embedded clause with a proper relative pronoun and move it to the initial position of the embedded clause. I know a girl who likes the summer in Arizona. First, ask students to find the identical NP from both sentences, one of which will be an antecedent and the other will be replaced by a relative pronoun. Second, ask students to determine the main sentence and the subordinating sentence. Third step is to bracket the subordinating sentence and insert it after the modified NP. Celce-Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) suggest that this bracketed embedded sentence will focus students’ attention to identical NP and easier to replace with relative pronoun. The final step is to replace the noun in the embedded clause with a proper relative pronoun and move it to the initial position of the embedded clause. There is no movement in the above sentence because the relative pronoun is a subject and it is already in the initial position. Meanwhile, in the case of object relative pronouns, movement of the relative pronoun is supposed to occur in order for it to be adjacent to the modified antecedent. The benefit I expect from explicit teaching of the 4 steps that I introduced above is that it gives the students the clear grammar rules of RCs, which some people cannot xlviii easily acquire without conscious attention to the structure. These grammar rules will help students to self correct when they make mistakes. In the ESL environment, these criteria can also be learned inductively from other people’s speech. However, in EFL environment, because of the lack of enough input, students can rarely get these rules exclusively through implicit teaching. However, we still have to consider other variables such as the purpose of the lesson and the age of the students. If the goal of the lesson is to teach them the grammar so that they can produce the correct usage, explicit teaching can help students in many ways. On the other hand, if the lesson is designed to encourage communication, and students are expected to be intimidated by the grammar rules, or the age of the students are under the age of their early teens, students might not benefit from explicit teaching. Therefore, I introduce some implicit teaching ideas in the following section. 6.3. Implicit activities From the pilot study, I found that Korean students used no relative clauses when they were not required even though they showed their clear knowledge of RCs in response to other questions. On the other hand, all the native English speaking students used relative clauses more than once in describing a picture, where RCs are not required. This means that Korean students, even though they know RC structures, hardly use them in production. Therefore, I also suggest using implicit activities along with explicit teaching. Through implicit activities, students will learn not only the form and the meaning but also the use of the relative clauses. Implicit activities are good guided practices. For example, xlix after introducing the form of the relative clauses, give students authentic reading material such as a newspaper or magazine, and ask them to find and underline the relative clauses and color the relative pronouns. Students are supposed to determine to which head noun the relative pronoun refers. This activity will help them to get used to the form of the relative clauses and pronouns. Guessing word games can be used to practice relative clauses. This can be done as a small group or as a whole class. One student will be given a list of the words and he or she is to explain them using relative clauses. For example, if the word is a banana, he or she can say it is a thing that you eat, or it is a thing that is yellow. The other students are supposed to guess what the word is. It helps students to use the language with the purpose of explaining words. These activities can be modified in various types. Guessing word games can be used as “Twenty Questions”. Students will find out the word through asking questions using relative pronouns. This activity can involve more students to practice relative clauses. In addition to that, students can also be asked to describe their fellow students using relative clauses, for example, Mary is the girl who has two sisters or Kim is the boy who wants to be a millionaire. l REFERENCES Azar, B.S. (1995). Basic English Grammar A. New Jersey, Prentice Hall Regents. Azar, B.S. (1995). Basic English Grammar B. New Jersey, Prentice Hall Regents. Biber, D., Conrad, S. and Reppen, R. (1994). Corpus-based approaches to issues in applied linguistics. Applied Linguistics 15 (2), 169-189. Celce-Murcia, M., and Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The Grammar Book. An ESL/EFL Teacher’s Course. Heinle and Heinle Publishers. Chiang, D. (1980). Predictors of relative clause production. In R.C. Scarcella and S.D. Krashen (eds.), Research in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Mass.Newbury House. Doughty, C. (1991). Second language instruction does make a difference. SSLA, 13, 431469. Gass, S. (1980). An investigation of syntactic transfer in adult second language learners. In R.C. Scarcella and S.D. Krashen (eds.)Research in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Mass. Newbury House.132-141. Gass, S.M., and L. Selinker (1994). Second Language Acquisition. Hillsdale, New Jersey. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers. Keenan, E., and B. Comrie (1972). Noun phrase accessibility and universal grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 8 (1), 63-99. Kuno, S. (1974). The position of relative clauses and conjunctions. Linguistic Inquiry V (1), 117-136. li Larsen-Freeman, D., and M. H. Long (1991). An Introduction to Second Language Acquisition Research. New York. Longman. Sadighi, F. (1994). The acquisition of English restrictive relative clauses by Chinese, Japanese, and Korean adult native speakers. IRAL, XXXII (2), 141-153. Schachter, J. (1974). An error in error analysis. Language Learning 24 (2), 205-214. Schumann, J. (1978). The acquisition of English relative clauses by second language learners. In R.C. Scarcella and S.D. Krashen (eds.), Research in Second Language Acquisition. Rowley, Mass. Newbury House. Sheldon, A. (1977). The acquisition of relative clauses in French and English: Implications for language learning universals. In Fred Eckman (ed.), Current Themes in Linguistics. New York, John Wiley. Song. J.J. (1991). Korean relative clause constructions: conspiracy and pragmatics. Australian Journal of Linguistics, 11, 195-220. Yoon, J., (1993). Different semantics for different syntax: relative clauses in Korean. Working Papers in Linguistics, 42 (Sep.), 199-226. lii Appendix 1. QUESTIONNAIRE I. Please combine two sentences into one that begins with given words. 1. I know the girl. She wants to be a millionaire. I know the girl _________________________________________________________________ 2. He brought the news. The news surprised us. He brought the news ____________________________________________________________ 3. Jane Austin wrote several novels. They were love by many readers. Jane Austin ___________________________________________________________________ 4. We read the book. John recommended the book. We read ______________________________________________________________________ 5. My mother made an apple pie. I love an apple pie so much. My mother made _______________________________________________________________ 6. The police inspected the man. We suspected him. The police ____________________________________________________________________ 7. The research required 1000 subjects. The research was directed by ETS. The research ___________________________________________________________________ 8. The lady is carrying a huge globe. She is my teacher. The lady ______________________________________________________________________ 9. Megan won the Olympic good medal in swimming. She is 16 years old. Megan ________________________________________________________________________ 10. The boy is my brother. You met him at school. The boy _______________________________________________________________________ 11. The actor was absent. We expected to see him tonight. The actor ______________________________________________________________________ 12. The dress fits well on you. You bought it at Sears. The dress ______________________________________________________________________ liii Appendix 2. Please answer the following questions. Following questions are designed to help analyzing the research and will be kept anonymous. Gender: M__ F__ Age: _______ Academic status: Graduate__ Undergraduate__ or _______ Nationality: ______________ 1. How long have you been in US? _______________years. If you lived in other English speaking countries, please write the name of the country and the period you stayed. Country __________________ , Period ____________________ 2. How long did you study English? _____________________________________________ 3. How did you learn English? ______________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________ 4. What is your TOEFL score? ___________________________ 5. What do you think is your level of English? Beginner 1__ 2__ 3__ 6. How was the questionnaire in the previous page? Very easy __ 7. Intermediate 1__ 2__ 3__ Advanced 1__ 2__ 3__ easy __ medium __ difficult __ very difficult __ What was difficult? ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________ liv Appendix 3. 1. I know the girl. She wants to be a millionaire. I know the girl who wants to be a millionaire. OS 2. We read the book. John recommended the book. We read the book (that, which) John recommended. OO 3. The dress fits well on you. You bought it at Sears. The dress (that, which) you bought at Sears fits well on you. SO 4. He told us the news. The news surprised us. He told us the news that (or which) surprised us. OS 5. You met the boy at school. He is my brother. The boy (whom) you met at school is my brother. SO 6. The police questioned the man. We suspected him. The police questioned the man (whom) we suspected. OO 7. The research required 1000 subjects. The research was directed by ETS. The research which required 1000 subjects was directed by ETS. SS 8. My mother made apple pies. I love apple pies so much. My mother made apple pies (that, which) I love so much. OO 9. Megan won the Olympic gold medal in swimming. She is 16 years old. Megan who won the Olympic gold medal in swimming is 16 years old. SS 10. The actor is famous. We expect to see him tonight. The actor (whom) we expect to see tonight is famous. SO 11. The lady is carrying a huge globe. She is my teacher. The lady who is carrying a huge globe is my teacher. SS 12. Jane Austin wrote several novels. They were loved by many readers. Jane Austin wrote several novels which were loved by many readers. OS lv Appendix 4. QUESTIONNAIRE Part I. 1. What is a teacher? 2. What is a musician? 3. What is a dentist? 4. What is a typewriter? 5. What is a knife? 6. What is a bicycle? Part II. 1. Please explain the picture. lvi Part III. 1. Please combine 2 sentences into one. 1) The man is walking a dog in the park. He is wearing a blue cap. 2) The computer has a huge screen with it. My uncle gave me the computer as a present. 3) I know the girl. She is reading a book on the bench. 4) I saw the lady. John praised her so much. lvii Appendix 5. Different types of relative clauses SS The girl who loves Arizona is a friend of mine. OS I met the man who runs a storage. S(D)O The girls whom I love are joyful. O(D)O I found out the secret that he kept for ten years. S(I)O The boy to whom I gave the bread called me yesterday. O(I)O I saw the lady whom you wrote the letter to. SO(PREP) The table which I put the vase on is from Korea. OO(PREP) You have the book which I never heard about. SGEN The man whose name is John called you at noon. OGEN I love the man whose father is a lawyer. SO(COMP) The only person whom I am taller than is John. OO(COMP) ?I am the only person whom you are smaller than. S = Subject / O = Object / IO = Indirect Object / DO = Direct Object / OPREP = Object of Preposition / GEN = Genitive, possessive / OCOMP = Object of Comparison lviii Appendix 6. Relative Clause Production By 10 Korean Subjects No Expected 1 OS OO 3 SO 4 OS 5 SO 6 OO 7 SS 8 OO 9 SS 10 SO 11 SS 12 OS S1 OS OO* SO OS SO AND SS* OO SS SO SS* AND S2 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO SS SO SS OS S3 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO SS SO SS OS S4 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO SS SO SS OO S5 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO* SS SO SS OS S6 OS OO SO* OS SO OO SS OO SS* SS SS SO* S7 OS OS SO* OS SO OS SS* OO SS SO SS OS S8 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO SS SO SS OS S9 OS OO SO OS SO OO SS OO SS SO SS SO S10 OS AND SO OS SO* AND SS* OO SS SO SS AND * indicates a grammatically incorrect sentence Shaded ones are grammatically correct but in different forms from intended responses due to subjects’ avoidance strategies. lix Appendix 7. Subject Background Information S1 S2 S3 S4 S5 S6 S7 S8 S9 S10 NUMBER OR AVERAGE M M F=6, M=4 28 27 27.6 G G G=8, U=2 Gender F F M F F F Age 19 27 29 32 20 32 Graduate/ U G G G U G undergraduate Stay in US/ 0.5 1.7 1 3 1.5 1.2 English speaking country(years) Term of 5 10 11 10 10 10 studying English TOEFL 623 580 600 612 F 26 G M 36 G 3 1.8 1 2 1.67 10 23 14 10 11.3 597 583 563 594