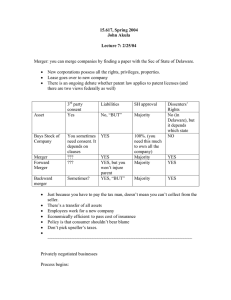

Merging Nonprofit Organizations The Art and Science of the Deal

advertisement