MEDIA CONSUMPTION AND EDUCATIONAL OUTCOMES: A Thesis by

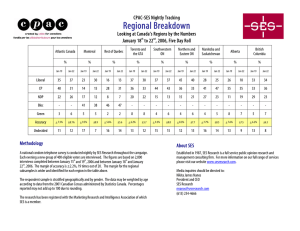

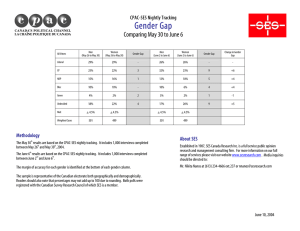

advertisement