Shellfish Aquaculture Development in Maryland and Virginia

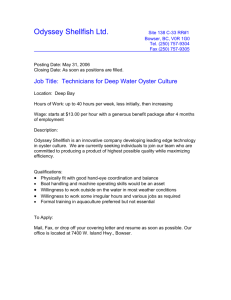

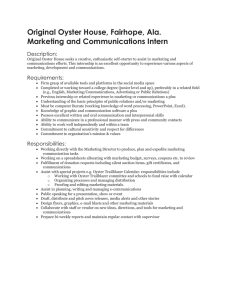

advertisement