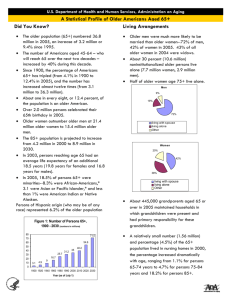

1 Executive Summary America’s older population is in the

advertisement