The Role of Investors in Acquiring Foreclosed Properties in Boston

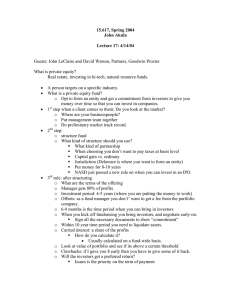

advertisement