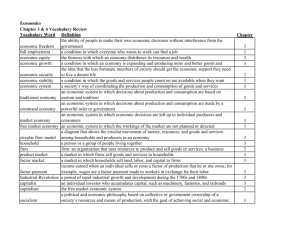

NATION’S HOUSING THE STATE OF THE 2 0 0 3 J

advertisement