PUBLIC SECTOR DUPLICATION OF SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION LOAN AND INVESTMENT PROGRAMS:

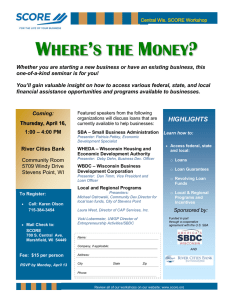

advertisement