KEY FINDINGS FROM THE EVALUATION OF THE SMALL BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION’S LOAN AND

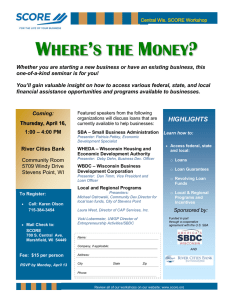

advertisement