I. Imaging of the Solitary Pulmonary Nodule II. Authors

advertisement

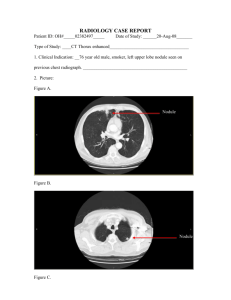

Back to Contents Page I. Imaging of the Solitary Pulmonary Nodule II. Authors Anil K. Attili, AFRCS, FRCR Lecturer in Thoracic Radiology Department of Radiology University of Michigan Ann Arbor Tel- 734-647-9780 e-mail- aattili@med.umich.edu Ella A. Kazerooni, MD, MS Professor and Director of Thoracic Radiology Department of Radiology University of Michigan Ann Arbor Tel- 734-936-4366 Fax-734-936-9723 e-mail- ellakaz@med.umich.edu 1 III. Issues: 1. The solitary pulmonary nodule: A. Who should undergo imaging? Special case: Estimating the probability of malignancy in a solitary pulmonary nodule Special case: Solitary pulmonary nodule in a patient with a known extrapulmonary malignancy IV. Key Points: - Further evaluation of a solitary pulmonary nodule incidentally detected on chest radiography is not needed when either of the following two criteria (MODERATE EVIDENCE) are met: 1) Nodule is stable in size for at least two years when compared to prior chest radiographs. 2) There is a benign pattern of calcification demonstrated on chest radiography. - Further evaluation of a pulmonary nodule showing either a benign pattern of calcification, fat and/or stability for 2 years or more on thin-section CT is not needed (MODERATE EVIDENCE) - In the absence of benign calcification, fat or documented radiographic stability for at least two years, the choice of subsequent imaging strategy to differentiate between benign and malignant nodules is critically dependent on the pretest probability of malignancy. 2 a) CT should be the initial test for most patients with radiographically indeterminate pulmonary nodules. (MODERATE EVIDENCE) b) 18 FDG -PET has a high sensitivity and specificity for malignancy. (STRONG EVIDENCE), and is most cost-effective when used selectively in patients where the CT findings and pretest probability of malignancy are discordant. - Multidetector CT scanners with improved spatial resolution, and the use of MDCT for lung cancer screening, have led to the increased detection of small (< 1 cm) pulmonary nodules. Nodules are categorized on CT as either i) solid ii) part-solid (mixed solid and ground glass attenuation) or iii) non-solid (pure ground glass attenuation). The imaging strategy for the further evaluation of small solid pulmonary nodules in the absence of a known primary malignancy is based on nodule diameter (MODERATE EVIDENCE) 1. For 4-10-mm in diameter solid nodules, a strategy of careful observation with serial thin-section CT scanning is recommended at 6, 12 and 24 months. In patients with a known primary neoplasm, initial re-evaluation at 3 months is recommended. 2. For solid nodules larger than 10-mm in diameter, further evaluation with either 18 FDG -PET, percutaneous needle biopsy or video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) is recommended. - Part-solid nodules (solid and ground glass components) and non-solid nodules (pure ground glass) detected at lung cancer screening have a higher likelihood of malignancy than solid nodules; therefore, tissue sampling (percutaneous CT-guided biopsy or VATS) 3 is recommended (MODERATE EVIDENCE). For nodules less than 1-cm where this may not be possible, close serial CT evaluation at 3 month intervals in recommended. 4 Issue 1: Who should undergo imaging? Summary: Pulmonary nodules are commonly discovered incidentally on chest radiographs or computed tomographic (CT) examinations. There are four imaging findings that are highly predictive of benignity. If one or more of these 4 features is identified, no further diagnostic evaluation is required. If there is doubt on CXR about the presence of these findings, CT should be performed for better anatomic resolution. 1) nodule calcification on CXR or CT that is either central, diffuse, popcorn or laminar (concentric rings) 2) fat within a nodule on CT is highly specific for hamartoma 3) a feeding artery and draining vein indicates an arteriovenous malformation 4) a pleural-based opacity with incurving bronchovascular bundles associated with adjacent pleural thickening or effusion is a characteristic of rounded atelectasis (comet tail sign) Stability on chest radiographs for two years or more has been considered an indicator of benignity. This is based on retrospective case series in which surgical resection was performed. A recent re-evaluation of the original data shows that the two year stability criterion on CXR has a predictive value of only 65% for benignity, limiting the use of this criterion. 10-20% of small or subtle lesions interpreted as possible solitary pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs do not actually represent solitary pulmonary nodules, but lesions in the ribs, pleura, chest wall or artifacts. When there is doubt about the presence of a nodule on CXR, further imaging is required. 5 Issue 2: What imaging is appropriate? Summary: Management strategies for a SPN are highly dependent on the pretest probability of malignancy. The strategies include observation, resection and biopsy. CT should be the initial test in most patients with a new radiographically-detected indeterminate SPN. Advances in technology have improved the ability to differentiate between benign and malignant nodules using nodule perfusion and metabolic characteristics, as can be evaluated with intravenous contrast enhanced CT, 18FDG -PET and SPECT. 18 FDG -PET should be selectively used when the pretest probability and CT probability of malignancy are discordant. If the pretest probability of malignancy after CT is high, 18FDG -PET is not cost effective. Recommendations for the use of computed tomography, positron emission tomography, watchful waiting, transthoracic needle biopsy and surgery in the evaluation of an indeterminate solitary pulmonary nodule are shown in table 5. Special Case: Estimating the Probability of Malignancy in Solitary Pulmonary Nodules Summary The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of management strategies for evaluation of SPNs is highly dependent on the pretest probability of malignancy. Bayesian analysis and multivariate logistic regression models can be used to predict the likelihood of malignancy for a given nodule, and perform equal to or better than expert human readers of imaging tests. Using Bayesian analysis, 18FDG-PET as a single test is a better predictor of malignancy in SPNs than standard CT criteria. 6 Special Case: Solitary Pulmonary Nodule in a Patient with Known Extrapulmonary Malignancy A SPN in a patient with an existing extrapulmonary malignancy deserves special consideration, as they are often detected on staging, follow up chest radiographs or CT. The etiology of these nodules is important to determine appropriate therapy in differentiating a new lung cancer from a pulmonary metastasis or nodule of another etiology, such as infection. In a level 2 (MODERATE EVIDENCE) retrospective study, Quint et al demonstrated that the likelihood of primary lung malignancy in such nodules depends on the histological characteristics of the extrapulmonary neoplasm and the patient’s cigarette smoking history. The medical records of 149 patients with an extrapulmonary malignancy and a solitary pulmonary nodule at chest CT were reviewed. The histologic characteristics of the nodule were correlated with the extrapulmonary malignancy, patient age and cigarette smoking history. Patients with carcinomas of the head and neck, bladder, breast, cervix, bile ducts, esophagus, ovary, prostate, or stomach were more likely to have primary bronchogenic carcinoma than lung metastasis (ratio 8.3:1 for patients with head and neck cancers; 3.2:1 for all other malignancies combined). Patients with carcinomas of the salivary glands, adrenal gland, colon, parotid gland, kidney, thyroid gland, thymus, or uterus had fairly even odds of having bronchogenic carcinoma or pulmonary metastasis (ratio 1:1.2). Patients with melanoma, sarcoma or testicular carcinoma were more likely to have a solitary metastasis than bronchogenic carcinoma (ratio 2.5:1). The results of this study were similar to an earlier study performed by Cahan et al in the pre-CT era. The authors analyzed thoracotomy results obtained for 35 years in over 800 patients with a history of cancer, and obtained similar odds ratios for bronchogenic carcinoma versus solitary pulmonary metastases in different primary malignancies, based on conventional radiographic detection of the SPN. 7 Table 5 Recommendations for the Use of Computed Tomography, Positron Emission Tomography, Watchful Waiting, Transthoracic Needle biopsy and Surgery in the Evaluation of an Indeterminate Solitary Pulmonary Nodule. Adapted from [86] Intervention CT 18 FDG-PET Indications When pretest probability is < 90% • • • • Watchful Waiting • • • • Percuteanous Transthoracic Needle Aspiration/Biopsy • • • Surgery • When pretest probability is low (10-50%) and CT results are benign When pretest probability is high (77-89%) and CT results are benign When surgical risk is high, pretest probability is low to intermediate (65%) and CT results are possibly malignant When CT results suggest a benign cause and the probability of nondiagnostic biopsy is high, or the patient is uncomfortable with a strategy of watchful waiting In patients with very small, radiographically indeterminate nodules (<10mm in diameter) When the pretest probability is very low (<2%) or when pretest probability is low (<15%) and 18FDG-PET results are negative When pretest probability is low (<35%) and CT results are benign When needle biopsy is non-diagnostic in patients who have benign findings on CT or negative findings on 18FDG-PET When18FDG -PET results are positive and surgical risk or aversion to the risk of surgery is high When pretest probability is low (20-45%) and 18FDG-PET results are negative When pretest probability is intermediate (30-70%) and CT results are benign When pretest probability is high and CT results are indeterminate (possibly malignant) • When 18FDG -PET results are positive • As the initial intervention when pretest probability is very high (> 90%) Figure 6. Suggested algorithm for clinical management of patients with solitary pulmonary nodules and average risk of surgical complications Back to to Contents Contents Page Page Back 8