The Emerging Role of the Chief Information Officer

advertisement

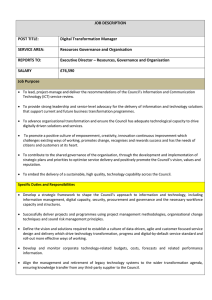

The Emerging Role of the Chief Information Officer Superstar or Supporting Act? Cranfield School of Management - April 2007 Professor Chris Edwards Rob Lambert So what are the options for the successful CIO: to become the organisation’s Chief Transformation office, a ‘superstar’ role with a Board position and a member of the inner sanctum; or to become a ‘supporting act’ in managing a collection of outsourcers working for the organisation’s new Chief Transformation Officer? Indications are that the rate of organisational change / transformation is increasing. In the public sector the emphasis placed on integration and efficiency has significantly risen (fuelled by Gershon and Lyons) and further reenforced by the ODPM’s 10-year vision, 'The Future of Local Government’. Improved service delivery, better dialogue with citizens and communities, strong political and managerial leadership and joined-up services are just some of the challenges currently facing the public sector. Each of these demands that such organisations must have the ability to transform. The private sector is not excluded from this revolution; one multi-national organisation reports 1,500 active change initiatives at one particular point in time. No doubt some of these are minor and involve few individuals, however many are significant in scale and complexity. It is no wonder many organisations report change overload! Information Technology (IT) is one of the primary components of such transformations in many organisations; unfortunately the literature abounds with statistics of IT failure. Often such failure is not of a technical nature but an organisational ‘failure’ to advantageously harness the new facilities provided by the software. It is becoming clear that IT as a vehicle of transformation is discredited in some organisations. Often learning between initiatives is limited. In some organisations each transformation initiative seems to be undertaken to standards set by the leader of that particular initiative. To pursue a nautical analogy each voyage (initiative) is undertaken rather like Columbus’s first expedition to the Americas, which must have been a planning and operational nightmare. Organisations require change to be managed more like a P&O cruise docking at Southampton: the required replenishments are radioed ahead; the waste is waiting to be taken off; all the consumables are ready to be loaded. Ten hours later the vessel is on its way to the next port, fully prepared to delight its new customers. The precise planning has evolved over many years and clearly has a direct effect upon P&O‘s bottom line; each day that passengers are cruising generates income. Maybe this analogy is exaggerated, but in some organisations each transformation initiative is like an adventure; they do not seem to be learning from each experience to ensure the next is more effective and efficient. The US has seen the growth of an infrastructure to support such change, referred to by Kaplan and Norton amongst others, as the creation of the Strategy Office supported by Strategy Maps. These, and all the other elements of creating tomorrow’s organisation, increasingly fall under the control of a single individual sometimes called the Chief Transformation Officer (CTrO). The domain of ‘change and transformation management’ has been thoroughly researched by academics over the years. Numerous ‘methodologies’ have been proposed to achieve successful transformation. In essence, common themes recur and these are shown in Figure 1. The first four elements are centered around developing an agreed change portfolio. The literature reinforces the criticality of the leadership team communally committing to a prioritised portfolio. The remaining six elements are involved with the detailed planning, delivery and review of the change initiatives. Recent research undertaken at Cranfield suggests that these six elements are necessary but they are insufficient, in themselves, to deliver the critical benefits. Realisation of these benefits is more closely associated with the formulation of an agreed change portfolio. The Emerging Role of the Chief Information Officer Superstar or Supporting Act? The research also indicates that organisations are more mature in programme execution but less so in portfolio formulation. Figure 1: Generic elements of successful transformation Portfolio formulation 1 Engender and reinforce an organisational culture of continuous change Exactly who in an organisation aligns, prioritises and coordinates the portfolio of business change initiatives? Who is responsible for creating organisational readiness for change? Who ensures that adequate business change resources are allocated to each initiative? Who mobilises the various groups that need to be involved in operationalising the change (IT, HR, etc)? Who tests and signs off the change as suitable in terms of efficiency and compliance? Some of these tasks are frequently allocated to a Programme Office but such a group often exists to provide administrative and support services only; not a truly managerial capability, with real responsibility and authority. The above questions relate to responsibility for the creation of the organisation’s tomorrow and, as such, it could be said to be the CEO’s responsibility. But then everything is the CEO’s responsibility and he/she only has 16 working hours in each day! In summary, it is less clear who coordinates and operationalises the creation of tomorrow’s business than it is to understand who delivers today’s business. The UK has seen a distinct rise in the number of advertisements for individuals with ‘Transformation’ and ‘Change’ in the job title, particularly in the public sector. Such a role is central to an organisation as it exclusively focuses upon generating tomorrow’s success. Logic suggests, and the job advertisements confirm, that there is a need for such an individual but what is their background; what are their core competencies? Would an effective Chief Information Officer be well positioned to fulfill such a transformation role? A brief consideration of the competencies required for the task of CTrO compared to those required for a successful CIO would suggest a significant similarity. For example, coordination of a variety of initiatives is central to both, as is the need to understand and act in a ‘political’ manner. Also the traditional IT ‘V’ 2 Understand the drivers and content of each change initiative at an early stage in the lifecycle 3 Align and filter initiatives to the strategic goals thus creating the change portfolio 4 Harmonise the strategic leaders team to support the change portfolio Programme execution 1 Develop the detailed business case and obtain approval / refusal for each initiative 2 Establish accountability and governance for each change initiative 3 Execute each change initiative and realise the intended business benefits 4 Manage the ongoing initiative portfolio, conflict, resources and inter-dependencies 5 Co-ordinate the elements of the change capability 6 Review, learn and improve the change capability diagram, beginning with a need to involve and understand the success criteria and terminating with a customer ‘sign off’, could be applied to broader change initiatives, albeit at a different level. Further, given the continuing drive towards IT outsourcing, many CIO’s are already focusing upon ‘demand management’. A recent presentation at Cranfield by Darin Brumby of First Group would suggest that some CIO’s are already undertaking this transformation role in content if not in title. If this is occurring it may well satisfy an aspiration cited by some CIO’s to be a permanent member of the Board rather than the more usual arrangement of being summoned as required. However some might ask why an organisation would want to promote an individual to a wider, but similar, role when the ‘IT products’ they presently deliver are the subject of such criticism and often reported failure. Perhaps one reason for this current failure is that the existing role is restricted to the information aspects of change; maybe this wider remit will increase the success rate for securing benefits from IT change. So what are the options for the successful CIO: to become the organisation’s CTrO, a ‘superstar’ role with a Board position and a member of the inner sanctum; or to become a ‘supporting act’ in managing a collection of outsourcers working for the organisation’s new Chief Transformation Officer? Clearly some of today’s CIO’s would choose the former and some may be required to become the latter. These speculations are embryonic, but early indications suggest such scenarios are becoming reality in some organisations. Our purpose in writing this article is to stimulate the debate so that current and aspiring CIO’s can plan their long term development. The issues discussed here are to be explored in more detail at a forthcoming conference at Cranfield. Professor Chris Edwards c.edwards@cranfield.ac.uk Rob Lambert r.lambert@cranfield.ac.uk © Cranfield School of Management