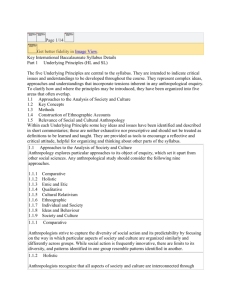

Wichita State University Libraries SOAR: Shocker Open Access Repository

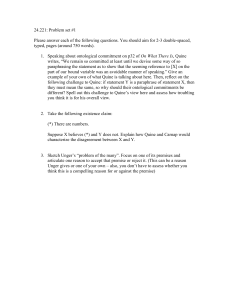

advertisement