From LHN & JN, On Quine

advertisement

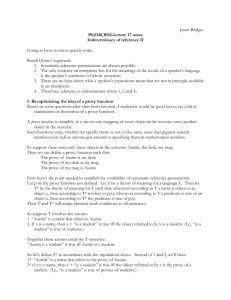

From LHN & JN, On Quine Language and “everyday observations” It may seem that while clearly theoretical sentences have empirical meaning only within the broader context of their containing theories, as holism asserts, this is not so for more mundane sentences, such as ‘The mail carrier will come again tomorrow’ or ‘There is an apple on the counter’. But there is also a substantial body of theory lying behind even these claims. As we explore in some detail in Chapter 5, Quine maintains that common-sense sentences about bodies (about mail carriers and apples) presuppose physical object theory, a theory which maintains that there are middle-sized objects (such that we say “here’s an apple,” rather than “it’s apple-ing”), of which apples are examples (but “red” and “on” are not). To learn physical object theory is to learn that apples and lots of other things are discrete objects (unlike snow which is scattered about in blankets or drifts), and we learn this theory as we learn language and master the principles of individuation (as we learn ‘a’, ‘the’, ‘an’, and so forth). Such principles, together with the notion (also part of physical object theory) that middle-sized objects are relatively enduring, makes it possible to wonder, to paraphrase Quine, if the apple on the counter is the one noticed yesterday. We have only begun to scratch the surface in terms of what this relatively simple sentence presupposes (consider, for example, the “is” of predication, and the predicate ‘is on the counter’). But perhaps it is sufficient to understand what Quine is urging. Even if we learn this particular sentence by mimicry (by adults pointing repeatedly to the relevant scene and repeating the sentence until we come to repeat it in appropriately similar situations), we don’t learn every sentence this way. The child who masters this sentence will eventually be able to come up with ‘My doll is on the table’, and ‘My doll is not on the table’, never having heard either sentence. At this point, we say that she or he “has caught on” to at least some of our most basic theory of the world concomitantly with catching on to our theory of language. This same body of theory, which tells us what to expect by way of the behavior of various kinds of objects, can yield the prediction “If no one has eaten it, this apple will still be on the counter in the morning.” “Seeing a body again,” Quine notes, “means to us that it or we or our glance has returned from a round trip in the course of which the body was out of sight” (1987a, 204; emphasis added). The notion of ‘seeing again’ requires a sophisticated notion of “the corporeality of things” (1087a, 204). In Quiddities, Quine explores the way in which the empirical content of common-sense sentences about ordinary bodies depends on physical object theory. William James pictured the baby’s senses as first assailed by a “blooming, buzzing confusion.” In the fullness of time a sorting out sets in. “Hello,” he has the infant wordlessly noting, “Thingumbob again!” Thingumbob: a rattle, perhaps, or a bottle, a ball, a towel, a mother? Or it may only have been sunshine, a cool breeze, a snatch of maternal baby talk: they are all on an equal footing on first acquaintance. Later we come to recognize corporeal things as the substantial foundation of nature. The very word ‘thing’ connotes bodies first and foremost, and it takes some effort to appreciate that the corporeal sense of ‘thing’ is peculiarly sophisticated (1987a, 204). “The corporeal sense of ‘thing’” presupposes what Quine in Word and Object calls “the immemorial doctrine of ordinary enduring middle-sized objects” (11). We consider the positions just outlined in more detail in Chapters 5 and 7. Here we note that the necessity, according to Quine, of language and the conceptual schemes it embodies for coherent and inter—subjective everyday experiences and observations.