Document 14737364

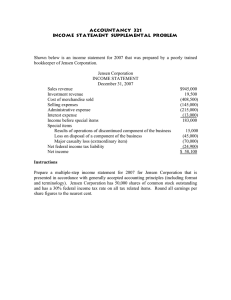

advertisement