Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence

advertisement

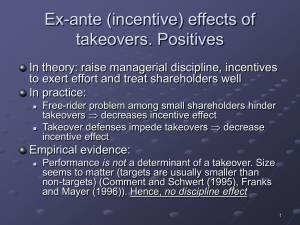

Nikolas R. Ortega Comments on Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence1 This Paper is a commentary on the findings of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence compared and contrasted with Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting. It seeks to examine the worth of current takeover laws with the mindset that fostering innovation should be the paramount goal of our federal and state governments when it comes to corporate law, specifically, the law that governs mergers and acquisitions. The Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence report offers a theory that corporate innovation is maximized in two scenarios. The first scenario is in a legal environment that creates a purely free market for corporate takeovers. The second scenario is where corporate law eliminates all takeovers. Shareholders, and in turn the United States economy, face concerns in both of these extreme scenarios. Because banning all corporate mergers is not realistic and it would infringe on fundamental shareholder rights, the government should err on the side of a free market for corporate takeovers. Therefore, United States legislatures should strive to create a corporate legal environment designed to balance the problem of suppressed innovation with the problems that would arise from corporate marauding in a purely free market for corporate takeovers. Maximizing innovation through the law, or at least creating a legal environment in which innovation can thrive, will enable United States companies to remain competitive in the global marketplace. Organizational Structure The organizational structure of this Paper follows: (1) The Paper begins with an “Introduction” section designed to provide a factual background on the authors of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence, and the thesis of this Paper. (2) Next, there is a section to provide the reader with a brief summary of the report this Paper analyzes. (3) After the summary of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence, there is a section that summarizes and compares a Journal of Finance article on the same topic titled Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting2 with 1 HARESH SAPRA ET AL., COMMENTS ON CORPORATE GOVERNANCE AND INNOVATION: THEORY AND EVIDENCE (2013) available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2210609. 2 Julian Atanassov, Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting, J. FIN., Jan. 30, 2013, available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jofi.12019/pdf. 1 Sapra and his coauthors report. (4) Then, there is a section that describes the current state of external mechanisms3 and their evolution. (5) Next is a section discussing the importance of innovation for corporations and, in turn, the economy. (6) Following the state of the law section is a section that analyzes the findings of Sapra and his coauthors while commenting on the current legal environment for innovation. This section also examines the importance of innovation and provides several examples of the positive impact of corporate innovation. (7) Finally, there is a conclusion section that summarily presents the essential points of this paper. Introduction On February 26, 2013, Haresh Sapra, Ajay Subramanian, and Krishamurthy V. Subramanian published a report regarding their findings on the relationship between corporate governance and innovation.4 The report is an international collaboration among business management scholars with Sapra representing the Booth School of Business at the University of Chicago, A. Subramanian representing the J. Mack Robinson College of Business at Georgia State University, and with K. V. Subramanian representing the Indian School of Business located in Hyderabad, India.5 The report details a theory its authors developed to show how both internal and external corporate governance mechanisms affect corporate innovation.6 Shortly before Sapra and his coauthors published Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence, Julian Atanassov published an article titled Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting that also explores the relationship between takeovers and corporate innovation. The Journal of Finance published Atanassov’s article on January 30, 2013, just one month before Sapra’s article was published. Atanassov is an assistant professor in the department of finance of the Lundquist College of Business at the University of Oregon. The Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence report is discussed first. Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence Report Sapra and his coauthors found that “there is a U-shaped relation between innovation and external takeover pressure, which arises from the interaction between expected takeover premia and private benefits of control.”7 The data supporting this conclusion came from observations before and after the occurrence of innovation.8 To 3 E.g. antitakeover laws. SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1. 5 Id. at abstract. 6 Id. 7 Id. 8 Id. 4 2 provide a more robust analysis, the authors took advantage of data about the differences in takeover pressure among the fifty states generated by anti-takeover laws.9 The Ushaped relationship the team observed signifies that “Innovation is fostered either by an unhindered market for corporate control, or by anti-takeover laws that are severe enough to effectively deter takeovers.”10 The graph below is a simple illustration of this relationship: This graph is a simple visualization of Sapra and his coauthor’s theorized relationship between the level of corporate innovation and the legal environment for corporate takeovers. The Y-axis represents the level for corporate innovation with corporate innovation increasing as the curve’s Y coordinate moves up the Y axis. The X axis is a spectral representation of the legal environment for takeovers. The further left the current state of the legal environment, the freer the market for takeovers becomes. At the leftmost point there is literally no regulation governing takeovers. The further right, the legal environment for takeovers becomes harsher. At the right most point, the law entirely prohibits corporate takeovers. As shown by the graph, innovation is maximized at the extremes of the legal environment axis. Conversely, innovation is minimized at the center of the two extremes. 9 Id. Id. 10 3 United States economic growth is directly affected by state and federal law as well as by institutions that influence corporate governance.11 In particular, it is clear that “economic growth results from firm-level innovation.”12 However, the exact manner in which laws and institutions influencing corporate governance affect firm-level innovation is less clear.13 Anti-takeover laws influence managers’ performance incentives, and managers’ incentives in turn influence their level of ingenuity.14 The point of the Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence report is to attempt to explain a possible way that “external mechanisms for corporate governance, such as anti-takeover laws, interact with a firm’s internal mechanisms, such as managerial incentive contracts, to affect firm-level innovation.”15 Represented graphically, the impact these external mechanisms have on firm-level innovation appears as a U-shape with the amount of firm-level innovation being the greatest in both legal environments where there is a purely free market for corporate control and legal environments that entirely eliminate the threat of corporate takeovers.16 If true, this theory is groundbreaking because previous theories have only posited monotonic17 relations, with either positive or negative slopes, between external mechanisms affecting corporate governance and firm-level innovation.18 In order to discover this previously unknown appreciated relationship between external mechanisms of corporate governance and innovation, a sufficiently variable data set is needed, as is true with all statistical relationships. The authors of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence found such a sufficiently varied data set by observing the differences between anti-takeover laws across the United States and the dates when legislatures passed the laws.19 Specifically, Sapra and his coauthors’ provided empirical support for their findings by: exploiting the staggered passage of anti-takeover laws by U.S. states as a source of cross-sectional and time-series variation in takeover pressure, and using ex-ante as well as ex-post proxies for innovation. [the authors conducted] several tests to account for the effects of unobserved determinants of innovation that may accompany the anti-takeover law passages. In particular, [the authors exploited] hand-collected data on patents filed by the specific subsidiaries/divisions of a firm that are located 11 Id. at 1. Id. 13 Id. 14 Id. 15 Id. 16 See Id. 17 Used in this context, “monotonic” means a straight line regardless of the value of its slope as opposed to a curve that possesses different slopes at different points of its horizontal axis. 18 Id. 19 Id. 12 4 outside the state of incorporation of the parent firm to isolate the pure effects of anti-takeover law passages on innovation.20 This analysis of external methods of corporate control as they relate to firm-level innovation yields the core thesis of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence. Put simply, the thesis is that “innovation is fostered either by practically nonexistent anti-takeover laws that permit an unhindered market for corporate control, or by anti-takeover laws that are severe enough to effectively deter takeovers.” To provide a concrete example of how their theory would affect a realistic situation, Sapra and his coauthors provide the reader of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence with a scenario about a pharmaceutical company.21 The sample scenario consists of a pharmaceutical company manager deciding between two mutually exclusive options.22 The first option is for the manager to invest in a project that would require a higher level of innovation, creating an entirely new drug.23 The second option is for the manager to pursue a generic substitute for a drug that is already on the market, requiring a smaller degree of innovation than creating an entirely new drug.24 Particularly, most uncertainties with a generic drug arise in the marketing context while considerably greater uncertainties arise in the research and development stage of creating a new drug.25 This hypothetical model has several constraints to simplify Sapra and his coauthors’ analysis. Primarily, the model follows the manager of the pharmaceutical company through two periods.26 After the first period, the model provides that there is a chance that an acquirer could take over the pharmaceutical company through a tender offer.27 After the second period, there is a qualitative assessment of the chosen project’s profitability. This model creates a scenario where the manager is forced to trade “off the positive effect of greater innovation on the expected unconditional payoff and the expected takeover premium against its negative effect on the expected lost of control benefits.”28 It is this tradeoff that is responsible for the predicted U-shaped relationship between innovation and external takeover pressure. Innovation and external takeover pressure have a U-shaped relationship because of the different incentives managers have at the extremes of a purely free market for takeovers and a market that does not allow for take overs. In the exact words of Sapra 20 Id. Id. at 2. 22 See Id. 23 See Id. 24 Id. (noting that “[l]aunching a generic substitute involves uncertainties due to customer demand and competition. In contrast, inventing a new drug entails additional uncertainties associated with the process of ‘exploration.’”). 25 Id. 26 Id. 27 Id. at 3. 28 Id. at 4. 21 5 and his coauthors the U-shaped relationship predicted by their analysis arises because: When the takeover pressure is very low, the low likelihood of a takeover implies that the expected takeover premium and the expected loss of control benefits are insignificant for both projects. Therefore, the manager chooses greater innovation because it has a higher expected unconditional payoffs. When takeover pressure is very high, the expected takeover premium and the expected loss in control benefits are both high. At high levels of takeover pressure, the takeover probabilities are similar for both projects so that the expected loss of control benefits are also similar. The expected takeover premium, however, is higher for the more innovative project because it depends not only on the probability of a takeover, but also on the size of the takeover premium conditional on a takeover. Consequently, it is again optimal to choose greater innovation when takeover pressure is high. For moderate levels of takeover pressure, the effect of the higher loss of control benefits associated with greater innovation dominates. It is therefore optimal for the manager to choose lower innovation to reduce the likelihood of losing her control benefits.29 In light of this relationship between external takeover pressures and innovations, this Paper posits that the optimal legal environment for corporate takeovers is one that falls on a position of the U-shaped relationship that is to the left of the innovation minimum but to the right of a purely free takeover market. Such a position would serve United States Economic interests only if it balanced the problems associated with a free takeover market against the problem of stifling corporate innovation. The extent to which the potential of a takeover, particularly a hostile takeover, stifles corporate innovation is the subject of the next article discussed. Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting Report Similarly but less broadly than Sapra and his coauthors, Atanassov seeks to explore an aspect of the relationship between innovation and takeovers. Specifically, Atanassov examines “how strong corporate governance proxied by the threat of hostile takeovers affects innovation and firm value.”30 Based on his extensive research, he concludes that firms are awarded less patents and receive less citations per patent if they are incorporated in a state that has passed an antitakeover statute than if the same firm was incorporated in a state with a legal environment that exposed the firm to the threat of takeover.31 The impact a change in the legal environment for takeovers has on corporate innovation typically takes two or more years to manifest.32 Interestingly, Atanassov finds “[t]he negative effect of antitakeover laws is mitigated by the presence of alternative 29 Id. at 4—5. Atanassov, supra note 2. 31 Id. 32 Id. 30 6 governance mechanisms such as large shareholders, pension fund ownership, leverage, and product market competition.”33 Atanassov begins by explaining that capital markets have the potential to stimulate economic growth through two channels.34 One way is through their ability to provide the necessary capital to fund projects that become profitable, but the other way, which is more important in this context, is “by providing the right incentives to managers through their monitoring and disciplining mechanisms.”35 Scholars generally agree on the manner in which capital markets impact economic growth when they do so by providing funding.36 They do not, however, agree on the way capital markets, specifically takeovers, impact economic growth through providing incentives to managers.37 In an attempt to combat the uncertainty covering the way that capital markets impact the economy through providing incentives to managers, Atanassov picks a prime example. He chooses the threat of takeover as the incentive provider, and he attempts to measure how this pressure impacts innovative decisions by top management.38 The purpose of his article is to “evaluate how the threat of hostile takeovers, which is considered one of the most extreme examples of external pressure on top management, impacts innovation.”39 Hostile takeovers are a double-edged sword when it comes to their direct effect on corporate governance and their indirect affect on the United States economy. “While hostile takeovers are considered one of the strongest corporate governance mechanisms to discipline managers and provide them with incentives to make value-enhancing decisions, numerous academics and policy makers argue that perhaps the greatest public concern about takeovers is that they stifle innovation.”40 In order to determine how the threat of hostile takeovers impact corporate-level innovation, Atanassov, like Sapra and his coauthors, utilizes the differences between the various state antitakeover laws.41 He argues that his methodology enables him “to evaluate the impact of hostile takeovers on the quantity and quality of innovative output measured by patents and patent citations. It also enables him to assess the importance of alternative governance mechanisms on disciplining managers when the threat of hostile takeovers is absent.”42 Next, Atanassov delves into some of the prevailing schools of thought seeking to 33 Id. Id. at 1. 35 Id. 36 Id. 37 Id. 38 Id. SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1. 39 Atanassov, supra note 2, at 1. 40 Id. 41 Id. 42 Id. 34 7 explain how hostile takeovers influence mergers. The first school of thought is the “agency view.”43 The agency view theory proposes that managers who are more effectively monitored perform better than managers who do not have anyone looking over their shoulder.44 As the theory goes, the threat of a hostile takeover counteracts the human nature to shirk when a person lacks either an effective monitor or an intrinsic motivation.45 The more managers fear losing their jobs in a hostile takeover, the more likely they are to pursue innovative courses of action.46 However, another school of thought predicts the opposite. Some scholars believe that when takeover pressure is too high, the current managers of a firm have little incentive to take risks in the form of innovative projects because they already believe their job is lost.47 These managers, according to this theory, “fear a hostile acquirer who will dismiss them after the innovation is created, and take advantage of the profits resulting from that innovation without bearing the costs for creating it.”48 One of the possible causes of this phenomenon is that shareholders lack the knowledge and experience of managers, and therefore, they cannot properly evaluate the risk-reward tradeoff of a manager’s innovative actions.49 Atanassov ultimately concludes that for firms incorporated in a state that passes an anti-takeover law, innovation is stifled.50 It is important to note that Atanassov’s theory predicts that corporate innovation declines as the threat of a hostile takeover weakens. See the graph below: 43 Id. Id. 45 Id. at 2. 46 Id. 47 Id. 48 Id. 49 Id. 50 Id. 44 8 The axes of the graph are exactly the same as in the Sapra graph on page three of this Paper. However, the curve has changed. According to Atanassov, corporate innovation is at its highest when managers are under the greatest threat of a hostile takeover, and as take over pressure wanes, so does their level of innovation. While this prediction is in line with Sapra and his coauthor’s prediction that when the legal environment is conducive to takeovers (i.e. a purely free market for takeovers), Atanassov’s model diverges when the legal environment prevents all mergers. Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence v. Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting It is interesting that despite analyzing almost the exact same issue at almost the exact same time while analyzing almost the exact same data sets,51 Sapra and his coauthors develop differing theories. The theories do not directly contradict each other, but when Atanassov’s model is extrapolated, the predictions are inconsistent. Atanassov’s model differs from Sapra and his coauthors’ when external mechanisms, whatever they may be, effectively eliminate corporate takeovers. In a legal or regulatory environment that forbids takeovers, Sapra and his coauthors believe that corporate innovation is 51 Both works base their findings on mergers and acquisitions data from roughly the last four centuries. Id. at 4; SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1, at 63—65. 9 maximized.52 However, in the same style of legal environment, Atanassov predicts that corporate innovation is minimized.53 There are several reasons this discrepancy may have arisen between the two models. The first reason that the models may differ is that Atanassov may have only intended to analyze the relationship between takeover pressure and corporate innovation in a legal environment with some form of takeover statute in play. Atanassov may have only attempted to analyze the relationship between innovation and takeovers in legal environments where mechanisms preventing takeovers are prevalent. In other words, he may have only contemplated legal environments starting at the minimum of the U-shaped graph54 and to the left. However, this is unlikely. If Atanassov analyzed a large enough pool of data that adequately represented the entire United States, he should have seem the same corporate innovation levels start to increase as jurisdictions became more hospitable to acquirers. This is assuming, of course, that Sapra and his coauthors are correct in their analysis. Another reason for the discrepancy could arise from the fact that qualitative attributes are notoriously difficult to measure. There are metrics for measuring some qualitative traits, but they are by no means perfect. There is great difficulty in charting characteristics such as the level of corporate innovation accurately. The articles discussed in this paper gravitate towards patents filed, but there are many innovations to which patents are not applicable. Finally and most likely, the two models may differ because Sapra and his coauthors sought to analyze the relationship between external takeover measures and corporate innovation across the entire spectrum of possible legal environments, real and hypothetical. It seems as though Atanassov was only interested in actual takeover legal environments. That is, Atanassov analyzed and reported on external takeover pressures only in measurable contexts while Sapra and his coauthors extrapolated their findings to both extremes of the legal environment spectrum. This is readily apparent by Sapra and his coauthor’s thesis: “Innovation is fostered either by an unhindered market for corporate control, or by anti-takeover laws that are severe enough to effectively deter takeovers.”55 There are no “unhindered markets for corporate control” in the United States the same way there are no jurisdictions with “anti-takeover laws that are severe enough to effectively deter takeovers” in the United States. Since there are no observable data sets (or certainly not enough to have a statistically significant sample) at the extremes of the legal environment spectrum, Sapra and his colleagues must have extrapolated their data. Atanassov did not take this approach. Instead, he analyzed real data and noticed a trend among United States 52 SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1, at 4—5. See Atanassov, supra note 2. 54 See supra p. 9 graph and accompanying text. 55 SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1, at abstract. 53 10 jurisdictions: Innovation is stifled for firms incorporated in a state that passes an antitakeover law relative to firms incorporated in states where the legal environment is more conducive to hostile takeovers.56 Observing this trend does not involve extrapolation because Atanassov does not attempt to predict what happens at the logical extremes of the legal environment spectrum. He attempts to create a workable model for how innovation levels respond to external takeover pressures in existing United States jurisdictions. This is not to say that Sapra and his coauthors are incorrect in their analysis of the relationship between takeover pressure and innovation. The differences between the two models are most likely created by Sapra and his colleagues extrapolation. A way to picture the problem is that Atanassov is focused only on a small portion of the Sapra et al. graph on page three, the portion halfway between the purely free market extreme and the minimum and extending to the minimum. This represents the observable portion of the spectrum of legal environments for takeovers in the United States. Sapra and his coauthors take a step back and attempt to take a broader view of the legal environment for takeovers. Using the data they observe they predict how innovation levels react to external takeover pressures across the entire universe of legal environments for takeovers. Sapra and his coauthor’s broader view of the legal environment spectrum for takeovers explains the seeming inconsistency between their theory and Atanassov’s. The two models are harmonized when Atanassov’s model is considered a subset of Sapra and his coauthors’ model. Atanassov’s theory would then accurately describe a subset of the data while Sapra and his coauthor’s theory describes the entirety of the data as well as an extrapolation into the areas where there are no data. The next section describes the current state and evolution of external mechanisms influencing corporate governance in the United States. This section is important because it provides the reader with information that will help him or her to appreciate how takeover attempts are governed and how this governance could impact innovation. While the articles discussed above shed light on the relationship between antitakeover laws and corporate innovation, they do not provide an in depth explanation of the current state or history of the external mechanisms that influence corporate governance in the United States. The Current State and Evolution of External Mechanisms Influencing Corporate Governance In response to a great increase in the number of corporate takeovers, state legislatures began enacting antitakeover statutes to protect domestic corporations from hostile takeovers. While the stated purpose of these laws is to protect investors by significantly weakening the ability of outside bidders to purchase a corporation, antitakeover statutes also safeguard local economies from economic and job losses by 56 Atanassov, supra note 2, at 2. 11 keeping domestic corporations incorporated and operating in the state.57 In addition, state antitakeover statutes provide further defenses for corporate management to resist takeovers.58 Today, most states have some type of law regulating takeovers,59 and ninety percent of American corporate capital is protected by state antitakeover statutes.60 As such, antitakeover law is one of the most heavily debated and litigated areas in corporate law.61 See the graph below for worldwide, announced merger and acquisition activity over the past three decades.62 57 David J. Marchitelli, Annotation, Construction and Application of State Antitakeover Statutes, 37 A.L.R. 6th 1 (2008). 58 John C. Anjier, Anti-Takeover Statutes, Shareholders, Stakeholders and Risk, 51 LA. L. REV. 561, 568 (1991). 59 California and Texas, which have not enacted antitakeover laws, are the major exceptions. Roy Harris, States of Grace: The State with the Toughest Antitakeover Statutes? It’s not Delaware., CFO, July 1 2002, http://www.cfo.com/article.cfm/3005340/1/c_3046525. 60 Id. 61 Michal Barzuza, The State of State Antitakeover Law, 95 VA. L. REV. 1973, 1975 (2009). 62 INST. OF MERGERS ACQUISITIONS AND ALLIANCES (May 16, 2013), http://imaainstitute.org/statistics-mergers-acquisitions.html#MergersAcquisitions_Worldwide (follow the *Worldwide* hyperlink found under “number and value of announced M&A transactions” heading). 12 State regulation of hostile takeovers suffered a setback in 1982 when the Supreme Court struck down a state antitakeover statute as unconstitutional under the Commerce Clause, reasoning that the statute imposed a substantial burden on interstate commerce that outweighed the interests the statute sought to protect.63 States responded by enacting several different types of antitakeover statutes intended to survive constitutional scrutiny—the two main types of which are control share acquisition statutes and business combination statutes.64 Control share acquisition statutes generally regulate the initial acquisition of shares by the bidder by requiring that the bidder obtain prior approval of current target stockholders before the purchases are allowed.65 Business combination statutes, on the other hand, limit the bidder’s ability to complete the second step of a transaction by preventing business agreements between the target company and the bidder for a certain time period.66 Delaware Antitakeover Law Because half of all publicly held companies are incorporated in Delaware, Delaware’s antitakeover statute is by far the most important antitakeover law in the United States.67 The Delaware statute, a business combination statute, prevents a bidder who acquires more than fifteen percent of a target company’s stock from completing a hostile takeover for a period of three years unless: (1) the board of directors approved the takeover prior to the transaction; (2) the bidder purchased at least eight-five percent of the target company’s stock in a single transaction; or (3) the target company’s board of directors and holders of two-thirds of the outstanding shares approve the takeover at or after the transaction.68 These exceptions make the Delaware law less onerous than antitakeover laws adopted by other states.69 Thirty-two other states have adopted business combination statutes that are comparable to the Delaware statute.70 Most of these other statutes are just as or more 63 Edgar v. MITE Corp., 457 U.S. 624, 643–45 (1982). See Marchitelli, supra note 57. 65 PATRICK A. GAUGHAN, MERGERS, ACQUISITIONS, AND CORPORATE RESTRUCTURINGS 97 (5th ed. 2010). 66 Id. 67 Id. (“[T]he debate over antitakeover law has tended to focus almost exclusively on Delaware law.”); Guhan Subramanian et. al., Is Delaware's Antitakeover Statute Unconstitutional? Evidence from 1988-2008, 65 BUS. LAW. 685, 686 & n.1 (2010) (“Delaware corporations comprise 51% by number and 61% by market capitalization of all U.S. public companies.”). 68 DEL. CODE ANN. TIT. 8, § 203(a) (2001 & Supp. 2008). 69 See Lucian Arye Bebchuk & Alma Cohen, Firms’ Decisions Where to Incorporate, 46 J. L. & ECON. 383, 406 (2003). 70 Subramanian et al., supra note 67, at 688. 64 13 powerful than the Delaware statute.71 The Delaware statute is a relatively mild version of the business combination statute.72 For example, the Delaware statute does not apply to a bidder that purchased eighty-five percent of the target company’s shares in a single transaction, and the statute’s three-year prohibition period on business combinations is shorter compared to those of other states, such as New York’s five-year limitation period.73 While courts apply the highly deferential business judgment rule when reviewing corporate management’s conduct in running the day-to-day affairs of the company, Delaware courts impose heightened fiduciary duties on directors in takeover situations.74 For instance, when directors receive a hostile bid and use defensive tactics to remain independent, Delaware courts apply the Unocal standard.75 The Unocal standard ensures that the directors’ defensive tactics are reasonable in relation to their belief regarding the danger of the takeover to the corporate policies and proportionate to the magnitude of the perceived threat to the corporate policies.76 Therefore, it may be more difficult for directors of Delaware corporations to resist a takeover attempt. Furthermore, while many states have adopted laws that allow the use of poison pills, a particularly potent defensive tactic, Delaware courts allow directors only to make limited use of the poison pill either to get a better offer for shareholders or to suggest a superior alternative plan.77 The Unocal standard is not the only standard Delaware courts apply in hostile takeover situations. There are two others triggered by different actions of the board of directors of the target company.78 The first came about in case familiar to any law student who as taken a mergers and acquisitions course, Revlon, Inc. v. MacAndrews & Forbes Holdings, Inc.79 The Revlon standard is a higher standard than the Unocal standard, and it applies when a target’s board of directors tries “to avoid the bid by selling to a friendly buyer or a ‘white knight’. . . .” When the Revlon standard is triggered, “Delaware courts [hold] that managers should not be allowed to prefer a lower bid to a higher one by reasoning that the lower bid arguably has better long-term prospects. Rather, they should simply pick the highest bid for the shareholders.”80 The last standard applicable to hostile takeovers, the Blasius standard, is even more strenuous. Delaware courts apply the Blasius standard, created in Blasius Indus., Inc. v. Atlas 71 Id. Roberta Romano, The Need for Competition in International Securities Regulation, 2 THEORETICAL INQUIRIES L. 387, 531–33 (2001). 73 Compare DEL. CODE ANN. TIT. 8, § 203(a) (2001 & Supp. 2008) with N.Y. BUS. CORP. LAW § 912 (McKinney 1998). 74 Barzuza, supra note 61. 75 Barzuza, supra note 61, at 1980–81. 76 Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co., 493 A.2d 946, 955 (Del. 1985). 77 City Capital Assocs. v. Interco Inc., 551 A.2d 787, 798 (Del. Ch. 1988). 78 See Barzuza, supra note 61, at 1980–81. 79 506 A.2d 173, (Del. 1986). 80 Barzuza, supra note 61, at 86. 72 14 Corp.81 when a target’s board of directors attempts to defend the target from takeover by interfering with shareholder voting rights “to circumvent the hostile bidder's attempt to use the proxy machinery.”82 When Delaware courts invoke the Blasius standard they “require [the target’s board of directors] to meet an almost impossible standard. In particular, they have to convince the court that there was a compelling justification for preventing shareholders from exercising their voting rights.” Most other jurisdictions take a more lenient approach when evaluating the legality of a target’s use of defensive tactics. Antitakeover Law Everywhere Else The antitakeover statutes of Maryland,83 Indiana,84 North Carolina,85 Ohio,86 Pennsylvania,87 and Virginia88 reject the heightened fiduciary standards imposed on directors in takeover situations established under Delaware case law. Instead, these statutes help companies by applying the business judgment rule to the use of defensive tactics. That is, if directors act with care, decisions will not be second-guessed by judges, including decisions regarding takeovers. The North Carolina statute, for example, applies the business judgment rule stating that “duties of a director weighing a change-of-control situation shall not be any different, nor the standard of care any higher, than otherwise provided in this section.”89 Explicitly rejecting Delaware’s heightened fiduciary standards, the Indiana statute provides that “[c]ertain judicial decisions in Delaware and other jurisdictions . . . that impose a different or higher degree of scrutiny on actions taken by directors in response to a proposed acquisition of control of the corporation, are inconsistent with the proper application of the business judgment rule under this article.”90 The map below provides a visual of which states had antitakeover laws as of 200391: 81 564 A.2d 651, 655-56 (Del. Ch. 1988). Barzuza, supra note 61, at 1987. 83 MD. CODE ANN., CORPS. & ASS'NS § 2-405.1(d)(1), (f) (West 2007). 84 IND. CODE ANN. § 23-1-35-1(f) (West 1999). 85 N.C. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 55-8-30(d) (West 2000). 86 OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1701.59(C) (West 2004). 87 15 PA. CONS. STAT. ANN. § 1715(d) (West 1995). 88 VA. CODE ANN. § 13.1-727.1 (West 2007). 89 N.C. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 55-8-30(d) (West 2000). 90 IND. CODE ANN. § 23-1-35-1(f) (West 1999). 91 Theodore Bolema, Repeal Michigan’s Anti-Takeover Law, MACKINAC CENTER FOR PUB. POL’Y , (Aug. 4, 2003), http://www.mackinac.org/5576. 82 15 Twenty-seven states have enacted control share acquisition statutes.92 First enacted by Ohio in 1982, a control share acquisition statute typically allows a bidder to exercise his ability to vote shares acquired in a tender offer only after getting approval from a majority of disinterested shareholders.93 Put simply, control share acquisition statutes allow shareholders to vote on whether they want hostile bidders in control. These statutes are typically triggered by stock purchases beyond a threshold percentage of the outstanding stock set forth in the statutes, which vary among states.94 The Ohio statute, for example, requires bidders to win a majority approval before they can purchase shares beyond twenty percent.95 Now that a background has been provided regarding the state of antitakeover law and its relationship to corporate innovation has been discussed, the importance of having a system of corporate laws that facilitate innovation can be explained. Commentary on the Importance of Corporate Innovation While the authors of Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence provide an excellent analysis of the relationship between innovation and the state of the market for corporate takeovers, they do not suggest the appropriate structure 92 Roberta Romano, The States as a Laboratory: Legal Innovation and State Competition for Corporate Charters, 23 YALE J. ON REG. 209, 215 (2006). 93 Id. at 227. 94 Marchitelli, supra note 57. 95 See OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1701.01 (West 1999). 16 for the legal environment governing takeovers.96 Despite finding the two scenarios in which a manager’s incentives to innovate are maximized, Sapra and his coauthors say nothing regarding what level of innovation is optimal for the shareholder and by extension the economy.97 They also mention nothing about the relationship between corporate innovation and the economy on a macro scale.98 In this regard, Atanassov does marginally better in Do Hostile Takeovers Stifle Innovation? Evidence from Antitakeover Legislation and Corporate Patenting but not by much. Atanassov does, however, state fairly clearly that antitakeover laws stifle innovation so from that it can be assumed that he believes legislatures should strive to create legal environments that encourage optimal levels of innovation.99 Without innovation, the United States would be obliterated by its competitors. In the words of Jackie and Kevin Freiberg, “Innovation must become a collective mindset and effort. Everyone must look for and engage in innovations in their spaces of influence, to include product, service, cost, design, and efficiency innovations.”100 Innovation is Key to a Vital Economy United States legislatures should seek to enact legislation that will foster optimal levels of innovation because innovation is a catalyst for economic growth. If firms had not produced and strived to perfect gunpowder, the steam engine, the computer, and the now ubiquitous Internet, the proverbial economic pie would shrink to a sliver or at least become vastly smaller than it is today. None of these economic growth catalysts would have come to be without innovation. Having said that, unchecked levels of careless innovation could lead to disaster. An easily imagined, but perhaps farfetched, example of this is the scenario where humanity destroys itself with its own weapons. The atomic bomb is as much a product of innovation as antibiotics. Therefore, the pertinent questions are what level of innovation is economically optimal, and what must be done to create a legal environment that fosters an optimal level of innovation? A unique era of human history is being embarked upon. The way innovation takes place in Western societies is changing, and companies are primed to make technological advances like never before.101 “The [innovation] revolution spurred by venture capitalists decades ago has created the conditions in which scale enables big companies to stop shackling innovation and start unleashing it.”102 Because of new technologies, specifically technologies that facilitate cheap, instantaneous sharing of 96 See generally SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1. Michael Abramowicz, Speeding Up the Crawl to the Top, 20 Yale J. on Reg. 139, 145 (2003). 98 Id. 99 Atanassov, supra note 2, at 2. 100 Jackie Freiberg & Kevin Freiberg, Innovation Vertigo What, Where, When and How?, Leadership Excellence, May 2013, at 15. 101 Scott D. Anthony, The New Corporate Garage, Harv. Bus. Rev., Sept. 2012, at 45. 102 Id. 97 17 information, combined with the globalization phenomenon have catapulted the business world into an arena where only firms able to innovate at breathtaking speeds will survive.103 Current examples of relevant corporate level innovation include: Medtronics Healthy Heart which is a program by Medtronic (“the world’s largest stand-alone medical device manufacturer”) to help rural Indians gain access to heart healthcare through a businesss model innovation;104 Unilever’s “Purelt, a portable water purification system [that] provides safe water at half a cent per liter;”105 Syngenta’s “Uwezo crop-protection chemicals and seeds [which] use the [innovative] sachet distribution model plus supportive education and training to drive adoption by smallholders;”106 and IBM’s plan to build smarter cities which “bundles technology and related services to help cities efficiently manage energy, water, traffic, parking, public transit, and crime.”107 In light of these examples of corporate innovation, it becomes easy to see that corporate innovation is not just important because of the way it impacts the United States economy. Many people’s quality of life around the world benefit from the innovations of corporations. For example, if a pharmaceutical company innovates in a way that makes a previously unaffordable drug affordable to the citizens of a third-world country, then the people who can now afford the drug have a much better chance to be healthy. It is through this lens that state legislatures must look when they decide whether they will actively pursue the enactment of legislation that will strive to optimize innovation. In the past, corporate law scholars have referred to the evolution of corporate law as a “race to the bottom.”108 Others have argued conversely that it is a “race to the top.”109 It could be argued that without innovation there could be not improvement.110 Without improvement, corporate law would be stagnant or worse; it truly would be a race to the bottom. A legal environment that fosters an optimal level of innovation by either encouraging or discouraging corporate takeovers is more in line with the “race to the top” ideology than is a legal environment that minimizes innovation. 103 Id. Id. at 47. 105 Id. at 49 (noting that “[m]illions of units have been sold throughout India. The goal is to provide clean water to 500 million people”). 106 Id. at 49. 107 Id. at 49 (noting that “[a] Stockholm project reduced carbon emissions by 17% and traffic delays by 50%. Projects have been completed in at least seven other cities”). 108 William L. Cary, Federalism and Corporate Law: Reflections Upon Delaware, 83 YALE L.J. 663, 666 (1974). 109 Ralph K. Winter, Jr., State Law, Shareholder Protection, and the Theory of the Corporation, 6 J. LEGAL STUD. 251 (1977). 110 Even in the case where a person is practicing to make become better at something she already knows how to do, it can argued that practice without innovation will do her absolutely no good. If she does the same thing exactly the same way every time, she cannot improve. 104 18 If corporate law is going to foster an environment in which mergers and acquisitions are a significant driver behind corporate innovation, the corporate law itself must change. Shareholders, and by extension citizens of the United States, should favor change of the corporate law in this direction.111 Many scholars believe that competition among the states to develop the most desirable corporate law structure for companies to enjoy will facilitate the race to the top. In his article published in the Yale Journal on Regulation titled Speeding up the Crawl to the Top, Michael Abramowicz notes that prominent law and economics scholars believe: [S]elf-interested entrepreneurs and managers, just like other investors, are driven to find the devices most likely to maximize net profits. If they do not, they pay for their mistakes because they receive lower prices for corporate paper. Any one firm may deviate from the optimal measures. Over tens of years and thousands of firms, though, tendencies emerge. The firms and managers that make the choices investors prefer will prosper relative to others.112 State legislatures should not make it more difficult for managers to optimize innovation. They should do their best to not be reactive but proactive in enacting takeover laws. The results are in and Sapra and his coauthors as well as Atanassov have found that, at the very least, innovation is stifled in the face of lukewarm antitakeover laws. While it is true Sapra and his coauthors found that innovation is maximized when takeovers are entirely prohibited, it would not be possible or practicable, for a myriad of reasons, for legislatures to eliminate takeovers. Instead, the legislatures should legislate laws that would create a legal environment that optimally balances innovation concerns against the concerns of hostile acquirers running roughshod over unwilling targets. This legal environment most likely falls somewhere to the left of the minimum of the U-shaped relationship predicted by Sapra and his coauthors and the far left of the U where innovation is maximized. Without innovation there is stagnation. Stagnation is very bad for corporations, especially in today’s hyper-competitive, global market place. Encouraging and fostering innovation should be a top priority for any United States legislature, federal or state, that is considering enacting laws that affect the corporate landscape and specifically, the legal environment in which mergers and acquisitions take place. Otherwise, the United States will face significant hardships as the global economy marches on without it. Conclusion Mergers and acquisitions are an enormously important part of the corporate law landscape. In addition, they are one of the most significant drivers of corporate 111 See Abramowicz, supra note 97, at 145. Id. at 140—41 (citing FRANK H. EASTERBROOK & DANIEL R. FISCHEL, THE ECONOMIC STRUCTURE OF CORPORATE LAW 6 (1991)). 112 19 innovation. The ability for corporations to innovate is critically important in any economy and especially so in the global economy. Haresh Sapra, Ajay Subramanian, and Krishamurthy V. Subramanian undertook to analyze the relationship between external takeover pressure and corporate innovation. In their report Corporate Governance and Innovation: Theory and Evidence, they theorize that “Innovation is fostered either by an unhindered market for corporate control, or by anti-takeover laws that are severe enough to effectively deter takeovers.”113 Another scholar researching the same field, Julian Atanassov, concludes that the states stifle innovation when they enact antitakeover laws.114 While at first these two theories seem to be at odds with each other, they can be harmonized. The theories are not inconsistent if Atanassov’s analysis is seen as a subset of the analysis of Sapra and his coauthors. The current state of antitakeover laws in the United States is summarized above. It is safe to say that most jurisdictions have an antitakeover statute or at least some form of law that impedes corporations trying to acquire unwilling targets. It is of paramount importance that legislatures attempt to optimize innovation as opposed to other goals such as appeasing special interests when enacting legislation that affects mergers. Corporate innovation has made the quality of life of the average human exponentially better. It is critically important to the success of the United States economy. United States legislatures, state and federal, should only enact laws they believe will help them win what should be the “race to the top.” Enacting laws that optimize innovation should be an ever present goal of United States legislatures. 113 114 SAPRA ET AL., supra note 1. Atanassov, supra note 2, at 2. 20